“It could be said that teaching is Norbert’s artistic practice” Janine Burke

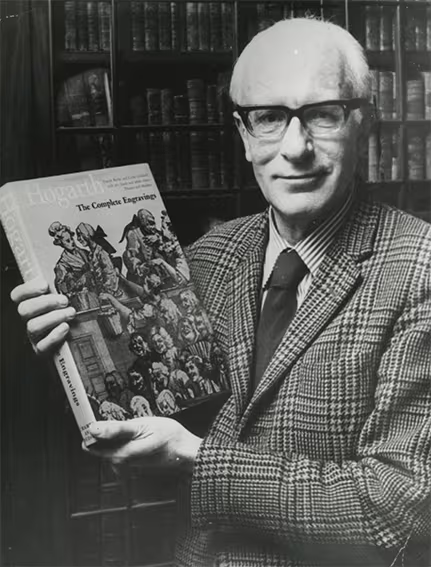

Back on 3 May 2025, the day of voting in the federal election, Prahran lecturer Norbert Loeffler, who is fondly remembered by many alumni, particularly those from the 1980s cohorts, spoke to a large audience at the Museum of Australian Photography as part of The Basement lecture series.

He sketched out little-known aspects of his life and career, but modestly, and admitted that he had strayed from his theme ‘Teaching art history at Prahran, with Norbert Loeffler,’ providing instead an express tour of the art scene of the 1970s and its international contexts. Passages from his nearly 90-minute, 9,000 word address at MAPh are interwoven here, and the full transcript can be read at the bottom of this post.

Norbert was born in 1946 in Germany and, in Australia, established himself as a lecturer and commentator on art history and theory. His capacity for original thinking and persuasive argument—delivered usually without notes—left his students awe-struck. His career as a lecturer may be said to have begun in the mid-1970s at Prahran College of Advanced Education, though it germinated in the 1960s, and even today, in his late seventies he continues to lecture at its successor, the Victorian College of the Arts, now part of Melbourne University.

As he tells it:

“…my life story is complicated: very briefly, I was born [in 1946] in East Germany, under Soviet occupation, then moved to Hamburg in West Germany, where my mother came from. She was a single mother at that stage. I grew up there and my first 2 years of school were at a wonderful modern Steiner Waldschule where my interest in art of all kinds began early by the age of 8 years. Then followed migration [1955] with its interruption to my education; my mother, for some extraordinary reason—she could never explain why—organised an application to come to Australia, which was fairly lucky because we could have ended up in Chile or South Africa, which would have been far worse; look at the respective histories of those countries!

“We ended up in Australia, at the outer reaches of the western suburbs, in a half-house, very small, in the middle of a paddock, unmade roads, no sewage, where the immigrants in the mid 50s ended up in large numbers, and of course, they were allocated jobs in the local factories, the factories that 10, 20 years later would disappear. So there we were…in those days, it was the early beginnings, and it was poverty for some of the Australians living there, it was poverty for the immigrants, and the immigrants came from many countries; West Germany, or from Italy, Greece, they came as refugees, out of Eastern Europe, fleeing the Soviet invasion of Hungary in ’56, or of Prague in ’68, or they were slave labourers in concentration camps during the second World War and they couldn’t go back where they came from, because the Soviets occupyed their countries.

“So there was a desperate attempt to produce schools for the huge numbers of immigrants coming into these marginal areas, but they could never keep up with the demand. When I went to high school, the school was unbuilt, lacked furniture, lacked enough rooms; we had classes in the shelter sheds, classes in a little tin shed or the Nissen hut down the road and, of course, of the people who began in the school, about 120 in first form, only about eight managed to get to tertiary education. The others ended up in a factory, or in an office. The school was a problem, it wasn’t a fault of the teachers, it was the fault of the system that couldn’t keep up with demand; there was also an extreme shortage of teachers. I spent too many miserable years in regular

Former teacher Bruce Alcorn, for the St Albans High School ‘Silver Jubilee’ writes that in the second year of the school, “our new 1957 Form 1 intake produced some very interesting students…easily the most academic-minded students one would wish to have in a school. Amongst the boys were Norbert Loeffler, Julian Castagna [who became a filmmaker/winemaker], Ian Sharp, Per Becker, Joe Darul, and Les Cameron, all first-class lads in their own individual ways.”

Norbert however, found the school disappointing:

“The problem I had, is that I was interested in art, interested in reading. Nobody else in my family, nobody else around me, none of my friends, nobody else was interested. I don’t know why I was interested. The poor education, financial need, and given problems with one of the other members of the family, I thought my education was going nowhere. Whatever leads I had to being a writer or architect or whatever went out the window. In these schools I learnt not to allow education to interrupt my interest in knowledge, so I became an ‘autodidact’ at an early age.

I abandoned high school in fourth form—better to get a job offering a small salary and giving me freedom than being stuck sitting in a classroom being bored, learning nothing. In other words, I didn’t need education. I needed to learn. I worked in a bank, retail, various factories, and for a year as wharf labourer – all the work was easy and gave me time and money to learn and be involved in the increasing cultural events in Melbourne.

“Dull as Melbourne was about 1960, there was still a fair bit to offer, and I started to regularly go to the city and search for galleries, bookshops, and you could find them bit by bit, for example, I saw The Family of Man in 1959, I saw it two or three times…there was nobody else, from memory, in the room.

“There was the Melbourne University Film Society, the annual Melbourne Film Festival with huge crowds, the Carlton Film Co-op, the new small cinemas screening the latest films from France, Sweden, Japan, etc., the new Melbourne Theatre Co., followed by La Mama, the Pram Factory, the opening of the new NGV and The Field show, Strine, Tolarno, Pinacotheca Galleries, and the new bookshops with the books of Sartre, de Beauvoir, Fanon, Arendt, Sontag, Greenberg, Lippard … I moved to Carlton c. 1965 and became involved with all the above. I also applied for a junior position at the ABC several times without a response.”

Like many of the students he was to teach at Prahran he had lived in the western suburbs and…

…finally, in 1969 I deliberately returned to the problematic high school in the “Wild West” that I had earlier abandoned, to study and gain entrance to a university. My experience and knowledge at this time had me appointed to various leadership positions, used as a part-time teacher, and be the full-time art teacher of the senior art class.”

Coincidentally, Prahran alumna Sandra Graham was posted to St Albans High School in 1968, contemporary with Norbert’s return to study there: “I worked with the staff in Norbert’s photo below. Alison Glidden, John Mc Inerney and Arnold Shaw. I don’t remember meeting Norbert back then as I was mainly involved with the junior year levels, but the magazine Alba I do remember.”

A penchant for argumentative writing emerges from these final years of Norbert’s study at St. Albans High School which qualified his entry into Melbourne University. His experiences in the school and in the outer suburbs radicalised him. In 1968 and 1969 Loeffler was editor, beside Monica Reish, Stephen Skok and Mary Axiak, of alba, the school’s magazine. In it is a persuasive article ‘Inequality In Education: Do Parents Care?’ and though it is uncredited, what follows in Loeffler’s career makes it patently clear he must have been its author.

Norbert’s article argues that the education system fails children from poorer areas like St Albans and he covered the circumstances in more detail in his lecture at MAPh. Schools in such working-class suburbs, he writes in alba, suffer from overcrowding, understaffing, and inadequate resources, while wealthier areas benefit from better facilities, greater government funding and an ability to raise more money. The disparity in university admissions provides concrete evidence of disadvantage: only 1 in 21 children of unskilled or semi-skilled workers enter tertiary education, compared to 1 in 3 children of professionals. Furthermore, poorer students are more likely to drop out due to a lack of qualified teachers and academic support (another article, possibly also by Norbert, identifies the rare teachers at St Albans High who remained longer than 5 years). In conclusion he asks:

“Should not a more equal economic assistance be given to the students who have social disadvantages to keep them at school? Should they not have equal schools, instead of the worst? Should they not have teachers who are specially trained to help them overcome these disadvantages and problems?

He remembers:

“…the senior students led by me joined a national campaign organised by the National Union of Students on inequality in Education – we held street-corner meetings, gave speeches, and distributed thousands of pamphlets (supplied by the Melbourne University SRC), across the Western Suburbs publicising the lack of funding and disadvantages suffered by local students.

“At the start of the next year at Melbourne University(1970), I had a meeting, previously arranged, with the Education Vice-President of the SRC who wanted me to informally take over his role and then work formally after the next student election. I agreed and education projects became my main work for the next years, rather than the academic course.

“The SRC now pushed to improve the content of courses, teaching and assessment, and set-up staff/student committees to continue this. The SRC also joined the 3 Teacher Unions and the Parents Organisation of Public Schools to campaign for education reform in state and federal elections. I also accepted a 1 day a week research position for a year with the Parents of Public Schools organisation to develop their policies and to produce a study on the “Cost of Free Education” – the compulsory fees charged for excursions or art materials.”

The Bulletin of 29 Jan 1972 carries an article ‘Education: Fighting Inequalities’ by Elisabeth Wynhausen that echoes Norbert’s arguments in the school magazine and records his active solution to the problem of inequality in education:

“Botticelli’s Birth of Venus slid onto the wall for a few moments, then a slide of a contemporary painting, stark white with straying pastel lines at the sides, replaced it. Students, overawed at first, responded to the contrast with an animated discussion…There are 250 students from inner and western Melbourne suburbs at the “matriculation summer school” organised by some members of Melbourne University’s Students’ Representative Council [in] a unique attempt to improve the educational prospects of children at schools in the industrial and working class areas of the city. In such areas the lack of educational facilities at school is almost invariably matched by sparse cultural and educational resources in the home…

“The project was initiated by Norbert Loeffler, SRC Education vice-president, who went to St. Albans, one of the schools invited to send students. “We are shocked at the appalling physical conditions and lack of staff in these schools,” says Mr. Loeffler. “Students in these schools often don’t stand a chance: in 1970 only 21 percent of the sixth form students at Princes’ Hill High School, Carlton, passed matriculation; this compares with about 80 to 90 percent in many private schools and 60 to 70 percent in most high schools in southern and eastern suburbs.”

“At exclusive Wesley College, a few miles away, there is another summer school. Students are paying $30 per subject. Norbert Loeffler is scornful about it. “Where are inner suburban students supposed to get that sort of money—not from the government, that’s for sure.”

Norbert explains his contribution:

“I created the free SRC Summer School : a 2 week school each January that provided lectures and tutorials on key matriculation subjects by volunteer academics and university students for students from marginal/disadvantaged backgrounds, and regular lectures on key topics at the university during the year, plus individual tutors for some students – the Summer School continued for nearly 50 years – MU “suspended” it during the pandemic.

Later in 1972, Norbert was a member of another editorial board, on Dissent, a Radical Quarterly, founded by James Jupp and Peter Wertheim in 1961 and published until 1978, in co-operation with the SRC, University of Melbourne (a later Monash University journal of that title appeared in 2000). He joined other editors David Breton, Will Henderson, Greg Hocking (later founding director and conductor for Melbourne Opera), James McCaughey (from 1975 initiator of Drama, making Melbourne University the first Victorian university with theatre studies), Adrian Nye, Mary-Anne O’Connell, Marg. Pimblett, Larry Stillman, John Timlin, and his colleague on Melbourne University’s SRC, Sara Wisnia. Editors at other times included Vincent Buckley, Chris Wallace-Crabb, Denis Altman and John Playford and the journal saw itself as an independent commentator on political, social, economic and cultural issues. Ken Mansell in Student Radicalism Under Fire notes that:

The effect of ‘Vietnam’ as a radicalising issue was perhaps most clearly seen in the transformation of the journal Dissent which, at the outset, had reflected Cold War priorities. Until 1965, Dissent was edited by Leon Glezer and Peter Samuel, both originally closely associated with the anti-communist Melbourne University ALP Club. By the winter of 1965, defence of United States foreign policy was becoming increasingly difficult. Glezer eventually moved to a position critical of the U.S over Vietnam but Samuel remained unrepentant. In successive issues of the journal – through 1965-66 – Samuel engaged in a heated discussion over ‘Vietnam’ with Monash University Politics lecturer Graeme Duncan. Criticism of the carnage in Vietnam occupied increasingly greater space in Dissent. Within a period of less than two years the journal became a forum for the ‘New Left’.

Loeffler’s activities at Melbourne University extended to its accommodation of emerging Australian art:

Kiffy Rubbo, then Head of the Rowden White Library, and I “invented” the George Paton gallery and brought together the initial advisory committee, including artists from the Prahran and VCA art schools and art history students – see the recent 50 year anniversary exhibition. I was also involved in the Vietnam war demonstrations, feminist/homosexual rights protests, the campaign that finally had the young children of students accepted by the university creche, the production of Farrago newspaper, and much more.

As Janine Burke remembers it:

“Rubbo’s sense of community was intrinsic to her cultural vision. For example, in 1974 she initiated the Ewing Gallery Collective, inviting a range of artists including John Davis, Fred Cress and Paul Partos as well as curators, critics and art historians such as Grazia Gunn, Mary Eagle and Norbert Loeffler. Rubbo’s explanation was characteristically frank. ‘I have always felt intimidated by having the last say so I set up a gallery collective … and together we get the ideas going’.”

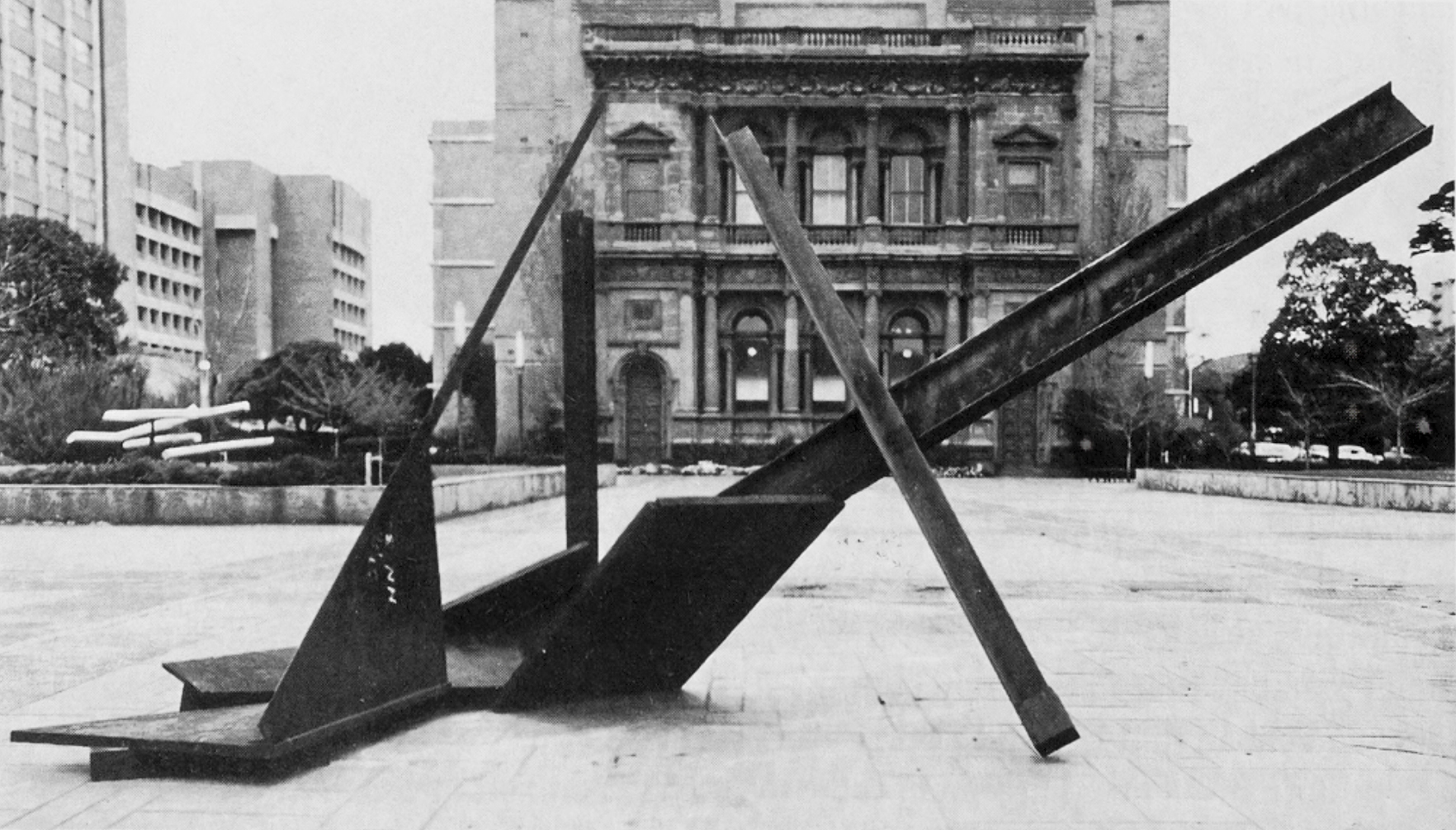

Norbert was no doubt instrumental in (unknown) Prahran photography students exhibiting in the Paton Gallery sometime in 1972, and Prahran painting/printmaking students including Howard Arkley showing Paces there 25 Sept.–13 Oct. 72, and with Rubbo and Meredith Rogers, Norbert wrote the catalogue for the Ewing Gallery Outdoor Sculpture Exhibition at the Ewing and George Paton Galleries of 1974.

Loffler quit at the end of the third year of his combined Literature and Art History (“English and Fine Arts”) honours course – “the quaint titles reveal something of the problem I had with the limitations of the course and institutional education.”

“The offer to create a new course of Art History and Theory for students of art at the Prahran CAE came a short time later; how I ended up there, it was was a surprise for me, and for them too, because the situation was, late in ’74, early ’75, that they decided, like other institutions were doing at that time, particularly art schools, ‘hey, we must have some kind of history/theory department!’ The days when students just sort of hung around the studio, got occasional advice from staff, and that was somehow sufficient in terms of knowledge, that was past. Looking back now, you can see quite clearly, that Prahran was one of the first institutions to get an art history/theory department, and others around the country quickly followed.

“Now the problem, though, if you want to have a history/theory department, how do you find a person who can teach it, when nobody has ever actually studied it! For example, I studied art history, but that was a very dull traditional course, it was sort of British art history, 1930s style, or at best 1950s style, but now it was 1975 and huge changes have happened in the art world in recent times.

[Had Norbert waited to attend Monash University he would have found there Patrick McCaughey, whose Harkness fellowship in New York had been supported, ironically, by Joseph Burke. McCaughey became foundation professor of Visual Arts at Monash University in 1972 where I remember his vehement lectures promoting Abstract Expressionism, Colour Field and Clement Greenberg.]

“So, they lacked the staff…they asked ‘who can we find in Melbourne, who could maybe do the produce a programme at short notice, and teach it?’ and the only one they came up with was me. So I was contacted, and I thought they wanted me to do free lectures, I didn’t realise it was a job, the job didn’t exist at the time in Australian art. But they explained it was an actual job, that you’d be paid. So, yeah, on the advice of some the staff, and I must mention, it wasn’t nepotism, but several of the staff, were friends of mine, simply, I had followed them around the Melbourne art world for the previous five, ten, years. They were young artists who graduated from art school, National Gallery School, which was the key art school, the only art school, with just a few dozen students, in a little corridor at the back of the building, that housed, the National Gallery, the Library, and the Museum, and the National Galley School

“For the first time at the National Gallery in Swanston Street there was a sign of something different; a photography show The Photographer’s Eye that came from New York, from the Museum Modern Art, put together by John Szarkowski, a great figure of the ‘60s, ‘70s at the Museum. He became the head of the photographic department, and started organising photographic exhibitions, giving them great emphasis in a way no photography show in any museum around the world had before, few of which had a photography department, including ours of course. Belatedly, when the National Gallery moved to St Kilda Road, they created the photography department but without photographs [laughter]. The Museum of Modern Art in New York was the first major institution that started to collect photographs in a serious way and saw them as something artistic. They started in 1930, long before anybody else.

“At Prahran they said to me ‘okay, we’ve got the major art apartments, printmaking, drawing, sculpture, painting, photography…can you put a program together? But also, oh, I beg your pardon, we also have a ceramics department, also graphic design and industrial design. Could you maybe do something on that too? Oh, and yes, we’ve got a Foundation Year course, that we’ve just started… another 90 students, and four classes a week, with these these younger students’—and surprise —’can you also teach matriculation art (studio and theory) to 30 students of various ages (18 to 60 years old) with little formal education?’ Prahran CAE had received a grant – the Whitlam government NEAT scheme – to recruit these students, and if they passed, they could continue into tertiary education. (a majority passed, their art works had to be done at home because there was no space, they brought their art to me to guide them). The new Fraser government abolished the scheme.”

I started with a limited lecture and tutorial program for the undergraduate students ranging from c.1800 to the 1970’s.

Further problems arose; there were very few slides, and few art books…

“…a student was hired to photograph 100’s of images from books/magazines, the library received a list of books to urgently buy – I held up books, made photocopies, to show students art works …”

In 1975 Norbert produced lectures and medium specific tutorials, but not for photography. At the end of 1975 he had saved enough for a 10 week tour of the US art scene – 5 weeks in New York and 5 weeks other key cities – Los Angeles, Chicago, Washington, Dallas, Houston (in the same year that the NGV photography curator Jennie Boddington made her overseas trip to purchase works).

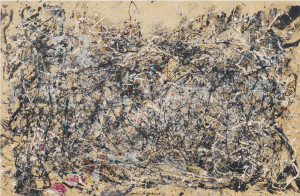

“…the first time I went overseas—able to flee Australia after 20 years when I thought they’d be locked up here forever—my first address, as soon as I got there, was the Museum of Modern Art…I was there half an hour early to spend the days at the Museum of Modern Art, because they had the major works; Guernica, Women of Avignon, and those huge works that the Americans were doing..if you wanted to see Pollock’s Number One, you have to go to the Museum of Modern Art… So there [also] was Guernica, on the wall, almost in an empty room!… in ’75 in New York just before mass tourism you could actually see these things, quietly sit there for lengthy periods of time and look…but you could also see them in relation to the earlier modernism of European art, for example, Monet’s great three-part Waterlillies, and similar works, and you could start to see a connection between the Waterlillies and, say, Rothko…”

“I returned with extensive experience of both old and new art, including photography, and books and slides.”

He joined the debate about the photography course…the 1976 ‘revolution’ as it was called by Paul Lambeth and Geoff Strong, then at the end of 1976 returned to NY for 5 weeks

“I saw Linda Nochlin’s pioneering Women Artists 1550-1950 in LA – one of many extraordinary exhibitions I saw in the next 4 decades in the US and Europe that influenced me … I also returned to Europe/Germany for the first time since 1955, and saw important art in Florence, Siena, Paris, Amsterdam, Hamburg, Berlin, Dresden, Munich, Vienna …”

Norbert’s teaching of history and theory to the photography diploma (and later, degree) students came about as Geoff Strong remembers in his 1988 essay ‘The Melbourne Movement: Fashion and Faction in the seventies’, the Victorian Centre for Photography’s The Thousand Mile Stare:

“The students felt the course was too imprecise and there was no understanding of the criteria used for assessment of their work (a common problem in art schools). They held a series of meetings, boycotted classes, printed manifestos criticising the course and even put on, in the guise of street theatre, a play lampooning the course for the benefit of in-coming first Years in 1977 [. . .] Athol Shmith, one of Australia’s most respected fashion photographers, who had been head of the department since 1972, took the students’ complaints very personally, but he did attempt some changes. Peter Turner, former Assistant Editor of the respected British magazine Creative Camera, came out from London for six months as guest lecturer. And for the first time in an Australian photographic school, photographic history, taught by Norbert Loeffler, was offered as part of the course.”

Prior to that, a few photography students took an art history elective, but it was John Cato, who provided photography-oriented content. His father Jack, with John’s assistance, wrote the first history of the medium in Australia; The Story of the Camera in Australia of 1955 (a facsimile edition was published by erstwhile Prahran photography lecturer Ian McKenzie and the Institute of Australian Photography in 1977). John’s knowledge of earlier Australian photographers was therefore excellent and he delivered several classes on them.

Of the course he taught to photography students Norbert says:

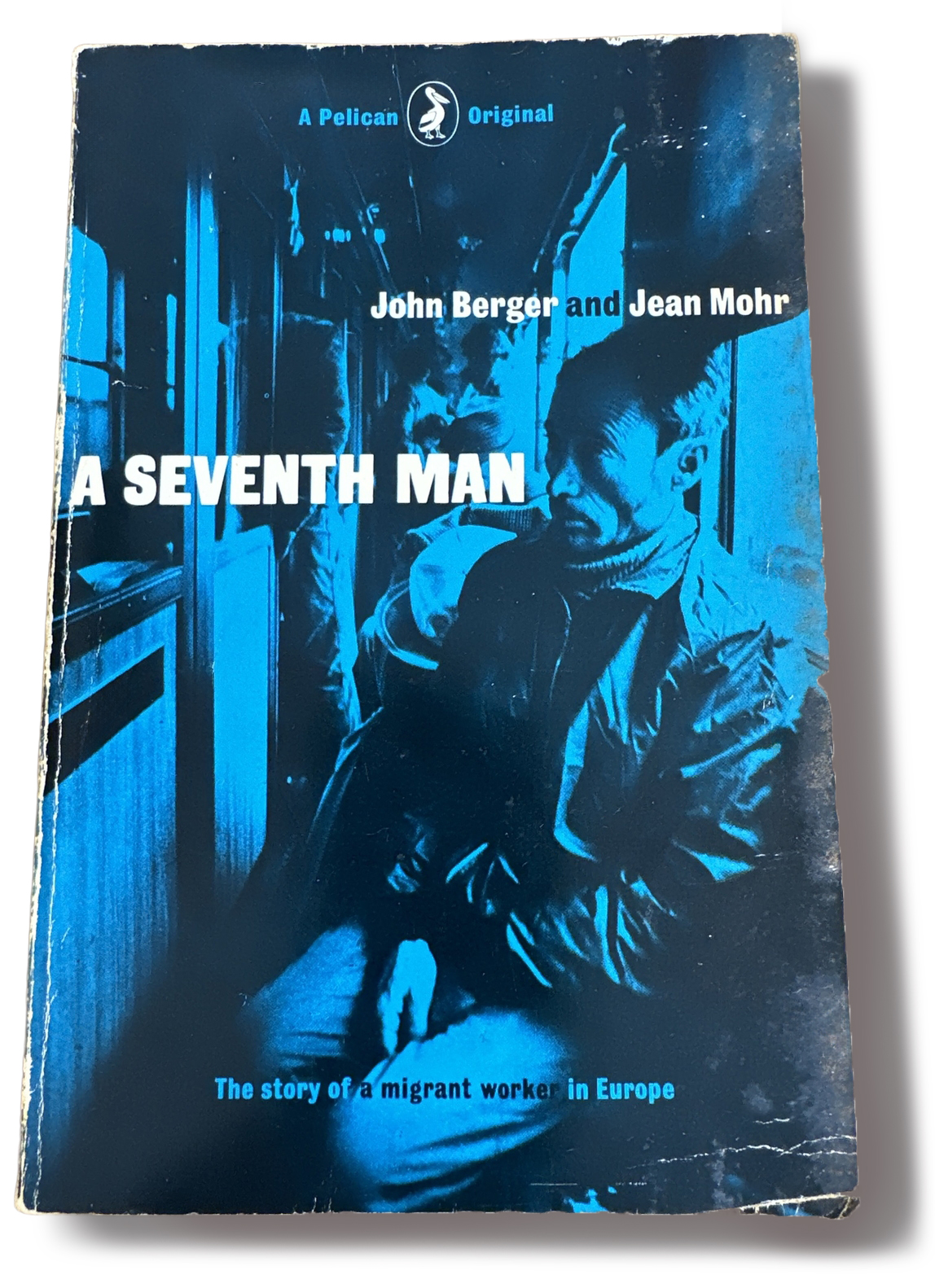

“Alas, I don’t have a detailed record of the photography theory course for 1976 – 78. My knowledge at this early stage came from The Family of Man, Wolfgang Sievers’ and Mark Strizic’s pictures of Melbourne, articles from German magazines Stern and Quick and books, Eugene Smith’s Minamata, John Berger’s and Jean Mohr’s A Seventh Man and other essays, war and Vietnam photos and the polemics around them, plus some knowledge of the history of Australian photography – Antoine Fauchery, J.W. Lindt, Nicholas Caire, Harold Cazneaux, Max Dupain … I also came across Alice Mills and other women who started photo studios in Australia.”

(Norbert is acknowledged by Barbara Hall and Jenni Mather in the catalogue for the George Paton exhibition Australian women Photographers 1890-1950 held 2-25 June 1981).

In 1977 Norbert had moved to bayside Hampton and had stopped teaching the Foundation Year students;

“I found a unique replacement in Tony Clark, who taught the students for the next decade, and eventually became an artist. At the end of 1977 I did not travel overseas because I planned to resign in mid 1978 and start postgraduate studies in Washington and NY, and possibly remain in the USA.

“In 1978/9 I gained much from the art in the USA but little from the course. I resigned (by habit) and flew to Europe to study art directly and learn more about the key art cities and countries.

“This time I also visited Barcelona, Madrid, Brussels, Prague … I finally stayed with friends in Munich for most of the year, working in their Greek/Russian icon gallery – an art form I admired and now could study : writing the “story” of icons, doing careful restoration work and two or three times a week looking after the new family baby.

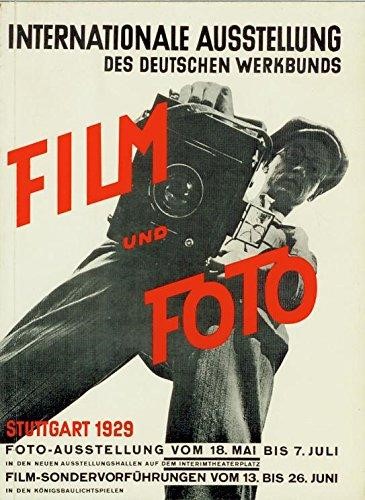

“Munich is a great art city : the famous Alte Pinakothek , the Neue Pinakothek, the contemporary Haus der Kunst, the former Degenerate Art Show Gallery, Lenbachhaus of Blue Rider (Kandinsky, Marc, Munter) fame, the Museum of Photography, Museum of Film, the Glyptothek (classical sculpture) – while in Munich I also went to Stuttgart to see the restaging of the legendary exhibition Film und Foto at Städtische Ausstellungshallen, Stuttgart, 18 May–7 July 7, 1929, arguably the most important photography show ever staged.”

It is difficult to discover writings by Loeffler, since most of his output is in the ephemeral form of the lecture, the traces of which can be glimpsed in the recorded presentations he gave at a variety of events both academic and public, the lecture notes and readings he produced for Melbourne University and in the fond memories of his students, for whom he was a phenomenon, a force for change.

Some insight into his wide-ranging contextual readings of art can be gained from 1978 essays, one appearing under Daniel Thomas‘s editorship and alongside Elwyn Lynn‘s text in the official exhibition catalogue Venice Biennale 1978: From Nature to Art, from Art to Nature, John Davis, Robert Owen, Ken Unsworth, (Sydney: Visual Arts Board, Australia Council, 1978) and in the elusive catalogue, Two Australian Artists at the Fourth Indian Triennial, for the Fourth Indian Triennial of Contemporary World Art.

Some insight into his wide-ranging contextual readings of art can be gained from 1978 essays, one appearing under Daniel Thomas‘s editorship and alongside Elwyn Lynn‘s text in the official exhibition catalogue Venice Biennale 1978: From Nature to Art, from Art to Nature, John Davis, Robert Owen, Ken Unsworth, (Sydney: Visual Arts Board, Australia Council, 1978) and in the elusive catalogue, Two Australian Artists at the Fourth Indian Triennial, for the Fourth Indian Triennial of Contemporary World Art.

Continuum and Transference, the installation that Davis presented in Venice was an arrangement of twigs tied together with cotton, partly covered with papier-mâché, calico cloth, latex, and bituminous paint. Norbert Loeffler referred to the belated discovery of Aboriginal art by an increasing number of local artists and that Aboriginal art had become one of Davis’s sources, as a celebration of natural cycles, though in 1985 Davis disavowed that in writing: ‘The work I make is formal and structured like a Western artist’s. It hasn’t got the feeling of myth and ritual that Aboriginal art has”. Loeffler also found in Davis’s work the representation of an experience akin to Patrick White’s solitary individual who experiences a spiritual epiphany in confronting the red heart of Australia (see Norbert Loeffler, ‘John Davis’, Venice Biennale 1978: From Nature to Art, from Art to Nature: Australia: John Davis, Robert Owen and Ken Unsworth, VAB, Australia Council, Sydney, 1978, np. Quoted in Naylor, ‘Australian contemporary visual arts from the outside in: a spatial analysis of Australia’s representation at the Venice Biennale 1954–2003, unpublished PhD thesis, Faculty of Art and Design, Monash University, 2007, p. 66.)

We find his contribution to a seminar ‘How do politics affect art’, at the Communist Party of Australia’s centre in Melbourne at 12 Exploration Lane.

With Prahran lecturers and other photographers he participated in an ABC television broadcast on 9 August 1979; Music Around Us: Silent Music with Norbert Loeffler, Athol Shmith, John Cato, Rennie Ellis and Max Dupain.

In 1980, Prahran Photography Department asked Norbert to present weekly photography classes…

“because not a single photography theory class had been presented in my absence (I also gave these classes from 1983 to 1990, as a VCA lecturer), then I was hired part-time by Prahran to assist the new art history lecturer to teach the course that I had created that they said ‘involved too many classes’.”

Through the 1980’s, he increasingly began to present many lectures and classes in other institutions:

“…the first ever lectures on photography and contemporary German art for the Art History department at Melbourne University ; lectures at other art schools/the National Gallery/Heide & Linden galleries/ photography schools/the CAE/secondary schools, etc.

In 1983, I was chosen to create a new comprehensive art history course at the VCA Art School comprising eleven lectures/tutorials/seminars a week for under- and post-graduate students. In 1990 the merger of the VCA and Prahran art schools created a larger school and course.

Janine Burke remembers:

“When I resigned from the VCA at the end of 1982 to pursue a career as a full-time writer and novelist, I was delighted that Norbert, an old friend and fellow alumnus of University of Melbourne, was appointed to the position, where he remains to this day. I can’t think of anyone more selflessly devoted to the education of art students. It could be said that teaching is Norbert’s artistic practice.”

Norbert continued giving community lectures; a Williamstown Community Outreach Centre file in the State Library contains a program schedule from 1981 for a series of lectures, gallery visits and lecture discussions on Australian art 1788-1981. Among the lecturers were Norbert, Ric McCracken, Alison Fraser, Jan Minchin, Sue Davis, and Peg McGuire. He wrote catalogue notes for Alun Leach-Jones’ works included in ‘The Collage Show’, 1982-83, funded by the Visual Arts Board Regional Development Program.

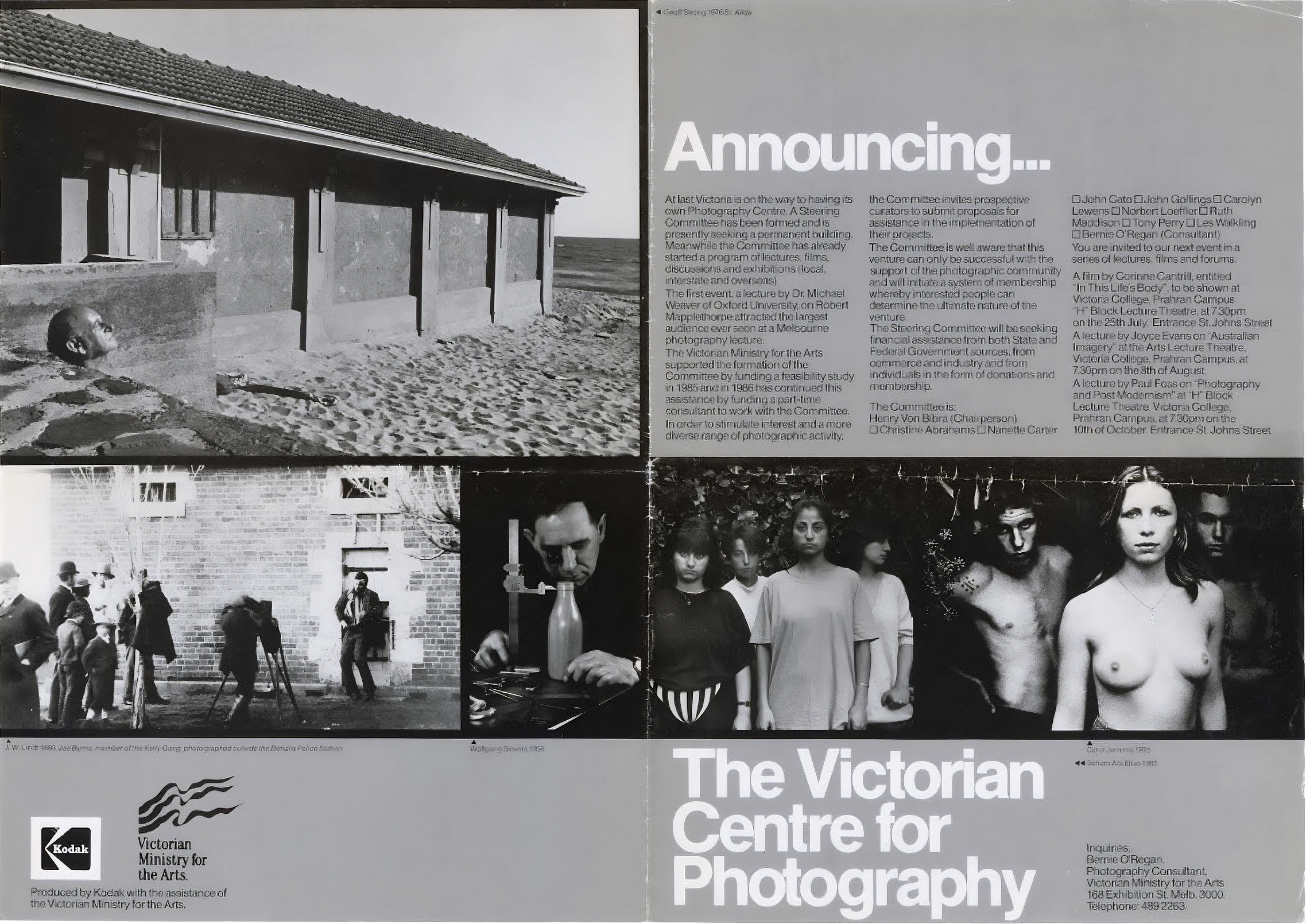

Crucially, for Australian photography, Norbert was among those who conceived of, and founded, The Victorian Centre for Photography. Members of the committee in 1986 that established what would later become the still extant Centre for Contemporary Photography were Norbert, and Bernie O’Regan, Henry Von Bibra, Christine Abrahams, Nanette Carter, John Cato, John Gollings, Carolyn Lewens, Ruth Maddison, Tony Perry, and Les Walkling.

The copy reads in part:

“At last Victoria is on the way to having its own Photography Centre. A Steering Committee has been formed and is presently seeking a permanent building. Meanwhile the Committee has already started a program of lectures, films, discussions and exhibitions (local, interstate and overseas).

“The Steering Committee will be seeking financial assistance from both State and Federal Government sources, from commerce and industry and from individuals in the form of donations and membership. The Committee is: Henry Von Bibra (Chairperson), Christine Abranams, Nanette Carter, John Cato, John Gollings, Carolyn Lewens, Norbert Loeffler, Ruth Maddison, Tony Perry, Les Walkling, Bernie O’Regan (Consultant)

“Invitation to their lectures, films and forums follows, all at Victoria College, Prahran Campus (i.e. Prahran College); A film by Corinne Cantrill, a lecture by Joyce Evans; a lecture by Paul Foss on ‘Photography and Post Modemism'”

With all of Norbert’s contributions to the Australian art world in this period and continuing since, it is his teaching that is remarkable to anyone who has experienced it. Of lecturing to tertiary art students, to photography students, he shares this insight:

You can’t teach them a way of making art, or the right subject matter. Each student has to work that out. You can teach a body of general knowledge, issues, and you can ask questions: why be an artist? why produce work? who do you produce it for? is there of meaning to it, or is it just some superficial escapism?

“I totally disagree with [a statement in The Basement book] that we somehow taught students mere self expression…we definitely didn’t, I definitely didn’t, it was always about questions, always about a challenge of what can one do, it wasn’t so much making beautiful prints necessarily… you might like beautiful prints, but it’s about something more substantial more profound that is in art, and also, of course, if you look at the key artists, you can see that its there in the photographs.

“The job of artists is to be an artist. There’s no job for artists that you can even go to when you finish art school! You start making work, and you can, of course, get part time work as a teacher, part time work by doing something, you know, helpful or documenting certain things, but the actual work that say a Bill Henson produces, or the work that a Rosemary Laing produces, or Tracey Moffatt produces—three of the most important Australian photographer of the last 50 years—is not of service to anybody. It’s speculative. It takes you to the point of the unknown to the point of where something disturbs you, it doesn’t give you answers, doesn’t give you a conclusion. Art doesn’t do that, art asks questions. The superficial banalities we get day by day given to us, here are… complicated.

“Tracey Moffatt’s got a very famous group we should look at; Something More one of the most important Australian photographic series ever produced. Something More. It doesn’t give you a conclusion…each of us, when we look at that work, would come out with different versions of what that work represents…it deliberately mixes things up. There’s no linear narrative; each photograph is ambiguous, there is no conclusion to the thing. “Something more”: there is more and more … beyond what we already know, beyond what already is registered or defined. Can you see, in terms of photography the art of photography, that’s the thing worth doing?”

Transcript of Norbert Loeffler’s presentation at the Museum of Australian Photography, 3 May 2025

Angela Connor introduced Norbert: I am absolutely thrilled, as I’m sure you all are, to be here today to welcome the remarkable Norbert Loeffler for Basement Lecture number four. Twenty years ago, I had the privilege of being taught by Norbert at the Victorian College of the Arts. His influence on me and on generations of artists across Australia, many of who are here in the audience is profound and enduring. Before I go on, I just want to get a bit of an indication from you—who was taught by Norbert in the in the audience here?

[most hands up]

Absolutely amazing. Norbert’s contribution to the Australian art world is unparalleled, in particular for The Basement, it was Norbert whom I turned to for historical information. His deep knowledge of the period and his generosity in sharing invaluable art historical insight shaped the direction of my essay for the publication (available for purchase $55).

[laughter]

Norbert began teaching at Prahran College in 1975, continuing through to 1978, and then returned to 1981. This was a time before the internet, before information was at our fingertips, yet Norbert found ways to bring the world to his students. He travelled overseas, collected books, took photographs, and returned to Melbourne with suitcases full of visual culture; materials that he shared freely with the students at Prahran. He helped open our eyes to the global art dialogue and placed us within it. To this day, Norbert Loeffler remains an educator and a thinker, whose impact is impossible to overstate. It is an honour to welcome him today….

[applause]

Norbert: My topic is the Prahran photographic department in the school of art. And how I ended up there, it was was a surprise for me, and for them too, because the situation was, late in ’74, early ’75, that they decided, like other institutions were doing at that time, particularly art schools, “Hey, we must have some kind of history/theory department!” The days when students just sort of hung around the studio, got occasional advice from staff, and that was somehow sufficient in terms of knowledge, that was past. Looking back now, you can see quite clearly, that Prahran was one of the first institutions to get an art history/theory department, and others around the country quickly followed.

Now the problem, though, if you want to have a history/theory department, how do you find a person who can teach it, when nobody has ever actually studied it? For example, I studied art history, but that was a very dull traditional course, it was sort of British art history, 1930s style, or at best 1950s style, but now it was 1975 and huge changes have happened in the art world in recent times.

At the end of World War II, in the 50s, Europe still believed that it was the centre of Western art, and then they got an awful of surprise; it was actually New York, increasingly, the main centre of art, and that realisation came as a terrible shock. The Venice Biennale in the early 1960s awarded the major artist award to an American cowboy—Robert Rauschenberg—and the European aesthetes, all protesting, said “the Americans have got good plumbing, but Europe’s got all the great culture. How can you give that [award] to somebody from Texas, you know—it’s the major gold award of key contemporary art at the Venice Biennale!”

What it set off—as you can imagine—what it changed!…you know Europe was in part in ruins; the effect of War II, and the mission of Europe, East and West, and European art schools, European culture in general, was fighting to recreate itself, particularly the major centres of European art. The Americans, in their abundance, they came out of War super rich, super powerful, the New American Empire. It’s no surprise that something that had been developing in New York was becoming the centre of Western art, and what everyone was predictably talking about, the so called New York school; artists like Pollock and others that were happily ignored until the ’50s, and then suddenly, they seemed to be the key new, younger artists of the world, and in numbers, and that was followed, of course, by things like Pop Art and other recent developments: the big American museums, because if you wanted to look at modern art, the new contemporary art, there was only one place where you could see it; New York. The Museum of Modern Art was the key institution. And then you had the other museums; Whitney, the Guggenheim, the Metropolitan, and a number of other museums and the private galleries. The new famous private galleries where those artists showed. And you had, after Lee Krasner, Pollock, Barnett Newman, you had the next generation, you have the pop artists and then various other more contemporary sort of artists of the late 60s and 1970s, and Europe was lagging behind.

The first sign of that was in Europe, in 1955, a major new art event was announced, the Documenta, which was in Germany. It was partly an effort to allow Germany, or West Germany, really, to pick up on where German art had stopped, with the takeover by the Nazis, because that takeover meant that the whole of the modern art tradition that had been realised in Germany was now shut down, completely. The artists had to flee, if you didn’t flee, you were murdered. The Bauhaus had to shut down as soon as the Nazis took over in 1933. And so, German modernist art, just stopped at that point. And of course, the artists ended up in places like New York, if they survived. So ’55 was an attempt to reconnect to what was lost, and also to catch up what had happened in the meantime… Picasso and others, their work of the 1930s that nobody had seen in Germany, or the New York work of the 50s and ’60s. And the sensation, of course, at the Documenta, in ’55, what particularly they were getting a look at for the first time was the new American art; Pollock and various others, that was a sign that something had greatly changed, a so called ‘paradigm change’, when the basis of art suddenly changes, causes bewilderment, ‘the shock of the new’, but also, it was a sign that something distinctly different had started back in America, and it probably had happened because of the input of the early European art that the Americans had accumulated, and nobody else in the world had done the same. Because where [did you go] if you wanted to see a major Picassos, major works of Matisse, major works of expressionism, major works of surrealism? Well, in New York, at the Museum of Modern Art.

For example, the first time I went overseas, I was able to flee Australia after 20 years, I thought I’d be locked up here forever, but I fled in ’75. My first address, as soon as I got there, was the Museum of Modern Art…I was there half an hour early to spend a day and repeatedly other days at the Museum of Modern Art, because they had so much of the major works; from Guernica, Women of Avignon, you know, all those works, particularly these huge works that now the Americans were doing. Yet if you wanted to see Pollock’s Number One, well, you have to go to the Museum of Modern Art. If you want to see [inaudible] you had to go to the Metropolitan to see it. But Guernica was there; at the end of the 1930s, in France, Guernica was sent to New York for safe-keeping. Picasso promised Guernica to Spain, but only if Spain got rid of fascism and Franco. So there was Guernica, on the wall, almost in an empty room! This was because the first time I got there in ’75 in New York was just before mass tourism. So you could actually see these things, quietly sit there, for lengthy periods of time and look at those works, but you can also see them in relation to the earlier modernism of European art. For example, Monet’s great three-part Waterlilies, and similar works. And you could start to see a connection between the Waterlilies and, say, Rothko, you know the big Rothkos and so on.

So anyway, this work, of course, is totally absent in Australia, because by 1970 or so nobody bought it until the sensation of the Blue Poles, when James Mollison trying to start a national collection, bought it for a gallery that had not been built or opened, the National Gallery, Canberra opened in ’82. The Pollock work that was here in Australia, here, caused a huge political rumpus, that was our first sign, and we had total bewilderment; on the one hand, the small group of people in the art world celebrated, and our mass media and the right wing in Australia went totally gaga, ‘painted by a drunk, how could Australia waste money on a Jackson Pollock. We all know he was mad…’ that kind of thing. It won the right wing an election in Australia in the early mid seventies!

But we can see from that this thing of trying to catch up, and trying to create a culture here that would have an understanding of the whole modernist tradition, which currently happened elsewhere, and we have little knowledge until Blue Poles arrived. None of those works had been seen here, except as small reproductions in art magazines or art books. And few people had travelled, didn’t have the money. Few artists had travelled, so also at my art history course at Melbourne University, oh, they never touched any of that, they didn’t have any classes on modern art, nothing on contemporary art, the staff knew nothing, and if you brought up photography, they would be totally bewildered…they never mentioned the word photography in the three years of the course. Ha…so the students of the art history department at Melbourne uni, the only one in Melbourne, of course, at the time, well, they were a bit useless, unless they wanted to be traditional art scholars, art history scholars, you know? Do research on some obscure drawing from the 17th century at the National Gallery…they’d be good for that, or a few of them would, but as for the rest, they have no knowledge of modern or contemporary art. You remember the life of Melbourne University is 1819, and ain’t been overseas. They’d very little access to modernist texts or literature of what had happened in the modernist tradition, which happened in Europe and then moved to the United States.

So, [Prahran] lacked the staff…they asked “Who can we find in Melbourne, who could maybe do the produce a programme at short notice, and teach it?” and the only one they came up with was me. So I got contacted, and I thought they wanted me to do free lectures, I didn’t realise it was a job, the job didn’t exist at the time in Australian art. But they explained it was an actual job, that you’d be paid. So, yeah, on the advice of some the staff, and I must mention, it wasn’t nepotism, but several of the staff, were friends of mine, simply, I had followed them around the Melbourne art world for the previous five, ten, years.

They were young artists who graduated from art school, National Gallery School, which was the key art school, the only art school, with just a few dozen students, in a little corridor at the back of the building, that housed, the National Gallery, the library, and the museum, and the National Galley School in the little corridor at the back alongside these three major institutions. And of course, yeah, there was little space.

For the first time at the National Gallery in Swanston Street there was a sign of something different, there was a photography show that came from New York, from the Museum modern art, put together by John Szarkowski. John Szarkowski was a great figure of the ‘60s, ‘70s at the Museum of Modern Art, he became the head of the photographic department, and he started organising photographic exhibitions in a major way, giving those exhibitions great emphasis in a way no photography show in any museum around the world had before. Most museums, major galleries around the world, had no photography department, including of course, belatedly when the National Gallery moved to St Kilda Road, they finally created the photography department but without photographs. [laughter] The Museum of Modern Art in New York was the first major institution that started to collect photographs in a serious way and saw them as something artistic. They started in 1930, long before anybody else.

So again, you know, at Prahran at the art school, they’ve then said to me “Okay, you know, we’ve got these six departments the major art apartments, printmaking, drawing, sculpture, painting, photography…can you put a program together? But also—oh, I beg your pardon—we also have got a ceramic department. We also have got graphic design and industrial design. Could you maybe do something on that too? I mean, oh, yes, we’ve got a foundation Year course, that we’ve just started… another 90 students, and four classes a week, with these these younger students?” The Foundation course was designed, if you pass, to lift you into the tertiary program, either for design or visual art.

It was a new kind of course that was part of the big change in around the country to suddenly have not only art schools, but to have a place for a huge increase of art students. Actually was a mistake by Canberra. They created these Colleges of Advanced Education, you know, they’d got mainly more practical courses to do with things that the university didn’t cover, that increasingly became important, because Australia was transforming into a new economy. For example, in the mid 60s, 50% of all workers, mostly male, worked in industry and manufacturing. Today, it’s 7%. Now it’s our manufacturing industry area, which was like a museum anyway, back in the ’60s or earlier, it’s just disappeared, a car factory thing, that sort of stuff, or they were American or Japanese anyway, but they’ve disappeared.

In other words, our economy, our workforce, is now in a sort of service industry, economy, totally different to what it used to be. You know, the little dirty factories that were like you know, sort of antique factories or museums, they’ve disappeared. I worked in a number of them in the ’60s and sometimes in the University holiday periods, and they really were archaic, the work practices were archaic, the abuse of the workers was archaic. For good reason, they’ve disappeared.

You can see that’s why we’ve got colleges of advanced education, and a huge extension in the universities; in the in the mid 50s, Melbourne University was the only university; 6,000 students, 5,000 males, 1,000 females. When I started belatedly at the age of 24 or so at Melbourne University in 1970, there was an announcement in orientation week; “Hey, the university’s now got 20,000 students” and there’s more women at the university than men for the first time. So you can see the transformation and also, you know, by 1970, Monash had 20,000 students and a new university La Trobe had just started. And we have the colleges of advanced education, not just one visual arts school, the National Gallery School, but we suddenly had Prahran, Caulfield…RMIT had become a more important art school, Phillip up near La Trobe University, another art school, Yallourn, another art school, Bendigo another art school, Geelong another art school, Warrnambool, another art school. We possibly had the most art schools of any city in the world overnight.

Of course, the government corrected their little problem at a later time. But we suddenly had over thousand arts students, and we had work for the first time in Australia for 100-150 lecturers, artists who would work in art schools, sculpture, painting, photography and so on, they had a regular income, an artist could suddenly even live by their work they could produce work, they had studios, you know, they had partners, and they could even afford children, and things like that was never really possible in the past. And you could see the sense of renewal, or it wasn’t renewal, it was really something new and almost explosive, that happened, and it started happening suddenly in the late ’60s.

Now, why? Oh, Australia by the late ‘ 60s, and in fairly quick time had been transformed. We imported hundreds of thousands of immigrants…it was “populate or perish”. That was the lesson of World War II, but also with the hundreds of thousands of immigrants here, Australia suddenly became of very young country, in terms of the age of the population. The transformation of the economy, Australia became wealthy. The cities started growing explosively. What you also had, of course, was, the knowledge revolution. You had to have a different form of learning. Culture became important, and the first time we realised it was in the Olympic Games. The Games bought international visitors here and made politicians aware; ‘look, if we invest in culture, maybe even tourists could come to Australia! We’re surrounded by a billion potential tourists.’ And of course, even from far distances of people could come, because suddenly there was jet travel at the end of the 1950s into the ’60s. It didn’t take 35 days to get here by boat, or six months by sailing boat, any longer. In other words, the tyranny of distance suddenly collapsed.

Also, of course, the new communication. We suddenly had television by the ’60s, practically everybody in Australia had a television set, and by the late ’60s, you could watch international television. The Beatles singing All You need is Love on TV screens world wide.

The isolation was gone. It wasn’t good enough to be a provincial artist or have a provincial art world. The art world now, if anything worthwhile was produced, it had to be as good as art anywhere in the world. You couldn’t hide and say, look, I live in a village and I only can do so much. I can only be provincial. That was an alibi in Australia for a long time. It wasn’t anybody’s fault, but it was our position at the end of the world, a small population pretending to be British, even though they weren’t British, you know, and pretty ignorant about culture. We didn’t need it. For example, I’ll give you another good example, I mentioned Venice a moment ago, the Venice Biennale, Australia actually was invited to participate in the Biennale, to send an artist over in ’55 and again in about ’58. And from memory, Arthur Boyd went over and one or two other artists. And then, the Menzies government cancelled our participation, according to Menzies’ government’s position on the arts was that we don’t need modern art. Much of it is “communistic” or they also use various derogatory terms; “We don’t want that. Australia needs a pastoral art forms , sheep under a golden sunset”, something like that. So participation in the Venice Biennale was cancelled.

The next time Australia participated in the Venice Biennale was in 1978. And the artist, with my catalogue notes, was John Davis, who was head of sculpture at Prahran. And John Davis, of course, became a major figure. You saw his retrospective, very unique, very unusual artist, who doesn’t imitate the international fashions, but he forged something absolutely unique to Australia, without any imitating of the indigenous artists.

Since then, of course, we’ve had representation every year until this year when, if you read the scandal, where [Khaled Sabsabi] was selected for the next Venice Biennale and then a week or two later, his selection was cancelled. You can see what happens when politics gets involved. This person selected happened to be from a Middle Eastern background, and in the midst of the political chicanery of which for months we had for the election. The appointment was cancelled. So the at next Biennale the Australian pavilion will be empty, because nobody from the Australian art world will take his place. It’s a bit of an embarrassment, but it’s back to the provincial position. “We’re different, and we don’t need this sort of rubbish from the other parts of the world”. But of course, it’s not true. You know, that artist should’ve been selected, but it’s probably not going to happen. There’s not going to be a change. But it’s also a bit of a lesson how when politics interferes and ignorance interferes, suddenly we seem to be back a few decades to, you know, an earlier stage of Australian history.

Now, also I would mention, another example, it’s much more hopeful—in 1969, extraordinary event happened here in Australia. It was organised with private support and that was Christo and his wife, Jeanne-Claude, arriving in Australia and creating an extraordinary work, at Little Bay in Sydney with the help of dozens of art students, they wrapped Little Bay. It’s an extraordinary work, I won’t try to explain it now, but you can look it up…extraordinary work, there for a couple of weeks, it was the first major international work that the Christos had produced, and it set them off on many other works, all over the world after that. But, that work made news everywhere around the world. It was a sign that suddenly, here, in Australia, extraordinary works can be produced, whether it’s a local or anybody else, and works that are artistically important or changed the nature of art. They are given to new environmental implications of the work where art and environmental concerns now became part of the art world, for adding a new language of art works that had not previously been seen. It opened up all kinds of possibilities; the idea of land art, environmental art, lean art, and so on, but these artists led the way in that development. It was one of the things that I again and again lectured about for 40 years by talking about how the artist in the ’60s became involved before most others even noticed something was dramatically going on with our environment.

I’ll mention something else, there was an extraordinary book published in the mid 60s. It was sort of a sleeper. It was published, with great difficulty, and then, gradually when it was published, people noticed, and the book really became the the first great environmental statement; a book called Silent Spring. You can hear the implications—Silent Spring—produced by a young scientist Rachel Carson. That book was dynamite. I remember reading it and my my world changed suddenly.

So, see the connection, the way ideas creative effort, realities as they change, produce new works. And of course, it’s the topic you want to teach in an art school…you don’t want to teach academic concerns, you want to teach what happens in the studio. Art school is about making work, not academic processes. And of course, in recent years there’s been a big battle, as art schools have got bigger and bigger, where the universities are taking over the art schools, but the universities saying, “Oh, they need more academic subjects. The fact that 70% of the course is allocated to making things is too much. They should do maybe 50% or 60%.”

They’re eating away at the idea of practice, creation, the studio, they want to increase, you know, something that the fools in a government not long ago came up with, that idea that students who go to university should be ‘job ready’, and when they finish their course, they should be able to quickly step into the job for the sake of of the economy. And tell me how a photographer’s going to do that, or how a painter’s going to do that, or somebody wants to wrap Little Bay…how they can do that? Can you see, there’s a type of contradiction between economic concerns and concerns of political power and what art or music, or concerns we’re involved with, where they matter, in what they are about, and that definition or that notion has to be kept in mind.

Now, let me get to the point of that…I was interviewed, and I said, okay, exactly what would you like me to teach? And they shrugged their shoulders and said, “We’ve got no idea..we hoped you’d come up with something.” The people who interviewed me, a couple of them, they had never studied art history, they hadn’t been overseas. If they had knowledge of any art works, they’d never seen them! They had no experience. They hadn’t been the Paris of Vienna or New York or any of the cities, Venice, or ancient Athens, where the work was produced, they’d no idea!

The tyranny of distance kind of came back in about the 1970s, nobody, or, a only small handful of people had been overseas, and if they went overseas, they briefly went over to London. If they went to France or Italy for a week, they couldn’t speak French or Italian. They spent a day at the Louvre, which is about 20 kilometres of art. So, of course, without knowledge of art history, without knowledge of the cities, the actual works, without being able to compare different works, the people here were hamstrung. But that also changed because by the 70s, artists increasingly were able to make short trips overseas.

Also, what you had is organised travel, one of the first things I did by the early ‘80s, I organised trips across Europe across the United States, the New York, Paris, Rome, Florence, Vienna, Berlin and so on for years. I’ve done 25 of those trips across the world, including to the Venice Biennale seven times, including to Perspecta five times. Prospecta always happens every 5 years, always in the same location in Germany. It is the key art event of the world, not just artists from Germany, but it brings artists from around the globe together, to Kassel, the city in Germany where the Documenta got started in ’55 on a small basis, gets presented and the Documenta for the last 25, 30 years has been a global Documenta; no longer just Western art in the foreground and the few Japanese in the back somewhere…that’s over…we’re now in a globalist situation. That’s why now in election campaigns, certain parties want to ban migration, or ban students from coming to Australia…really clever ideas. So you can see you know, the sort of connections that come in.

In terms of myself, very briefly, I was born in Germany in the east of Germany, under Soviet occupation. I ended up in Hamburg in West Germany, where my mother came from. She was a single mother at that stage, back in Hamburg where I grew up. And then, my mother, for some extraordinary reason, she could never explain why, organised an application to come to Australia, which was fairly lucky because you could have ended up in Chile or South Africa, which would have been far worse. Look at the history of those respective countries.

We ended up in Australia, and then we ended up at the end of the western suburbs, in a half house, very small, in the middle of a paddock, unmade roads, no sewage, where the immigrants in the mid 50s ended up in large numbers, and of course, they were allocated jobs in the local factories, the factories that 10, 20 years later would disappear. So we were there. And of course, the area massively has changed if you look at the western suburbs now, but in those days, it was the early beginnings, and it was poverty for some of the Australians living there, it was poverty for the immigrants, and the immigrants came from 30, 40 different countries…West Germany, or they came from Italy, Greece, they came as refugees, out of Eastern Europe, Hungary, the Soviet invasion of Hungary in ’56, or they came from Prague in ’68, or they were slave labourers in concentration camps during their second World War in Germany, and they couldn’t go back where they came from, because of the Soviets occupying their countries.

So it was was there, and of course, it was a desperate attempt to produce schools because we had huge numbers of immigrants coming in, ending up in these marginal areas and you needed schools, and they could never keep up with the demand for schools. And when I went to high school, the school was unbuilt, lacked furniture, lacked enough rooms, we had classes in the shelter sheds, classes in a little tin hut or Nissen hut down the road. And, of course, of the people who began in the school, about 120 in first form, about eight managed to get to tertiary education. The others ended up in a factory, or in an office at best here or there. So the school was a problem, it wasn’t a fault of the teachers, it was the fault of the system that couldn’t keep up with demand. There was also an extreme shortage of teachers. So you become a teacher, it’s about one year tertiary education, to help until the teacher training, increased sufficiently that you actually have people with some basic qualification in teaching. So it was difficult.

The problem I had, is that I was interested in art, interested in reading. Nobody else in my family, nobody else around me, none of my friends, nobody else was interested. I don’t know why I was interested. But I started being interested and interested in reading from about the age of six or so. And I consumed books, film, theatre, art, music, I had an extraordinarily need for it, because of the absence of it. Think of the contradiction; where there’s a huge need, that you find a huge desire. That was my thing.

So anyway, the education, given financial need, and given problems with my family with one of the other members of the family, I thought my education was going nowhere. Whatever leads I had to, you know, to being a writer or architect or whatever went out the window, and the community was totally sterile no library, the nearest library was five kilometres away, but lacked books. The area had nothing; it was just a few houses, a little shopping centre, nothing much else, and that was fairly typical. And some of that still goes on today, if you, look at recent events and ideas about inequality in education, how certain people miss out completely, and it’s our fault. It’s not their fault.

A few of my friends continued straight through to the University. They had parents who could help but I was one of the others who left. I decided I’d have to quit without finishing fourth form, which of course, everybody warned me said, ‘no don’t’, and I said, ‘no, I’m going’, because it’d be better to get a job offering a small salary and giving me freedom than being stuck sitting in a classroom being bored, learning nothing. In other words, I didn’t need education. I needed to learn, and notice that contradiction between education, mass education, that’s supposed to lead to jobs soon. Studying particular subjects, which often results in job training and nothing much else that we have as a system, and people actually want to learn, because our system stops people from learning. You make sure when you get good marks for VCE. That gets you into university and, more and more, university education is about jobs for the economy, ‘job ready’.

Now, I wasn’t interested in that, it’s like being Don Quixote and banging your head against a wall. But I’d got money from a boring job during the daytime and I had freedom in the evening. I’ve got access to books, I’ve got access to films, the theatre, I can go to that shining light in the distance called the city. Dull as Melbourne was about 1960, there was still a fair bit to offer, and I started to regularly go to the city and search for galleries, bookshops, and you could find them bit by bit, for example, I saw The Family of Man in 1959, I saw it two or three times…there was nobody else, from memory, in the room. The Family of Man show was seen by seven million people all over the world over six or seven years. It was produced by the Museum of Modern Art.

Now, The Family of Man show with its publicity, did wonders for photography because suddenly a that time photography was a major event. Photography was the key, mass medium, good or bad as photography is, photography can reach people everywhere, and from photography, of course, film comes, and from film, television came and so on. So can you see, suddenly photography seemed to be important, there was a huge audience for photography; we were in a new age of the picture. Photography, the consumer society, advertising, television, you know, you can go to a movie, once or twice a week, cheaply. Now you could watch 20, 30 hours of TV a week. Picture after picture after picture. They may not be good pictures or meaningful pictures, but you could watch it all. And look at the obsession now with iPhones and things like it. How images on the screen with backlighting, particularly once colour came, how it mesmerises people, and they can’t get the damn thing out of their hand even if it shows totally stupid, sterile, false things, they’re mesmerised by that glow and the repeated contacts that become possible. For example, the phone company will phone you ‘you haven’t phoned in the last few hours…make some phone calls’, and they’re happy, because they’ll make money from you.

Anyway, there I was and I started chasing around; seek and you will find. I found a few little jazz clubs, where you could hang out all night, with very strange bohemian and people—very impressive if you’re 15 years, 16 years old. In Melbourne, particularly, I found movie theatres that started to show the new internationally important films, the new French wave, the Swedish films Ingmar Bergman, the new Japanese films, who were Kurosawa, Ozu and so on; you could actually that in Melbourne. Melbourne University had a film society; I started turning up there, and they showed more films, and then, bit by bit I discovered things in Melbourne. By pure luck, serendipity, I moved moved into Carlton in ’65, ’66, so I started hanging around the university, but I was in Carlton. Carlton suddenly had a film co-op in the corridor where Brunetti is these days, it was the International Film Co-op and you could see the films of Yoko Ono, those extraordinary films that she made in the ‘60s, in Melbourne! Or short time later around the corner, the Pram Factory (1970) and shortly before, La Mama (1967). All happening while I was living 50 yards away in Faraday Street. And, of course, the new National Gallery had opened— I was at the opening…no invitation I just snuck in..what do I pay my taxes for? And the era where The Field show, the famous show of new contemporary art by Australian artists, not the bush-ranging stuff of Ned Kelly or Arthur Boyd, but this new New York style or international style, forms of abstraction and post-abstraction, conceptual art and so on, Ian Burn, Mel Ramsden, and people like that were producing in Melbourne. The art and language work, that was happening in Melbourne!

And at the same time, yeah, if you went to St. Kilda in ’67, [there was] Pinacotheca Gallery in Fitzroy Street where Peter Booth had his first show, or across the road George Mora and Mirka Mora opened the Tolarno Gallery. First show [there] was by a young artist, 21, Robert Hunter, and they were 13 ‘all-white paintings’, according to the art critic from the Herald, the afternoon paper we still had in those days.

So suddenly we had new artists, new galleries, there were 20, 24, or further down the road, you had Powell Street, or, down the road a bit further, 1970, Brummels opened for the first time in Melbourne, and nearby, the Photographers’ Gallery, in Melbourne and there’s other galleries. And if you thought about it, you’d realise, around the Prahran area, the Carlton area, the St Kilda area, South Yarra area—that was the new cultural precinct of Melbourne. Music, you know, the bands and the pubs and things like that. And photography, photography was there, who could have believed it?—photography galleries in Melbourne! People like Carol Jerrems showing there, Paul Cox, his earlier photographs, you know, followed by all the great films he made later on.

Angela: We’re just at three o’clock and I just wanted to…

Norbert: Oh, yeah, yeah, sorry. You should have warned people about me…

Angela: So I just wanted to get, gauge from everybody if you want to move to questions, or you want to keep going?

Everyone: Keep going!

Norbert: One gets so intensely involved! It was something new, and of course it wasn’t just me, I was preceded by the artists. One of the things at Prahran—let’s look at the photography department for a moment which had a proper beginning in 1971, I was there in ’75 for the first time. The staff, were pretty unusual; Athol Smith, who’d been the major, fashion, commercial, portrait photographer in Melbourne in Collins Street. He was head of department; he actually retired from business to be head of the photography department. But he was faced with the issue, of what the content should be—should I teach a course that would allow a few of the students, maybe to become commercial photographers, be it fashion work, corporate work, for industry, advertising and so on, or, what else…what they call start-ups. Also, teaching was Paul Cox. He’d arrived in a 60s from Holland, and he had a couple of years of technical training in photography in Holland, and he had some knowledge of the European art scene, focussing on the photography scene.

Remember, the photography scene that was in the 1920s and 30s in France, or in Germany in the 1920s, until the Nazis killed it in the war? That was only being revived in the 1960s and 70s, or the American photographic scene, that was still far away, only gradually starting to reach places like Australia, through catalogues, books, and so on. They were very few books on photography, very few picture books that all started in the later ’60s, and it really took one key event that sort of kick-started everything, that people in a sense had been waiting for, and that was the Diane Arbus retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1972. Again, the Museum of Modern Art, again and again, particularly in those times. And the Diane Arbus show, of course, was accompanied by her death a short time before her retrospective. The work in her retrospective collectively had not been seen by anyone, because it was magazine work or work that only a few people had seen in bits and pieces, and here it was suddenly together. And it created a huge impact. The show was stormed, the Museum of Modern Art had the biggest audience ever for an exhibition at that time for photography…no-one could believe it, the show traveled after that.

Also, one of Arbus’s key images was in the front cover of the most important art magazine Artforum, and they had six more of the photographs in the magazine, he first time ever that photography was featured in a mainstream important art magazine. And Diane Arbus quickly was selected for the Venice Biennale, as the American representative, for her works, and, of course, Diane Arbus’s work became a major part of the photographic book of the age that was published in 1977, Susan Sontag’s On Photography, in that famous or infamous chapter on the book of Diane Arbus in On Photography.

By that time, I was already teaching photography at Prahran, but I had three of the chapters of On Photography as they were first published in the New York Review of Books in 1973-1977, and I was very occasionally going to the library at Melbourne University, when I was a student there. I usually just bought my books and studied at home and ignored the university sort of institutions as much as I could. But I was looking for something else and I found the New York Review of Books, a publication that just started in 1963 that became of huge importance for literature, you know, reviews, articles on philosophy, mainstream culture. And it’s in the New York Review of Books that Sontag in the 60s became a celebrated young woman who startled the world with essays like Against Interpretation, Notes on “Camp”, essays on French philosophy, essays on difficult authors here and there, all while she was a young woman, and then she made films, and she published novels. What’s going on? And then she started writing these three important essays for the New York Review of Books. And she got savaged. Why are you wasting your time on photography? Why would you spend months writing essays you know, on the trivial meaning of photography? And of course, yeah, the book proved them wrong, when a major intellectual figure, which she was by that time, would actually write something on photography. The book then was published in ’77. I’ve got a hand-signed copy of it at home and I’ve got a couple of other books by Sean Sontag that I managed to get signed when I was living in America in ’78, ’79 and so on. But again, the change!

Now, something else happens at that time, again, early ‘70s, and that of course, was at the Documenta, for the first time, they invited a photographer to participate, and the photographer is actually two photographers, Hilla and Bernd Becher, the German photographers who were almost unknown, but they produced extraordinary work. I’ll spell it for you, B-E-C-H-E-R, if you don’t know the Bechers. Their works, very standardised, of industrial sites, dead or historical industrial sites, old housing, all photographed in the same way, producing a large edition of very similar buildings—there’s just a small variation from one site to another. Great photographs, very big.

Now, the work astonished people, it seemed to raise photography into a dimension beyond snapshots, beyond documentation, beyond sort of more conventional artistic photography. They were doing something else, and people gradually worked it out, these grey photographs of dead towers, dead houses, rooms. Now, you’ve got to be German, and think of 1970, to see what might be happening in these photos; there’s a metaphor there, there’s a deeper implication about the so called ‘grey zone’ that they deal with. Anyway, what happened at the Documenta in ’71, that was the big Documenta that made it the major art event in the world. The Bechers won the major award for their work, but they won it, not for photography, but for a sculpture, for photographing these mining towers and so on in the old industrial areas in Germany. Of course, they again raised implications about the medium of photography or art that is medium-specific, medium-specific. Notice that more and more art from the 1960s, and afterwards, it’s not medium-specific. It raises other issues. It’s hybrid art. Raising issues about the environment, and things like that. The Becher couple were obviously, in part, in a subtle way, dealing with the awfulness of German history. Have a look at the works because I think they are extraordinary.

Something followed; the major art school in Germany at the time was the Dusseldorf Academy. Eugene von Guerard, remember the German artist came to Australia in the 1850s, and was the first head of the National Gallery School 1870–1881? He went to Dusseldorf in 1830s. He was the major European artist in Australia in the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s. But anyway, the Dusseldorf Academy that had never touched photography before, decided, three years after Prahran, to create a photography department,1974. And who did they appoint? Bernd Becher, as head of the department. Hilla came free, because they did a lot of the work with students at home, nearby.