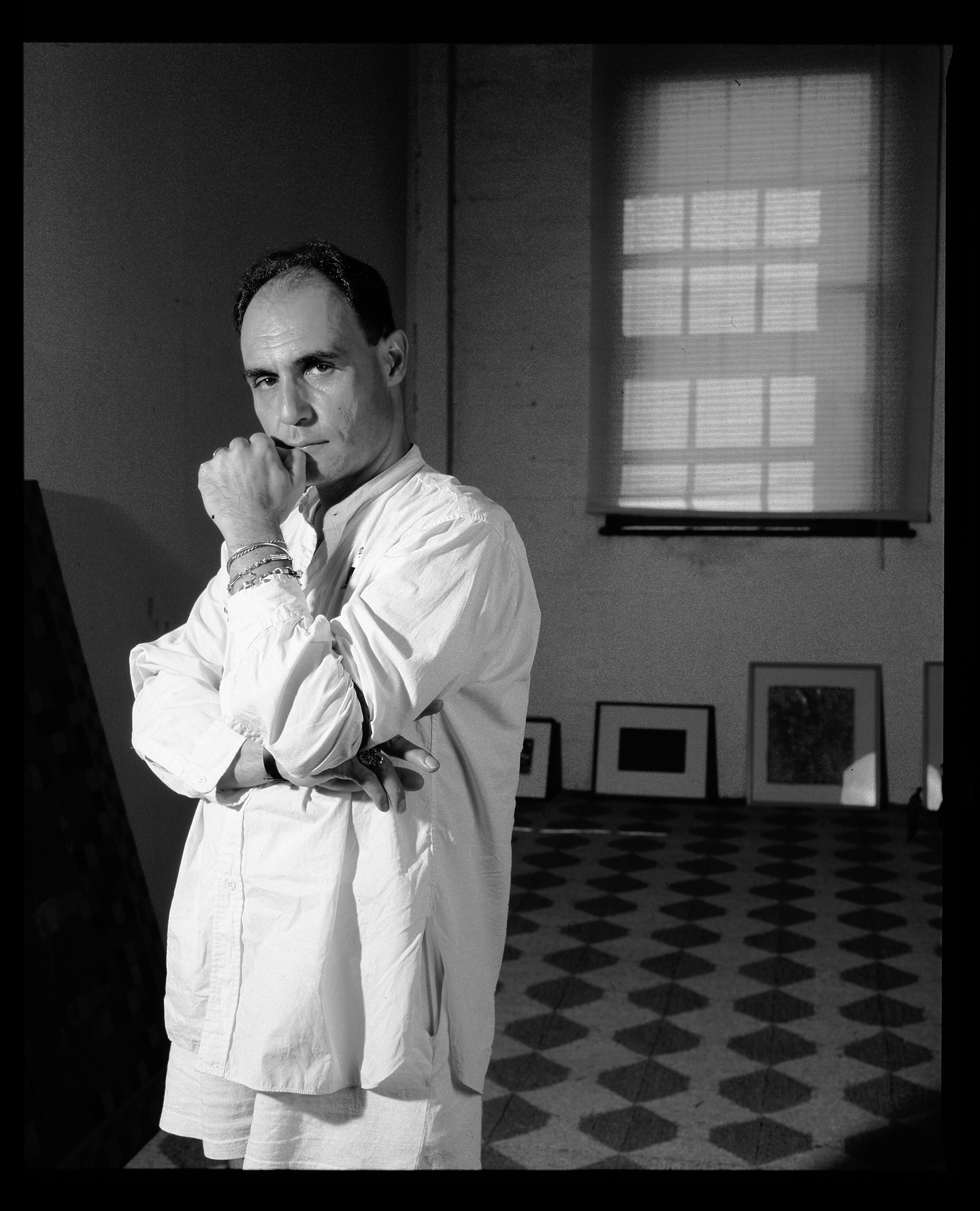

Viki Petherbridge was born in Melbourne in 1954 and grew up in Hampton and developed a love for photography from her father, an engineer with a love of photographing his family and who bought Viki her first camera when she went to RMIT to study Photography in 1972;

“The two years I spent there gave me lifelong friends and my partner, sculptor Augustine Dall’Ava who I met in the first few months and in 2022 we celebrated 50 years together. But the photography course was too commercial and totally uninspiring – and not one of the lecturers, as far as I know was a practising photographer. For example to learn about lighting cans of developer and fixer would be plonked on a table!”

“My friend and fellow student, Leonie Reisberg and I applied to go to Prahran College and we were accepted. One of the best things that happened for us both. The course and lectures were inspiring, with dedicated and practising photographers.”

Senior Curator of International Art at the National Gallery of Victoria, Dr Ted Gott, describes her education;

“As a young art student, Viki Petherbridge received her first technical training in photography at RMIT, an experience—geared to the practical realities of the commercial world—that she found prosaic. It was after she transferred to Prahran College of Advanced Education two years into her studies, that – via the inspiring teaching of Athol Shmith, John Cato and Paul Cox – the true poetry that photography awakened in her soul was brought to flower.”

Having obtained her Diploma of Art & Design from 1976, Viki;

“got my first job in the photographic industry, working at Latrobe Studios in South Melbourne. The following year my first child, a daughter, Jade was born followed by a second daughter, Sophia in 1979.

“During this time I worked various part time jobs until in 1983 when I went to work at Bond Colour Laboratories in Richmond. I was a printer of 16 x 20 and 20 x 24 inch colour photographs.

“In 1984 my partner and I and our two children went to live in Italy for six months where my partner was the recipient of a grant, along with fellow sculptors Geoffrey Bartlett and Tony Pryor. Il Paretaio, in Tuscany, was Arthur Boyd’s villa given to the Visual Arts for practicing artists as a grant for a period of three months. It was my first time overseas and besides Italy we went to France, Germany and Vienna – an amazing experience and I have no idea how many rolls of film I shot but it was extensive and I have used some of them in a juxtaposition with more recent images.”

“On arriving back in 1985 I found a telegram in my letterbox (yes, a telegram) offering me a job back at Bond Colour Laboratories. This job had me at the front reception dealing with photographers and clients. I held this position until 1987 when I was approached by Ian McKenzie from the studio of McKenzie Gray. The photographers at the studio were Ian McKenzie, Robert Gray, Kelvin Aitkin and Brian Gilkes.

“I was responsible for the very busy office and although I was not employed as a photographer, I leant a huge amount from these four talented photographers. During my time there I also had a job photographing the entire collection of the Victorian State Craft Collection at the Meat Market Craft Centre in North Melbourne which resulted in a huge catalogue of every work they owned. McKenzie Gray studios allowed me to print the entire catalogue in the studio. In 1988 I left the studio and our son and last child was born in January 1989.”

Incidentally, it was Ian McKenzie who had been tasked with setting up the photography department of Prahran Technical School (soon to become Prahran College) in the 1960s.

The experience of running a studio gave her the confidence to branch out on her own in 1989 as Petherbridge Photographics, which she still operates, specialising in the reproduction of an array of painting, sculpture and installations by other Australians artists—three of whom, also in their twenties and, like her, just beginning her careers, are seen in her 1976 picture of the three young sculptors, all now prominent in Australian art, above.

The experience of running a studio gave her the confidence to branch out on her own in 1989 as Petherbridge Photographics, which she still operates, specialising in the reproduction of an array of painting, sculpture and installations by other Australians artists—three of whom, also in their twenties and, like her, just beginning her careers, are seen in her 1976 picture of the three young sculptors, all now prominent in Australian art, above.

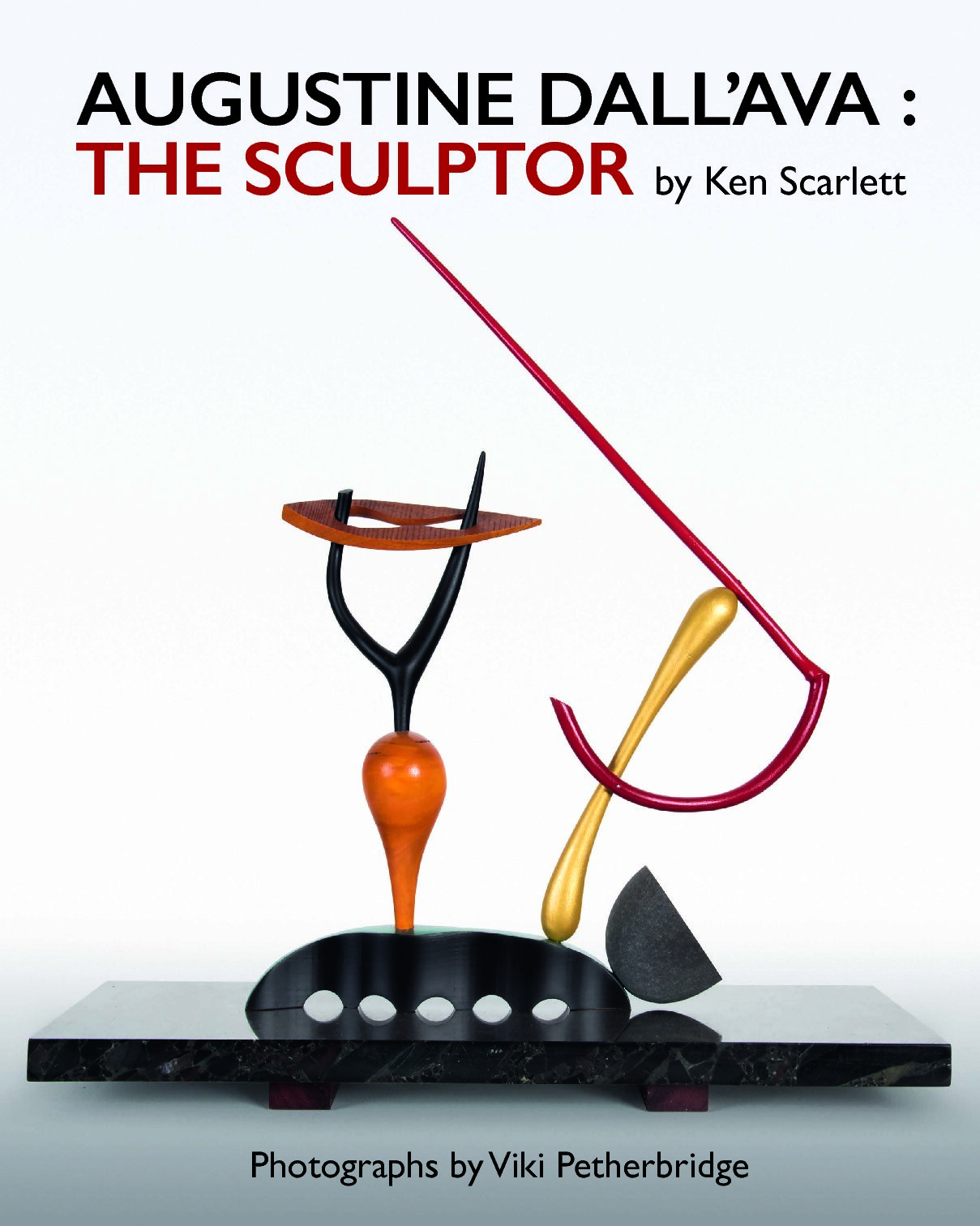

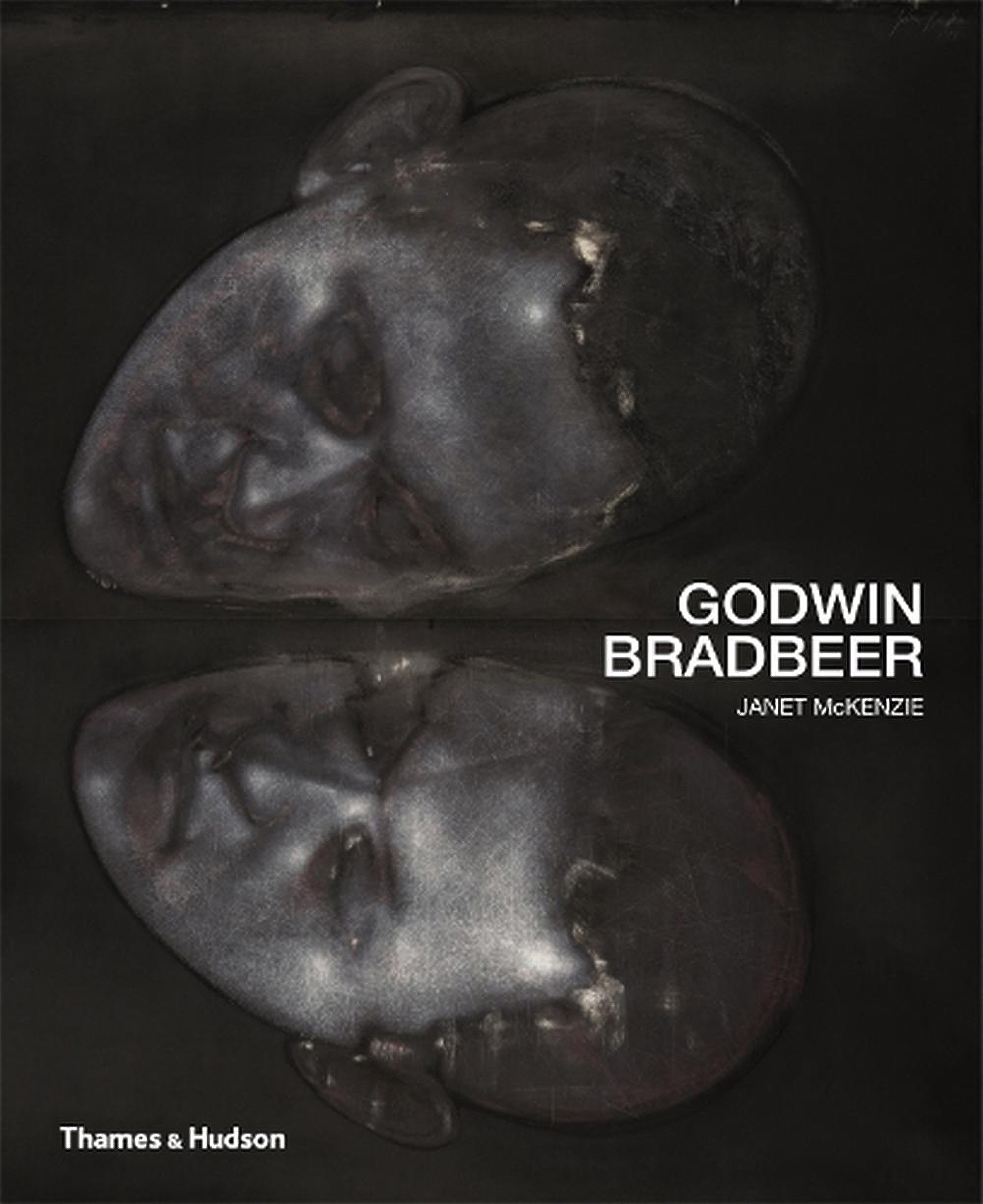

Viki’s pictures illustrated publications including Janet McKenzie’s 2018 monograph on Godwin Bradbeer, and Ken Scarlett’s 2022 Augustine Dall’Ava : the sculptor, on her partner, and illustrations for magazines studio international, Art and Australia and Art Guide Australia. She photographed exhibitions and artworks for the Australian Tapestry Workshop, the City of Boroondara, and galleries including Arthouse, Jan Murphy Gallery, Nicholas Thompson Gallery, Galerie Frank Schlag & Cie., Heide Museum of Modern Art, the Australian War Memorial, the Ian Potter Museum.

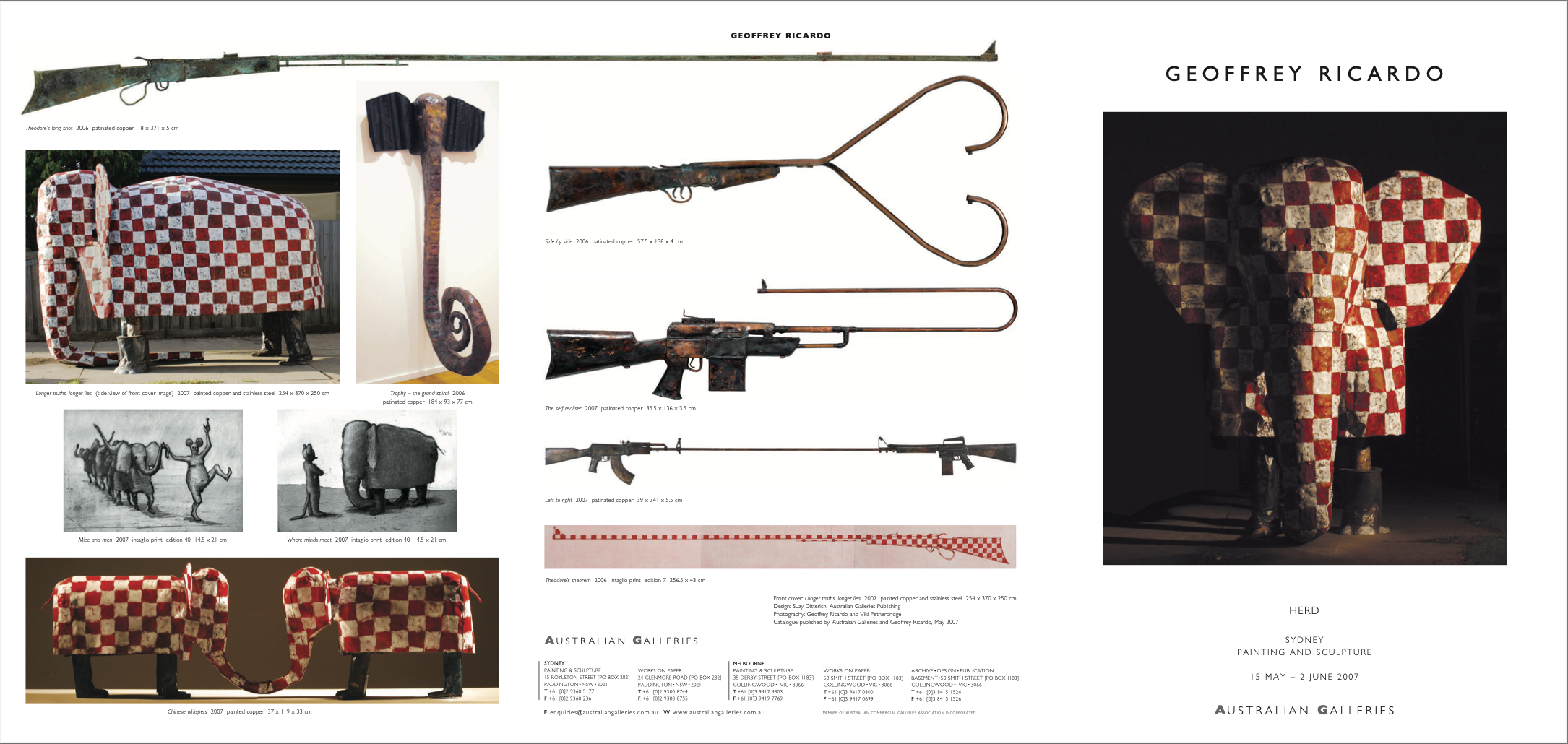

She frequently photographed for the Melbourne and Sydney branches of Australian Galleries’ exhibition catalogues including Selected original prints : works on paper (2006); Rosalind Atkins : arboreus (2005); Julian Twigg: Lone Voyage (2007) and their monographs on artists including David Frazer (2001); Philip Davey (2002); Geoffrey Ricardo (2007), Peter Neilson (2007 and 2012); John Miller (2008).

From 1997 Petherbridge started to hold regular, almost annual, solo shows of her creative works. It is clear that her intimate contact with other artists’ objects in making accurate reproductions of them has made her aware of potentials in her own art, as Zara Stanhope indicates in her introduction to the catalogue for Alter Image; “In Petherbridge’s hands the photograph is a living thing – it can be coloured, embellished, decorated.”

After the birth of her third child, Joseph, in 1989, Petherbridge started making a family portrait every year, choosing different locations, such as a wall with graffiti or a balcony, as a background. One of these won the Courier-Mail People’s Choice $2,000 award in the Energex Arbour Contemporary Art Prize.

With her photograph Window of the Future she linked four generations across nearly a century by combining her grandparents’ 1915 formal wedding day portrait with one made with her Mamiya medium-format camera of herself with husband Augustine, and children Jade, 26, Sophia, 23 and Joseph, 14. Pleased that her image had struck a chord with people with 29 per cent of the votes she saw it displayed as a 2.4m by 3m banner in the Brisbane South Bank Arbour.

Viki explained that she “wanted to create and combine a portrait that is evocative of today’s style of photography—spontaneous as opposed to the more rigid set-up style of the past. The beauty of my grandmother’s dress and bouquet and his gloves give an incongruous mix with us in our jeans and leather and the skyscrapers of Melbourne in the background.”

Her grandfather Ernest had died 4 years after his marriage to Sylvia; “I loved my grandmother dearly and have always thought how difficult it must have been to raise a baby while mourning the death of one you love so much. My purpose with the photograph is to unite history with memory and portray the warmth and love in a family born 100 years apart. It all just fell into place that I could combine what I was doing artistically with this idea of the family…most of the work I do for myself are portraits, as opposed to the commercial side which are static objects.”

Ted Gott speaks of her;

“hand-painting black and white photographs, repositioning them against evocatively muted, colourized backgrounds, and then rephotographing these constructs to create a seamless new image. When in a further optical play, the artist chooses to stitch a string of pearls, an earring or a feathered choker to her finished compositions, her ethereal portraits develop a subtle pulse, seeming to shimmer in and out of three-dimensional perception. In these photographs our tactile awareness is aroused, adding physical sensation to the experience of looking.”

In August 2003 The Age reviewer Robert Nelson attended Petherbridge’s Alter Image at Deakin University’s Icon Gallery he riffed on the word “manipulate” as something “devious and controlling,” but which “in photography…takes an image from naivety to deliberate expression.” Noting that beyond her “clever title Alter Image” she “uses the craftiness of digital technology” sparingly, to;

“spik[e] otherwise natural-looking portraits with an almost lurid intent. Even without the uncanny tricks, the motifs are set up beautifully. But, when a portrait in muted tones has a conspicuously red hand, you realise that a wicked spirit is at work. The red hand insinuates an unconscious guilt and malevolence on the sweet-looking women, who are tied to Renaissance convention. It wreaks mischief upon the patrician archetypes, suggesting that their aesthetics are steeped in cruel and greedy privileges.”

Another Age reviewer Megan Backhouse under a headline “Sensual works of a renaissance woman” noted that amongst the “selection of her Renaissance-inspired portraits, nudes and still lives, dating from 1995 to the present,” some of the “large-scale photographs are hand-coloured, while others have an assortment of small objects attached – such as pearls, feathers or an earring. While they all have a quiet, sensual quality, several verge on the playful as well.” That aesthetic extended to Petherbridge’s preference for vintage clothing which I remember from our student days. Sunday Age columnist Fiona Donnelly wrote in 1995 of her “black fitted crepe and brocade beaded jacket from the late ’20s, teamed with a simple Trent Nathan skirt” that was the ensemble Viki chose for her 40th birthday.

Petherbridge’s black-and-white photographic image of a twisted dead leaf was installed for several months as a giant billboard at the Visible Art Foundation site on the facade of the Hero apartments on the corner of Russell and Little Collins streets, in Melbourne’s city centre. Another remark by Gott is apposite;

“When I see Viki Petherbridge circumnavigating and expanding, through intimate observation, a single object of talismanic natural wonder […] I am transported back to the awestruck perception of the unfathomable divine, revealed to us in the majestic perfection of each infinitesimally small particle of our world, that was expressed so eloquently in 1794 by William Blake: To see a world in a grain of sand / and a heaven in a wildflower / hold infinity in the palm of your hand / and eternity in an hour.”

Also in early 2004 Tania McKenzie curated works by 12 contemporary artists exploring the colour red at Maroondah Art Gallery for Seeing Red in celebration of International Women’s Day. Viki’s contemporary at Prahran College as painting lecturer, the Herald art critic Jeff Makin, singled out as ‘outstanding works’ those of expressionist painter Sharman Feinberg and of Viki Petherbridge, whose “subdued light” he said “offers a hint of violence.”

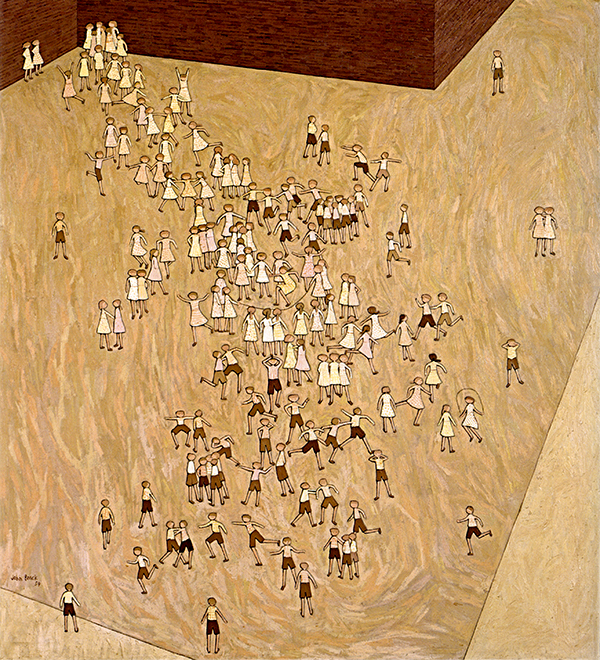

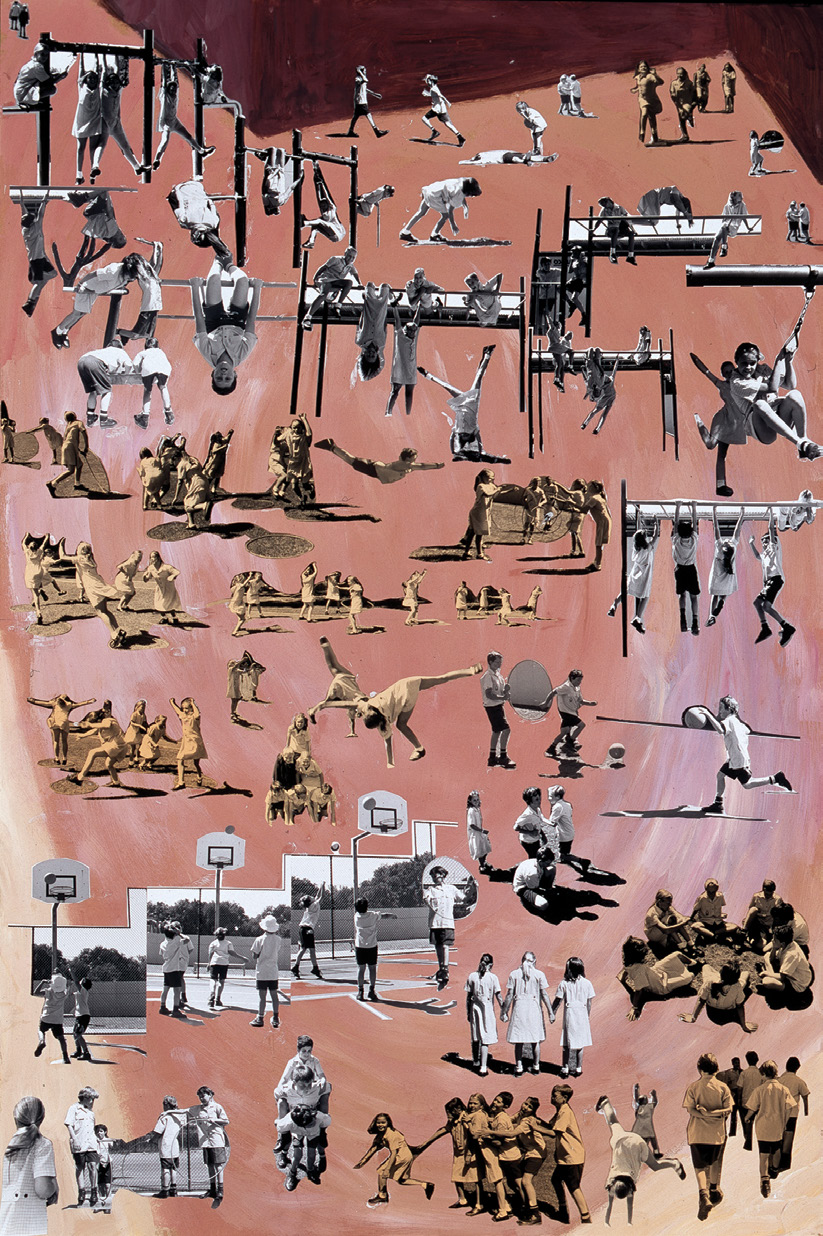

Viki was an inspired and inspiring school artist-in-residence, first at Fitzroy Primary (1988) then in 2004, at Melbourne Grammar School, where artist John Brack (1920-1999) was an art teacher from 1952 to 1962. She asked grade 5 students to study the colour, composition, content and history of his The playground.

She coached them on taking pictures candidly and how to photograph moving figures before each member of the class took photographs of others playing in the school ground, then made collages of the results to assist them in making their own versions of Brack’s original using the same colours and aerial perspective and composition.

The students’ response was positive; Year 5 student Jack Norton enthused;

“I liked working with Miss Petherbridge because I learned how photos are developed and how to dye black and white photos with tea. I also liked using cameras and posing for photos was fun too. The end results rock and I loved the project.”

Helen, Brack’s widow of five years, visited to see the results of the students’ work.

At Carey Grammar School in 2005 she encouraged the students to focus just on line and form without colour, and the resulting ceramic bowls, relief prints, paintings, masks and drawings were exhibited, alongside her own monochrome photographs, at Manningham Gallery in a show called Black and White and Shades of Grey.

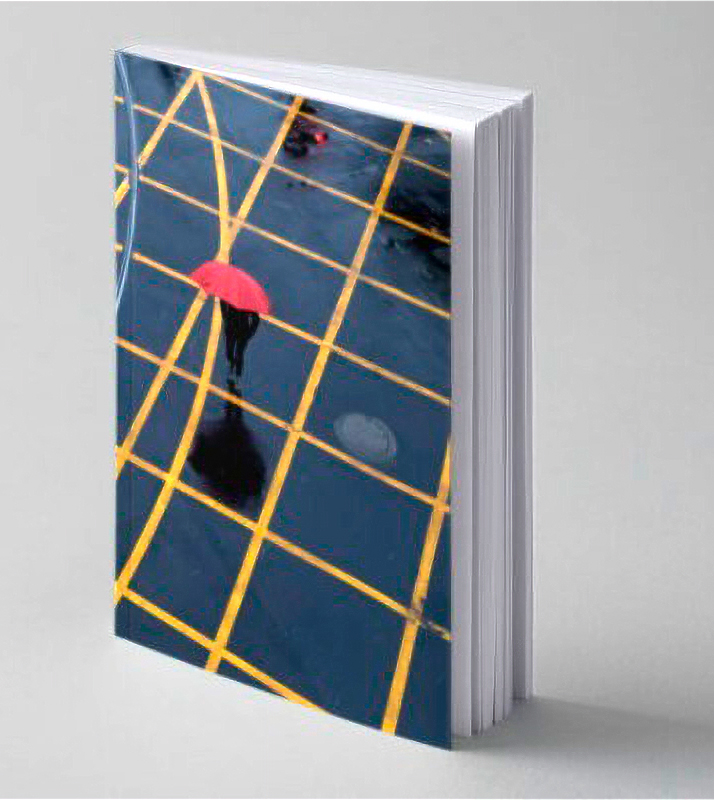

2005 was the same year that Petherbridge, then living in Fitzroy, won the $5000 Best Work on Show prize with her piece, And She Was in the City of Darebin La Trobe University Acquisitive Art Prize at Bundoora Homestead Art Centre for which the theme was art inspired by the past and created by Melbourne’s artists. Her work, part of an ongoing series, combined photographs of windows from her travels around the world with pictures shot in her studio. She said desired an “old-fashioned” look displaying influences of Man Ray and Caravaggio to which she added her own mannerisms; “In this piece I have combined a traditional look with modern touches made possible with Photoshop;” and both she and Nusra Latif Qureshi, who won the Best Work by an Emerging Artist award, created their works through digital manipulation of photographic imagery. The judging panel — Geelong Gallery director Geoffrey Edwards, Australian Print Workshop director Anne Virgo and artist Mark Schaller—selected her work from amongst 45 finalists.

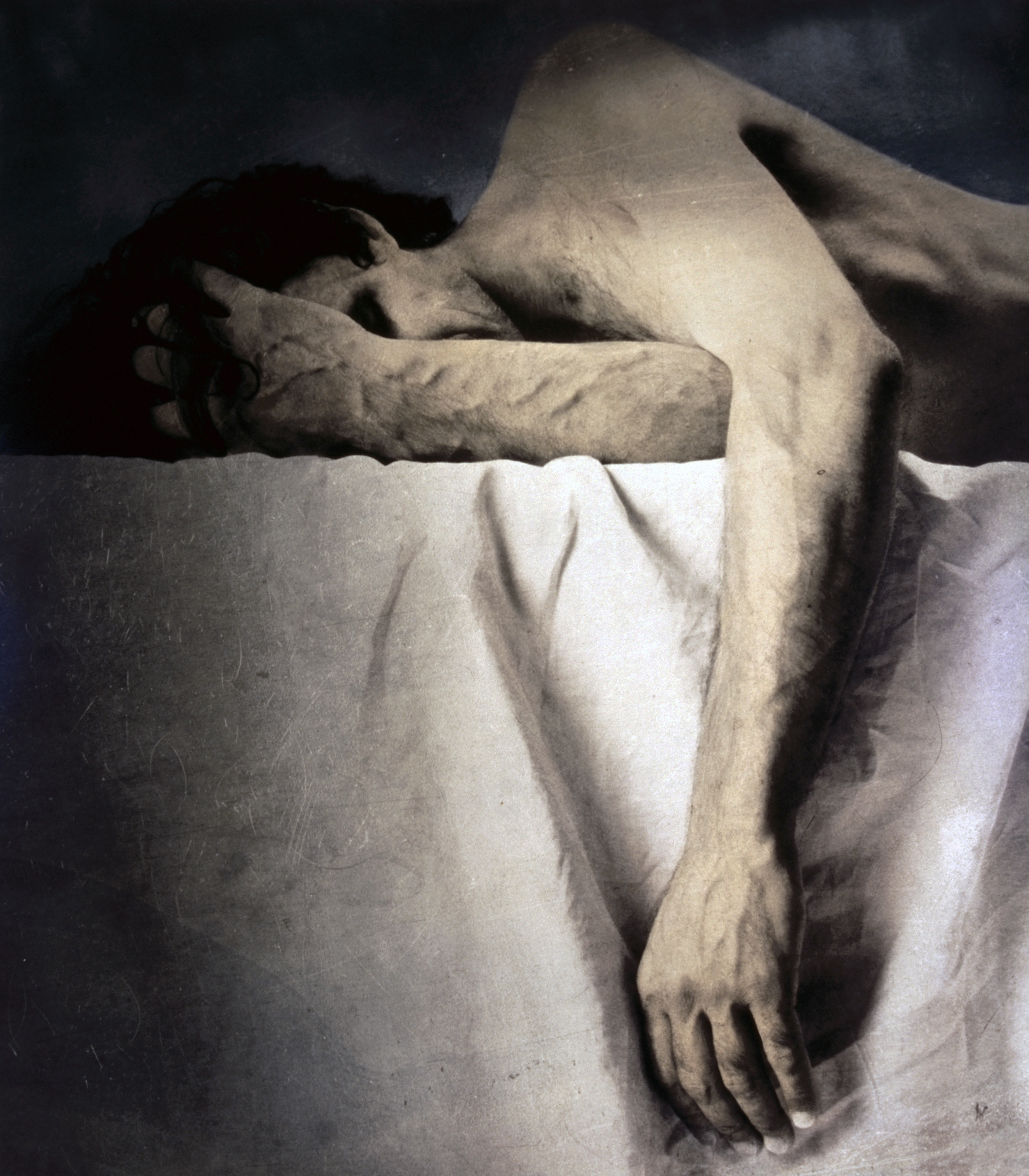

In March/April 2006 Petherbridge joined Pat Brassington, Marryanne Christodoulou, Bill Henson, Leah King-Smith, Norman Lindsay, Deborah Paauwe and Naomie Sunner in Ex[posed photographic images of the body, in an exhibition at the La Trobe University Art Museum and Collection.

Petherbridge participated later in October 2006 in an exhibition Embodied Encounters at the Queensland Centre for Photography with Stephen Hobson, Jenny Carter-White and Susie Adams. Cecelia McNamara remarks in the Brisbane Courier Mail that; “Viki Petherbridge’s The Red Hand is laden with symbolic imagery, with the sanguine motifs aggressively confronting the viewer’s mortality,” a sentiment that Judy Anderson in her catalogue essay for the show supports;

“Human communication begins as an embodied, sensuous interchange, not reducible merely to information. Viki Petherbridge’s series The Red Hand elicits an embodied response, where I feel the image momentarily on my own body.”

Anderson extends on that to comment that Petherbridge underlines controversial political issues like her nation’s incarceration of refugees;

“The recurring image of the red hand [is] emblematic of sacrificial blood…the viewer experiences movement between the perception of sensuous closeness and symbolic distance. In Australia Fair, we experience proximity to the flesh of the young male model, fixating on the red stained hand, and the shadow of the barbed wire across his skin, while on the other we are caught in the powerful semiotics of the barbed wire itself.”

Do we detect in that cruel metal outline an echo of the less forbidding suspended linear forms—metal ‘drawings’—in constructivist sculptures by the 1970s colleagues Geoffrey Bartlett, Augustine Dall’Ava and Anthony Pryor?

For many photographers the still image helped them make sense of the weird suspension of ordinary life during the COVID lockdowns; Mass Isolation Australia archives the project initiated by the Ballarat International Foto Biennale in the midst of lockdown in March 2020.

For many photographers the still image helped them make sense of the weird suspension of ordinary life during the COVID lockdowns; Mass Isolation Australia archives the project initiated by the Ballarat International Foto Biennale in the midst of lockdown in March 2020.

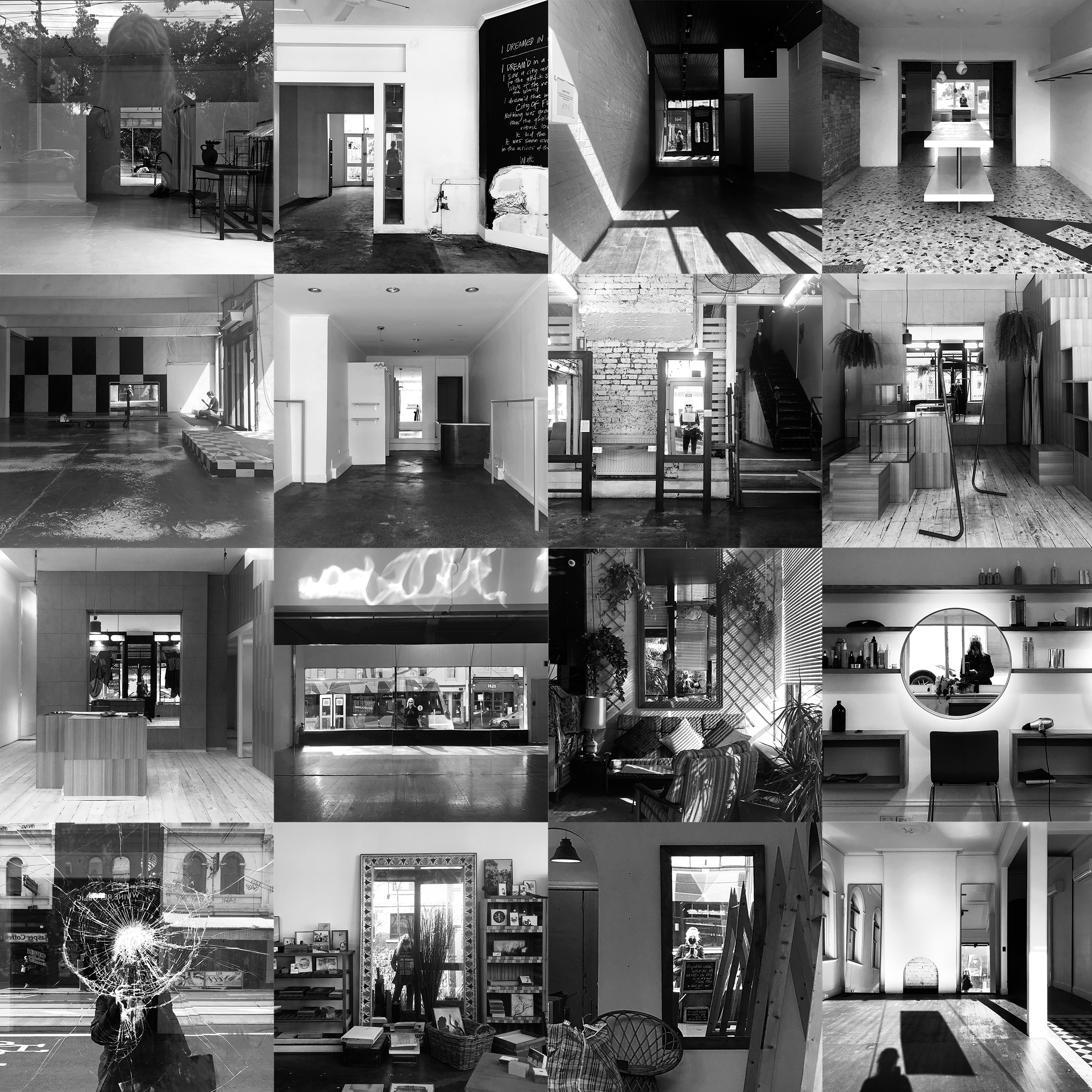

Viki’s contribution Self Portrait with Vandalism During Lockdown vividly encapsulates that lacuna—that now almost inconceivable gap or void—which the pandemic opened up, and its stealthy, ruthless erasure of one’s normal social self. Inner suburban Brunswick Street behind her is deserted apart from a fleeting masked figure far on the other side. The attempted smashing of the plate glass weighs the extent of the vandal’s bitter, violent frustration, but though the lens, the optic that Petherbridge incisively observes it imposing is the rupture; asphalt, concrete, storefronts, tramlines and powerlines buckle as in an earthquake and into the epicentre, her own head, collapse the crazes of its consequence.

As Richard Johnstone remarks of this image; “Petherbridge plays with the long line of storefront photography from Eugène Atget to Vivian Maier,” and indeed it thus marks a return to her photographic roots and the 1970s enthusiasm for the happenstance of the street.

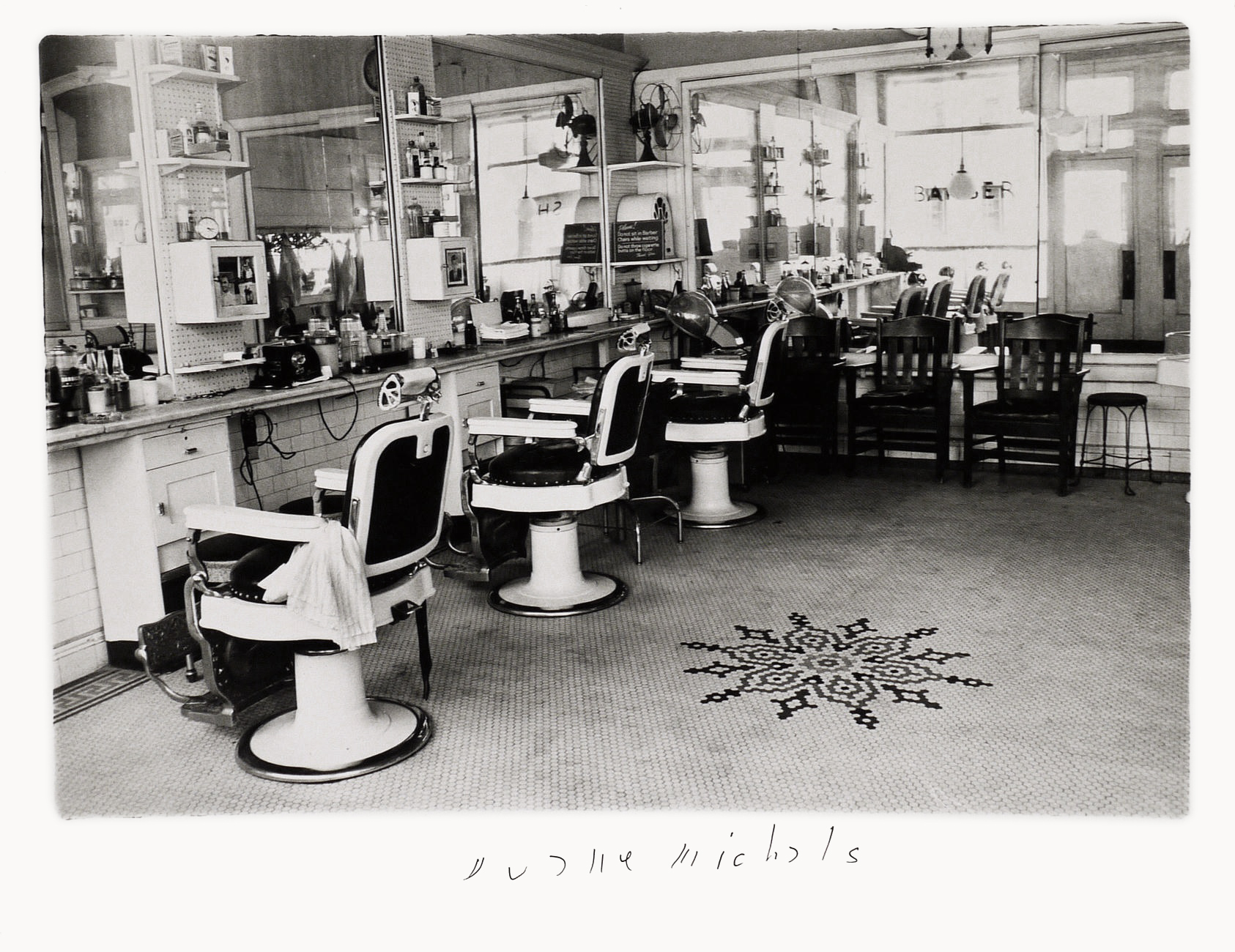

In fact they update, and reflect on a more sinister cause for their emptiness, Duane Michals’ cycle of over 200 photographs forming the series Empty New York (1964-1965). Michals (shown at The Photographers’ Gallery , Prahran in mid-1981) recalls in an interview with photo-eye, that he had made Empty New York in response to Atget;

“I saw this wonderful documentary by a photographer named Becker called Atget (Harold Becker, Eugène Atget, 1964). It was stunning, mesmerizing, and almost like walking through a dream of Paris in 1901 or something… whatever the date. So, I decided to do an exercise on New York in the same way. I began to get up early Sunday mornings and just walk around the streets. If you photographed a bodega with one person in it, you looked at the person…and I was just looking at the environment.”

It is Viki’s insertion of herself, via her reflection, into her deserted interiors that signals her originality.

5 thoughts on “The Alumni: Viki Petherbridge”