Australian portrait photographer Jacqueline Mitelman, was born McGregor, in Scotland.

At age 19, and through Robert Richter, Mitelman met Ben Lewin, a law student and enthusiastic photographer. His skilled use of available natural light had a lasting influence on her photography which she started to print in a darkroom at Melbourne University to which she had access through a friend who was teaching in the Engineering faculty. It was a formative experience;

“Working in the dark room was a revelation to me, I was so involved that I lost all sense of time!”

Living next in Paris she became involved in theatre, and only took up photography again once she had returned to Australia, married artist Alan Mitelman, and was inspired to make pictures of her new baby daughter which she processed in the kitchen as it was the easiest room to black out.

Mitelman studied for a Diploma of Art and Design at Prahran College of Advanced Education 1973-76, where her lecturers were Athol Shmith, Paul Cox, and John Cato.

Her marriage to Alan Mitelman was brief. He also had graduated from Prahran earlier in 1968, and later lectured in printmaking at the Victorian College of the Arts before its merger with Prahran visual arts in 1992.

In July 1974 Jacqueline exhibited with fellow Prahran College photography students Matthew Nickson and Euan McGillivray at Brummels Gallery. The next year she showed work in the group exhibitions Woman 1975, which toured, auspiced by the Young Women’s Christian Association of Australia, and at the National Gallery of Victoria in an exhibition curated by Jennie Boddington for International Women’s Year; Wimmin: six wimmin photographers, with Fiona Hall, Marion Hardman, Melanie Le Guay, Melanie Nunn, and also Ingeborg Tyssen, who had started The Photographers’ Gallery near Prahran College.

Carol Jerrems had photographed Mitelman for her own International Women’s Year publication A Book about Australian Women.

After graduation, Mitelman practiced as a freelance photographer specialising in portraiture for magazines and newspapers, album and book covers, and for theatre and music posters. Her portraits of two young girls were published in the 1978/79 issue of the Australian feminist magazine Lip.

In 1984 she joined Prahran lecturers Athol Shmith and Paul Cox, with other significant photographers, for a show Still Movements: A photographic exhibition of images of dance at Heide Gallery.

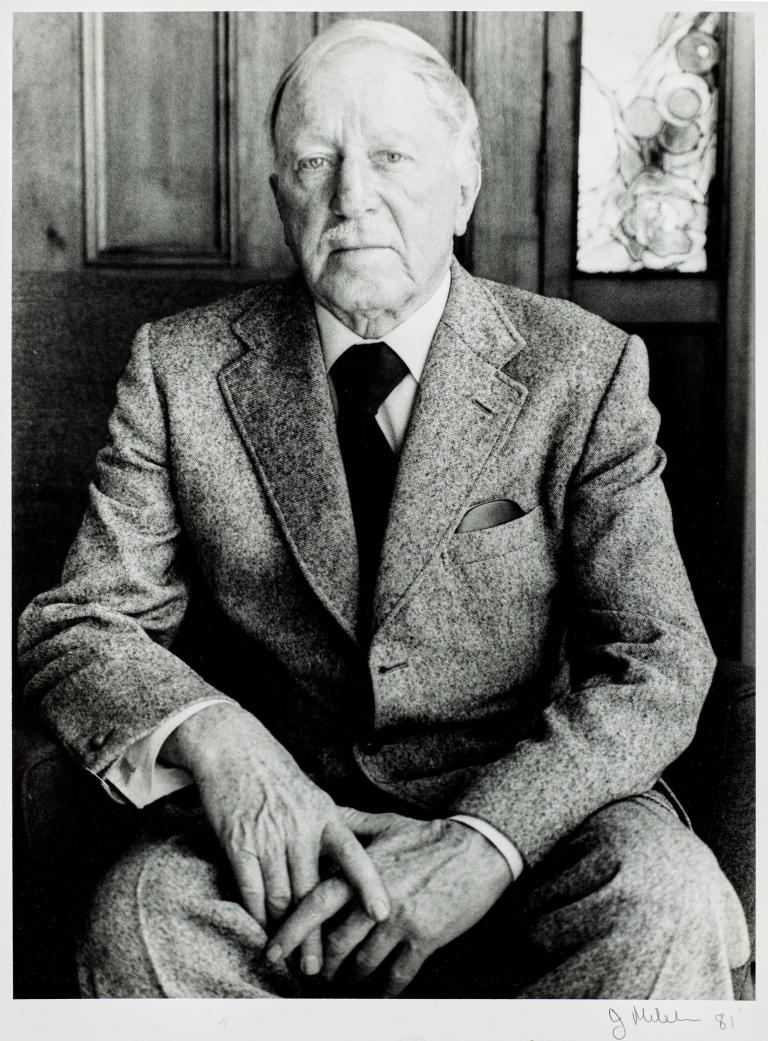

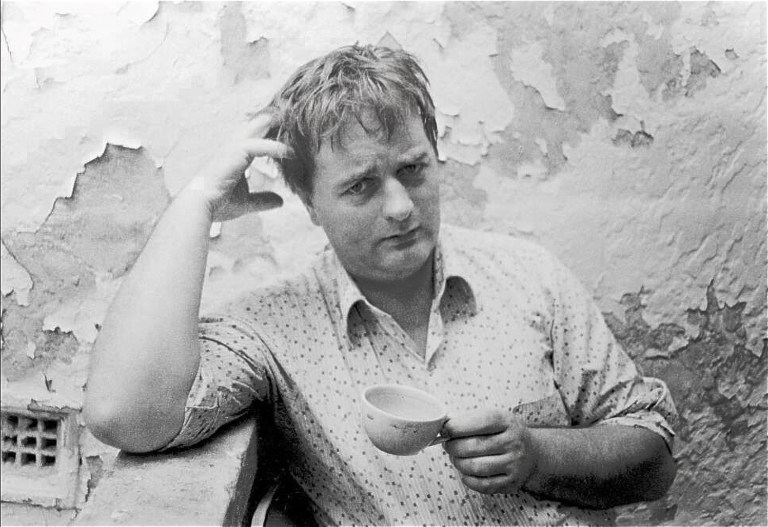

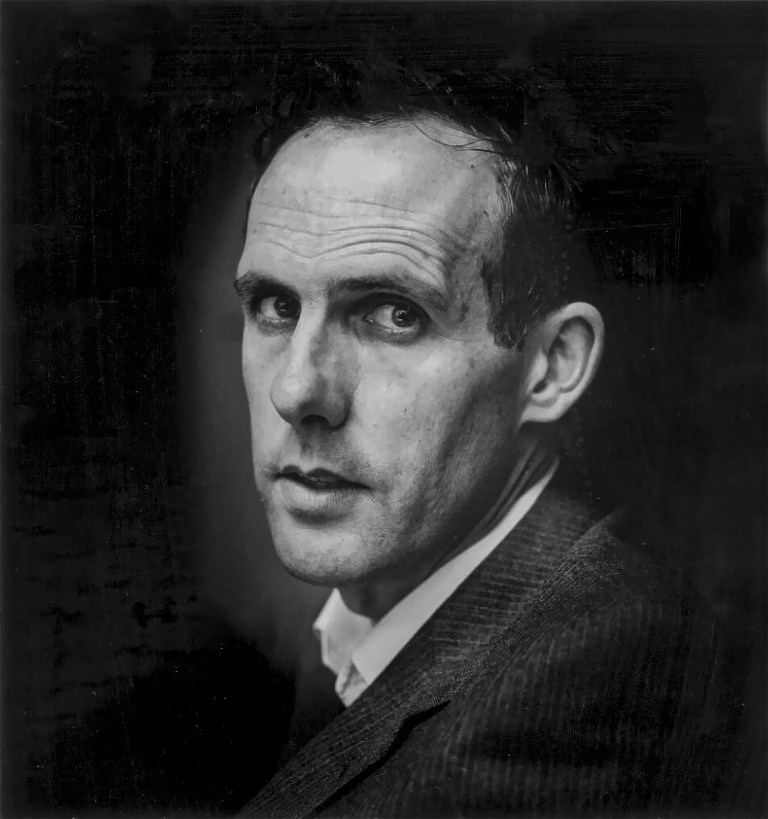

Pursuing a major personal project she sought out Australia’s notable writers, artists and personalities for her subjects. The earliest of the series, from 1981, were writers Hal Porter, Judah Water, Vincent Buckley, and others, in rather stiff and uncomfortable poses which, after a lukewarm reaction to her work in an Age newspaper review by fellow Prahran alumnus Greg Neville, Mitelman softened for more expressive results in later examples, such as this, of Barry Dickens on the peeling balcony of a dilapidated St Kilda flat, who presents just as Mitelman found him, playing himself, as the dispeptic cartoonist and morbid playwright.

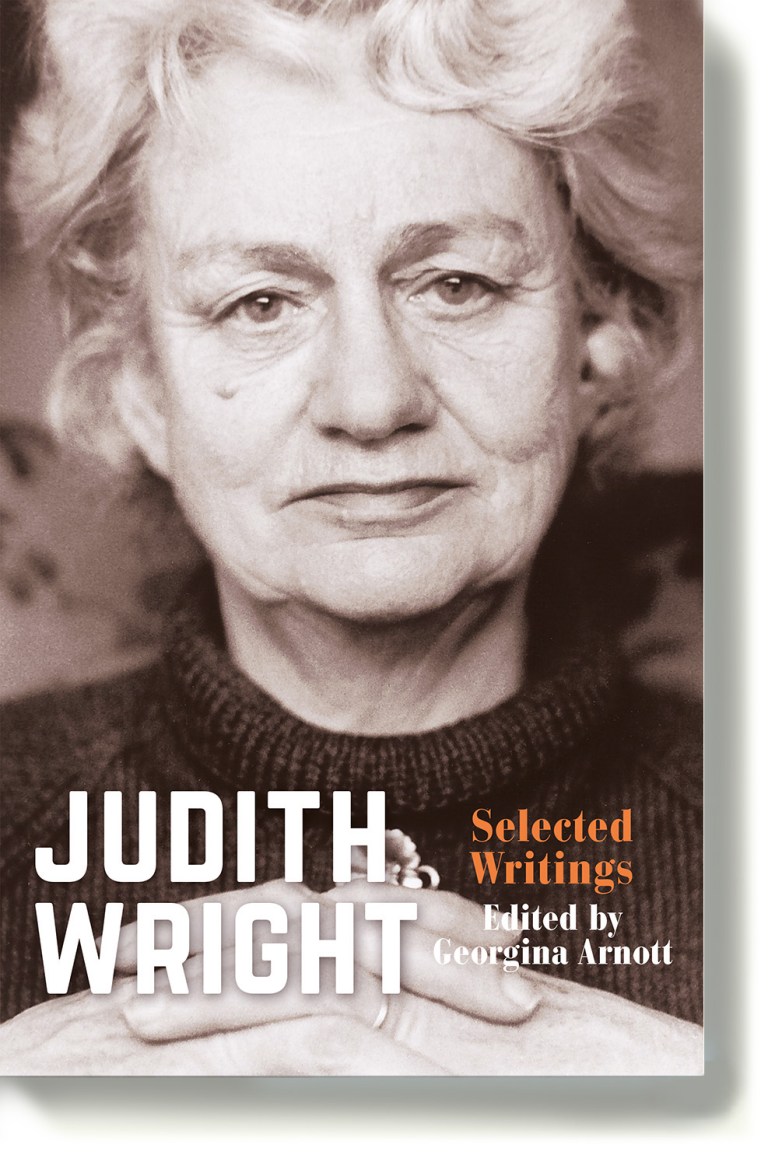

Her exhaustive endeavour built a valuable pantheon of the country’s culture; an extraordinary one hundred and twenty portraits of such individuals presented in her 1988 book Faces of Australia, from works previously exhibited at Luba Bilu’s gallery at 142 Greville St., newly opened a street away from Prahran College.

She managed to portray such luminaries as;

Artist Tom Fantl (also a Prahran graduate; so small was Melbourne’s art world then!) prefaced his review of the book with the statement that in portraiture

“the surface physical features are descriptive but not all telling. It is the personality and psyche which the creative artist must explore, capture and relate. It is the inherent character which the viewer is urged to see, thereby seemingly establishing an understanding, almost a relationship, with the individual portrayed,” before concluding that “Mitelman’s approach is classical and explorative. Classically her sitters look directly into the camera lens, and hence at us, (eg Harry Siedler), thereby drawing us into their space and time. By carefully positioning her subjects, yet making them appear spontaneous we feel watched even as we do the watching.”

Mitelman herself says that;

“The hardest thing is to actually get somebody as they are because people are uncomfortable. If you get through that discomfort and they’re looking very directly at you, the viewer should feel that they looking at them and that they’re making a certain contact with them.”

“…taking photographs is a bit like a temporary infatuation, for me, because, I’m not interested in taking awkward pictures of somebody, so it’s a bit like…that process when you fall in love with somebody.”

The National Portrait Gallery holds twenty of her photographs including those of Dorothy Hewett, Helen Garner, Judith Wright, Jack Hibberd, Peter Carey, Michael Leunig, Christina Stead, Brett Whiteley, Germaine Greer, Ruby Hunter, Murray Bail, Alan Marshall, Kylie Tennant, Susan Ryan, Ita Buttrose, Max Dupain and Lily Brett.

Of Mitelman’s portraits of dogs when displayed in 1998 at Waverley City Gallery (now Museum of Australian Photography), critic Anna Clabburn wrote;

“As with American photographer Bill Wegman’s much earlier portraits of his pet weimaraners, there’s much to be learnt from Mitelman’s comic-yet-serious transposition of dogs into human guise. The anthropomorphic quality of her subjects is both inviting and vaguely disturbing, and certainly makes us think more deeply about our relationship with the beasts we so easily call “pets'”

Her depiction of Miss Alesandra won the Gallery’s 2011 National Photographic Portrait prize, for which she received $25,000 provided by Visa International, marks her successful transition to colour. She had previously won the 2004 Josephine Ulrick National Photography Prize.

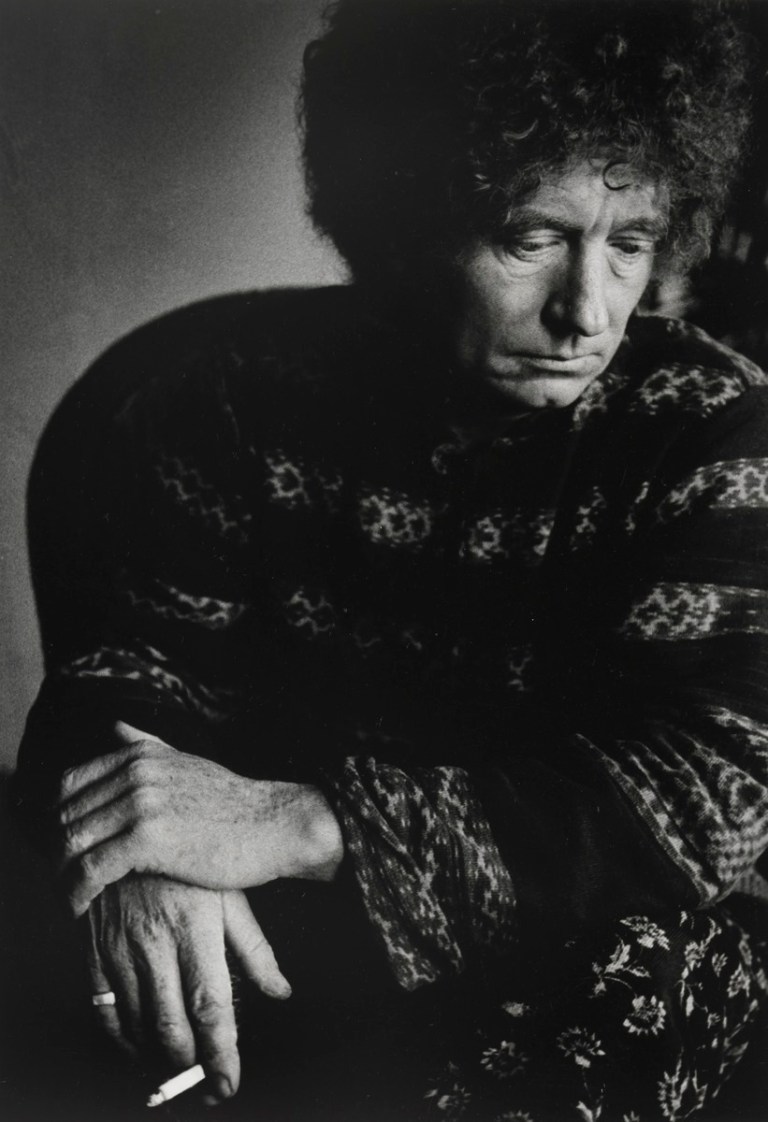

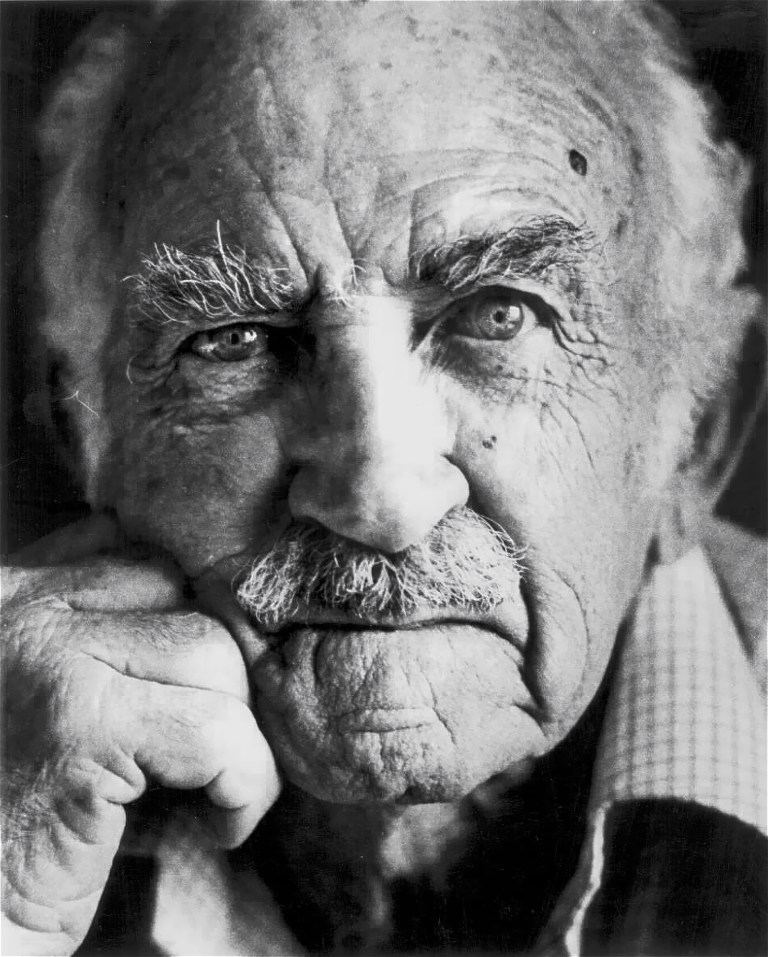

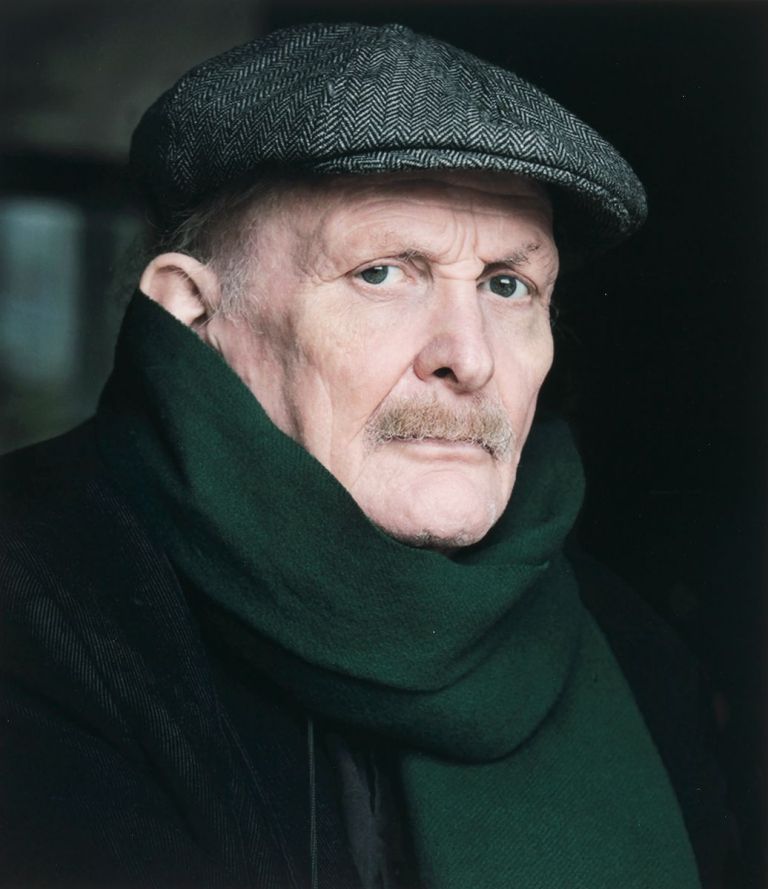

One of the most penetrating of Mitelman’s portraits is that of her lecturer Paul Cox, with whom she remained a firm friend after leaving Prahran. His last film, of the same year, 2015, when Mitelman took this photograph, was fatefully titled Force of Destiny. It drew on his own experience of life-threatening illness, painful treatments, then a liver transplant, following cancer, which calamitously returned in the new organ. The film was also a tribute to his will to continue working and living.

His frailty is evident as he huddles against his pain, and his legendary vitality remains barely glimmering in his steady, determined gaze into Mitelman’s lens, yet he loved it, she reports, because it bears the aura of his great hero Vincent Van Gogh.

NOTE: research for this post has contributed to the entry on Mitelman I have written for Design and Art Australia (DAAO)

5 thoughts on “The Alumni: Jacqueline Mitelman”