ISBN 9781843682509

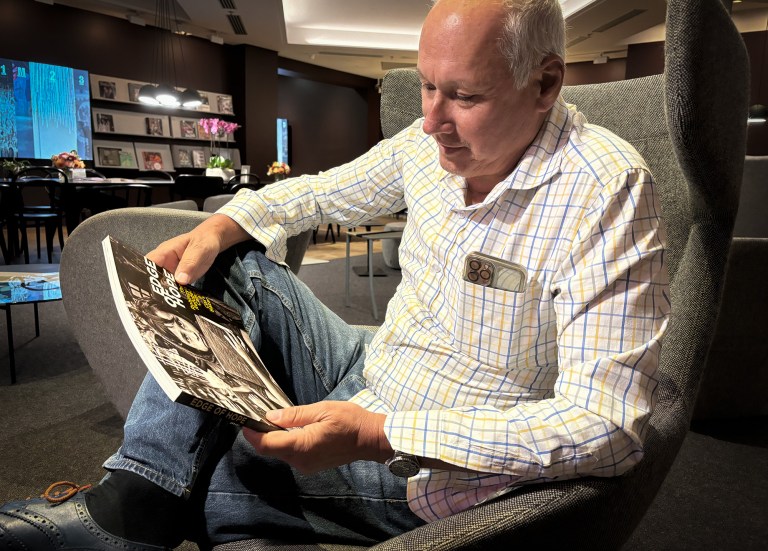

James McArdle: On the train down I’ve been reading what you’ve written for the Nikkei Society website in which you relate your family story;

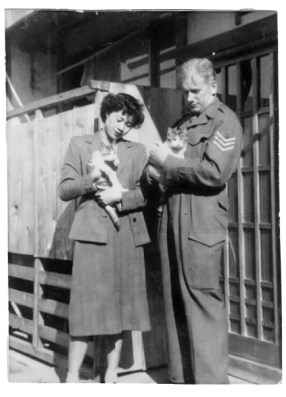

“My sister Coral and I come from a Japanese mother and an Australian father who met in Hiroshima during our father’s service in the occupation forces in 1952. Setsuko Nakamoto and Jack McFarlane met through my uncle Mitsuaki who, as a young boy, came to the camp regularly to practice his English. A romance developed; my mother was attracted by my father’s charm and good looks and my father being in his forties saw that the prospect of marriage and a family life was still not out of the question. Setsuko fell pregnant and Jack had to go back to Australia with the army in order to be discharged. A lengthy wait ensued as at the time the White Australia policy was in force, and even though Jack and Setsuko were married, they were not allowed to make a home in Australia. In the meantime, Coral was born in Hiroshima and it must have been a gruelling time for Setsuko. Would Jack abandon her and Coral like so many other soldiers did their Japanese wives, or would he honour his vows and stay true to their relationship?”

You’ve included quite a lot of photographs, mostly family snaps, wedding pictures, that sort of thing. So who took all those…was it your dad?

Jim McFarlane: Mum’s relatives might have taken them, her brothers maybe…but when she came to Australia she had a tin of photographs, all taken in Japan. A lot were of friends of hers, and workmates at the university for which she worked as a secretary.

You might see them as goodbye photographs, you know?; “You’re going away…you’re going in Australia. Let’s take a photo!”… because in those days that’s what you did with a camera. You wouldn’t take a camera around with you every day as Andrew Chapman does, especially if you were not particularly interested in photography, and only at moments; “Oh, this is important. I’ll go get the camera!” That’s why there’s so few pictures too.

James: That poignant image of your grandmother, whom you never met, when she was saying goodbye to your mother on the station, it says so much about where you come from. I mean, it’s not a photograph, but it’s in what your mother remembered when you took her back to Japan and when you were standing with her at the entrance of a train station. She said;

“This is where I said good-bye to my mother; I can see her here as if it were just yesterday. Somehow she was able to find herself some lipstick (difficult during rationing) and my last memory of her was when we parted: she turned around nodding with reassurance to me as she smiled good-bye. I will always remember how pretty she looked..”

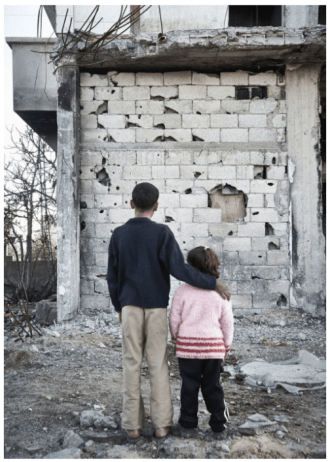

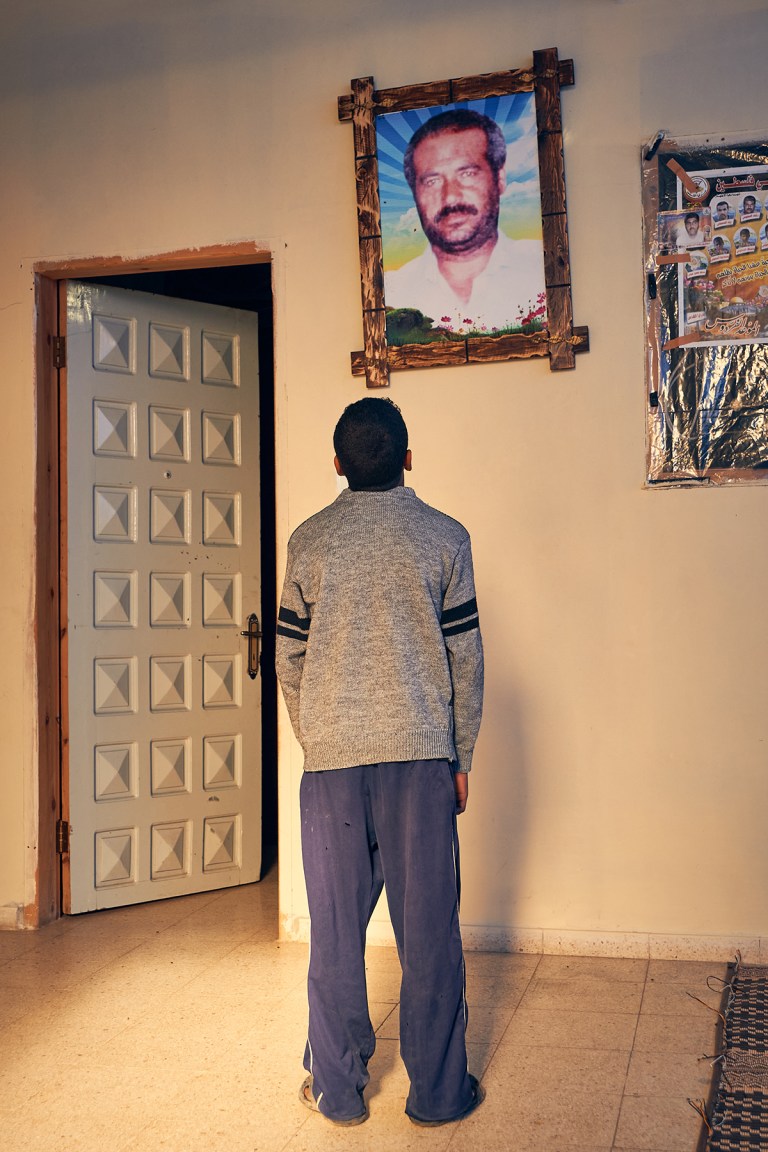

Such a beautiful piece you’ve written there Jim, I feel it strongly relates to what you’re doing now with your preparedness to go into another culture; so how do you feel going to Gaza, Bangladesh or Niger?

Jim: Well I have an affinity with [refugees in those places] because I have a I think I’ve an understanding of what they’ve left behind, because of what my mother left behind… and those memories they have stay with them. But when they go to a new country, they have no one to relate those memories to because their families aren’t with them and its not a shared memory by anybody who’s in that new country where they’re going to. So they don’t get discussed or talked about. It must be that aspect of it must be lonely I think. I recognise them as people who have attachments and memories and a longing for what was in the past.

James: family’s been really important to you, the relatives you know over Japan and you and (sister) Coral have got obviously got a really good grasp of the family history that a lot of people, a lot of Australians, just don’t, who wouldn’t know much about their parents at all because, it’s a kind of cultural blindness here.

Jim: Well yes, I don’t think I know much about my father’s side…

James: That’s the Australian thing, you know.

Jim: His mother died when I was in my early teens and his father, who died before I was born, was on the land but went bust and my father went to Melbourne to be a motor mechanic. He had a brother, Allen and both were sent to boarding school. I only recently discovered that the parents sent them to separate boarding schools. Those two brothers grew up as strangers. Why would you do that or even think “Oh that’s a good idea, we’ll split ‘em up”… just what was done to aborigines.

James: So that accounts a bit for how your father was…?

Jim: Explains it a bit I think…but certainly I know more about my mother’s side of the family than my father’s side, even though records in Japan are scant, most having been destroyed through the war. Fortunately, I have an uncle who’s still alive—my mother’s younger half brother—and he drew up a family tree and explained it to me.

Mum’s grandfather made films. He was a film director and had a company called 帝国映画 ‘Teikoku Cinema’, which means ‘Imperial Cinema.’ Researching into it once I found that one of those films got re-released in Russia in 1993. Maybe it’s in the genes; I became a photographer and my sister’s daughter is an actor.

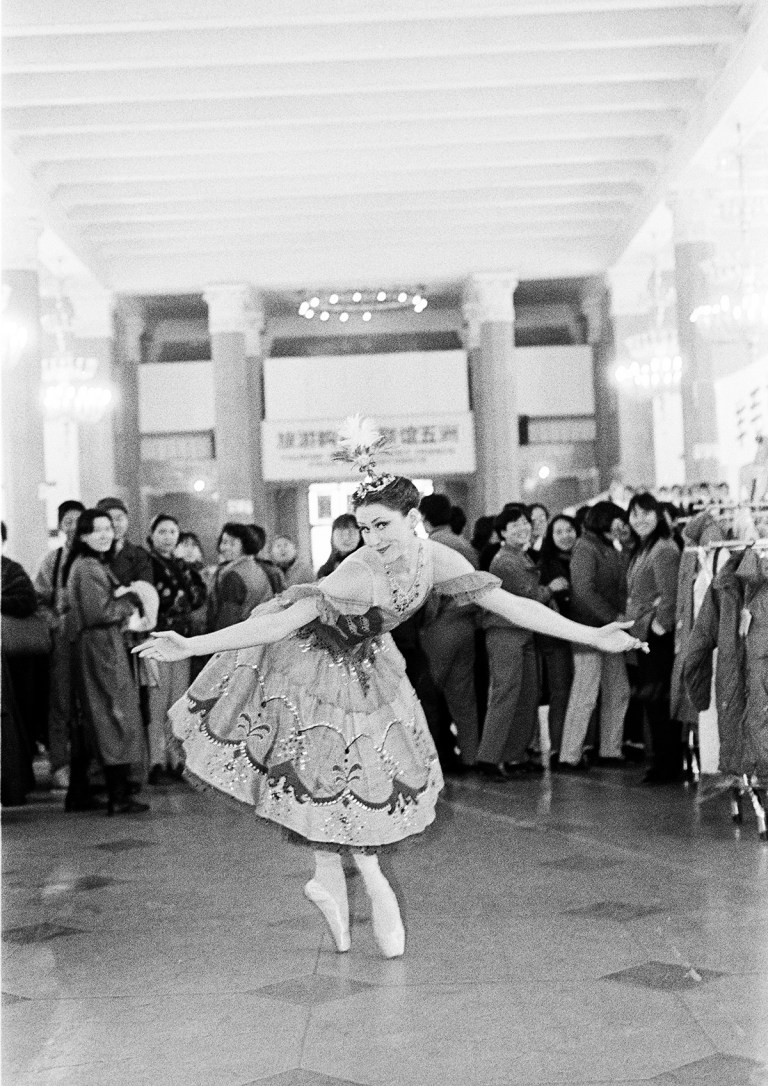

James: And there are other links…those entrepreneurs for the ballet, the Anderson couple, and your partner Yvonne going into into ballet, and you going into photography…

Jim: On the ship, a couple the Ringland-Andersons returning to Australia, befriended my mother. John was a famous eye surgeon and keen amateur photographer and filmmaker.

He and his wife Mary were enthusiastic art lovers and were instrumental in the creation of the Borovansky Ballet, the company that later became The Australian Ballet. The Ringland-Andersons looked after Setsuko, and often invited us as a family to their home ‘Churston,’ at 5 Linlithgow Road, in Toorak. Incidentally, my partner Yvonne was in the administration of The Australian Ballet, and as a photographer they were my client for around 30 years. Yvonne and I see the arts as an industry that is truly multicultural, and that people who love the arts are generally the most humanitarian.

Yvonne knew John’s work through her managing the Australian ballet archive. She was teaching ballet when we met and we were surprised that mum knew so much about ballet. Through this lady, Mrs. Anderson, Mum knew a dancer named Harcourt Algeranoff (in fact an English guy who adopted a Russian name, as many did) who was with Ballet Russes and stayed in Australia. It turned out he was Yvonne’s ballet teacher back in the 1960s! Tragically he died in a car accident, driving, as Yvonne did, to the outlying areas to teach farmers’ kids ballet. Yvonne would go in there first and sweep dead crickets out the hall. Then on a tape recorder she would play the Nutcracker, or Swan Lake for these little kids. It’s huge, in every two-bit town in Australia, there’s a ballet school, it’s like tennis. Her parents moved to Mildura and they had a theatre background. They ran the local store in, in Dareton (population 100) and before television, he being community minded and the shire president, their store was the hub of the town. He’d gather locals who could play or sing, calling themselves the Coomealla Variety Entertainers, and they’d play in community halls. Just imagine if that was still around, if they were still alive and you photographed all of that …it would be the most extraordinary thing, wouldn’t it?

James: So you went up to to Mildura a fair bit when I knew you, photographing wheat silos. Coming from Caulfield, wasn’t it a bit of a culture shock?

Jim: I used to get there on the train, this being before I drove, because we met 50 years ago. I’d catch the train at Spencer Street station on Friday night. No buffet on the train but there was a kiosk at Ballarat platform that closed at midnight and if the train was ten minutes late—well too bad. It’d take 11 hours stopping at every station and sometimes it went through Geelong on the way back…and it takes ten hours to fly from Melbourne to Tokyo!

James: So when did you get interested in photography?

Jim: Well, I used to enjoy looking at photographs. Initially at secondary school I would often go and spend lunchtimes in the library looking at the National Geographic magazine and the British Journal of Photography

James: Creative Camera, had you seen that?

Jim: Look, I knew nothing when I started at Prahran. People talked about photographers and I had no idea who they were, and then with Chris Köller mentioning Henri Cartier-Bresson…”Who’s he?” I thought. I wasn’t very worldly. At tech school I was never taught the tools of research, how to find out more about something you’re interested in was never part of my education. That was a thing that Prahran taught me … what you learn is what you find out, not what you’re taught…you go and find it out mate! Though you might grizzle about it, at least we were taught to become resourceful.

James: Yes, how do you work a Nagra sound recorder? First I’d screw up, then I’d read the manual…

Jim: But what you’re forgetting is, it’s hard to read a manual and understand it. You’ve got to be pretty smart. Try reading a manual now about how to work some sort of software.

James: But you had an engineering sort of background, so do you think you were more technically adept?

Jim: I was more technically minded, still am a bit, because that’s just…photography.

Bill Henson when he won his OAM was asked in interview about art; he said art fits where there’s a gap between the emotional and the physical worlds. It’s so powerful is because it overlaps those two. What a succinct description of what art is……it explains everything. We’ve always sort of skirted around it without really identifying what it is, but he said it, and I thought, that’s pretty fucking good!

Probably John Cato was the most philosophical of the lecturers at Prahran. Paul was away with the fairies, while John was really into that because of the way he photographed the landscape. It was all symbolic, to draw out a picture of a root or a bit of seaweed, it describes his personality as well. He was a very direct person. There’s no bullshit with John; he’d talk about things in simple emotional terms, nothing intellectual about it, but it wasn’t bullshit, it was his belief and he was passionate about it. I believe he’s the only photographer that’s come to terms with the Australian landscape; and it was hard, because, how do you get the dimension, the size of the space, of the air in a bloody picture? How do you convey that kind of feeling of isolation and vulnerability when there’s a big open sky and the sun’s beating down? He did it all…

James: …and he knew that it would take one more than one photograph to do it; as in his 1991 exhibition, Double Concerto: descriptions by Chris and Pat Noone at Luba Bilu Gallery in Prahran, in the guise of two photographers, one shooting in colour and making montages, one in black and white. That’s what he felt was needed to get the four dimensions.

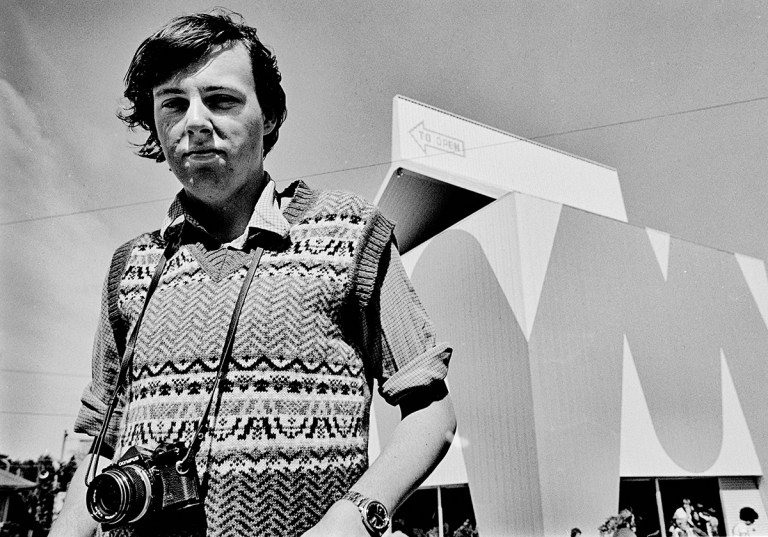

What happened before Prahran and what led you to go there?

Jim: Well, I. worked at General Motors for five years …I was a draftsman there…

James: How did you get into that?

Jim: Because of my love of technical drawing. We did solid geometry at school and had a really good solid geometry teacher there, Leonard Hogg, a little guy and old fashioned; at the end of the class, he’d go round and ask each student a question about the class. If you couldn’t answer you went out the front and you got the strap. What was the class average? 91! And even the stupidest, dumbest kid still got 75.

I loved da Vinci’s flying machines; an aesthetic appreciation rather than anything else, so I did a drafting course at Oakleigh Tech in sixth form, then I got a job at General Motors as a trainee, then in their tech centre drawing car bodies. Later, I made drawings of the parts to be manufactured all curved with surface lines on them …and they looked beautiful.

James: Mind-boggling stuff though?

Jim: We had French curves that were a metre and a half long so you could project; it was all done mathematically with projecting surface lines, and later I became a technical illustrator drawing for instruction manuals, in which there’d be, say, an exploded view of a carburettor with lines radiating showing the fitting of a screw in a washer. I got interested in photography on a technical level. We’d take a picture of the object, make a print, then in the Xerox machine you could enlarge or reduce, then trace over it and that was the first time I actually got into a darkroom. General Motors had a camera club, as did most large companies—book clubs and all kinds—and in the club my boss’s boss was Rick Wallace’s father…

James: Did you have visiting photographers to speak there?

Jim: Oh. Rick Wallace came and I remember an English guy who showed a whole lot of pictures he took in England and they were medium format slides. One picture he did of a rustic farm yard with chickens running through, and he said, you’ve got to orchestrate the pictures, create them, build the picture.

James: So the technical drawing, the solid geometry and your ability to understand perspective and different points of view; does that feed into the way you photograph?

Jim: That aspect of it came later after I started doing a lot of ballet photography, because…

I still do…I look around, I find the background first. I look at the set, then I put the subject into it. That’s why there’s a consistency about my backgrounds, because I look at the situation first and I build from there.

There’s a personal side as well. Simply because of my background and what happened at school and so on, I always felt separate, an outsider. A camera became my tool through which I could observe the world to perhaps make more sense of it and it still is. I don’t understand anything until I photograph it, because in order to photograph it you go through the thought process of, you know, what is it? what am I trying to say here?

James: And is it a sort of passport as well in terms of getting into places from which you would otherwise be excluded?

Jim: Yes. The most fascinating thing, that no one taught us, is what you learn through photographing. No one told us that. As a commercial photographer, you’re always inside the ropes…you go straight past all the people waiting in the queue and you’re talking to the people that actually made this, or are part of it. And you have to understand what they want, what they’re doing, so that you can describe it in photographs. Anyone who’s mildly curious about anything, photography is the way in. Such a variety of industries in which I’ve worked and there’s only two in which I haven’t; the military, and the corrections system, in jails. Think of that, I mean, who’s ever done that, who ever steps inside the ropes of such things? If you’re curious, it’s just extraordinary, extraordinary. I feel so, so lucky, so privileged. I’m an outsider, but I’ve been on the inside of a lot of things; it’s a rare contradiction.

James: Did you feel that at Prahran with the other students; a bit of an outsider?

Jim: I thought that they were much more informed than I was. Chris Köller was pretty switched on. It just changed my life completely. I mean, the doors just flew open.

James: And you stuck it out. A lot of people didn’t. You know, a lot of students didn’t make it all the way through.

Jim: Perhaps I was a little bit old fashioned and lacking in confidence so I thought it was really important to finish something and have a certificate

James: Of the people that you went through in your particular year how many people do you have anything to do with?

Jim: Well, Chris Atkins and I were friends for a long, long time, but then there was a sort of falling out, so that was it; Mike Sankey, and though he moved to Queensland we still keep in touch; Chris Koller I’ve been seeing recently; Gavin Oaks who was only in first year with us; Andrew Chapman, though he was only in my third year; and of course, Colin Abbott I see from time to time, but he was not my year.

But the most extraordinary thing is the Prahran culture. When I taught at Deakin I met up with Kim Corbel whom I’d never met, but within five minutes, we were talking the same language, no explanation required after 40 years, you know, it was embedded into him. It’s hard to put your finger on it. If there’s any one big thing that I got out of being at Prahran, it taught me to be critical and that opinions aren’t good enough; you’ve got to know what you’re talking about. People viewed each other’s work critically because it was competitive on one level, but in the end we were all just interested taking the best photographs. The approval of your contemporaries….that’s what it’s all about, all that’s ever mattered to me, to earn your place in their eyes.

In a series with Paul McCartney some music buff analyses the Beatles music with his sound deck removing all the voices so you hear just Paul’s bass. Talking to McCartney about his bass technique he read a quote full of praise for Paul’s originality and his technique. It’s just glowing. He said “Do you know who wrote that? John Lennon”. Paul said, “He never told me that, but I’m glad he told somebody.”

James:…and if he’d been at Prahran, he would have been told?

Jim: Yes, you know, wise people are aware of what they don’t know, and I think a part of teaching is to get people to that realisation. When you open your mind; “I haven’t heard this before, I’d better listen to this…” And this is part of that emotional world that you know, that Bill Henson was talking about…there’s no right or wrong there, it’s about a whole lot of other things; about intuition and your experience, the way you see, how you fit in.

James: When you were at Decent Exposure studios, did that feeling of collegiality continue?

Jim: When I started at Decent Exposure, I wasn’t an advertising photographer. I was doing annual report stuff, and still a little bit of PR and work with the Ballet. These other guys were high-end advertising people and everybody looked up to that because they worked for advertising agencies and they’d get big accounts. But none of them looked down on me. Introducing myself and my work they said, stop, stop..I don’t care what you do, it doesn’t matter, you’re here. Everybody showed each other things; no secrets. In the end you learned the most from the assistants, because you’d be shooting something, scratching your head wondering how to do something and the assistant would say, oh I worked on this a couple of weeks ago with X and we did it this way. Not only was it with photographic technique, but in learning the computer when digital came in. I never did a digital course, I did it flying by the seat of my pants, but that’s where you learned from the assistants; “Really? You’ve got to do that do you?” …just invaluable. And that’s what Prahran taught us, to get information from anywhere, because you had to.

James: With your food photography, I’m interested in how that kind of collegiality worked in

that relationship of photographer with food stylist.

Jim: Though some photographers did, I never regarded the food stylist as being my servant. I could recognise right from the word go that without them I’m nobody; because I can use all the lighting technique in the world but if the food looks bad, it’s going to be a bad photo. Ha…if you’ve got a good food stylist and the food is presented nicely, all you’ve got to do is get the bloody thing in focus and you got a nice photo…your mouth will water!

Up until the time I was doing food, photography was kind of lonely because it’s just you and the subject but when you have someone to work with, you talk about ideas and you do them together and you support each other,. Two people are bigger than one, and two people are bigger than two…

Caroline Westmore was really good to me and one of the reasons why I tried so hard is because I didn’t want to disappoint her. I mean to please myself is not enough, there’s got to be something bigger. I’m a bit of a lazy bastard, but with someone else, it’s bigger than just you. It pushes things along because you have respect for that person and you want to please them, not disappoint them. That’s a really nice dynamic because I’ve never been a leader.

James: So when was it that you got into food photography?

Jim: Oh at Decent. I was always interested in food and no other photographers I ever worked with, had worked in food, so I never knew any food stylists and I never really saw food being shot, apart from a couple of short weeks on work experience for Prahran when I did work experience with Peter Walton.

It happened because of Andrew Chapman who was doing the annual report for the Dairy Corporation and one shot, a still life of some cheese and biscuits, required a studio and Andrew wasn’t a studio photographer, so he said “No mate, Jim McFarlane, he’ll do that part for you.” That’s when Carolyn came over, as she was then working with the Dairy Corp. Doing the shot together, I said to her, “Look, I’ve always wanted to get into food photography…can we do a portfolio together?” She said, “No, I’m working full time but I’ll take your card.” Six months she called; she’d left the Dairy Corporation to go freelance and suggested we put a portfolio together. She treated it as a job. We’d look through magazines and she said, “Well, we’ll need a shot of meat, we’ll need some fish, some beverages, and an ice cream shot.” We got down and we shot it all in about six days…bang, bang, bang, then went out showing our folio together, marketing ourselves as a team, as different from most food photographers who’d call in any food stylist.

The partnership was really good because, she was able to talk to clients about a whole lot of things in which I had no expertise. I didn’t know that large food companies would have a recipe made for a particular product, perhaps an old product dressed up in a new way, or it’d be a completely new product. They would make a prototype of whatever it was, a chicken nugget perhaps, as when they’re being photographed they’re not yet in production so it has to be specially made. Caroline was able to ask them well what machine they would make it on, and she might say “Well, it’s not going look like that if you use that machine.” She had this level of technical know-how—it’s not just food styling—she’d done food science and was more highly educated than me, yet in the industry they’re paid half of what a photographer would get because they’re women. And yet, I just stand around and push the button. Caroline says to me “you can take the picture now” and I take the picture.

That was great fun but I was starting to miss photographing people because I love photographing people. Doing food, you’re not photographing people and you’re not traveling much either, but stuck in a studio, never experiencing the seasons…nothing’s perfect. Nothing’s ever perfect. But I had a lot of enjoyment.

James: You’re a man who enjoys food.

Jim: I never got hungry!

James: When did you get into documentary work?

Jim: The beginnings were at Prahran of course, when we were shown the photographs of Louis Hine and the Farm Security Administration…a passion of mine always…the sort of photographs I admired when I was at school, at lunchtime. But I knew right from the beginning, that you can’t make a living out of it, certainly not in Australia. You had to be somewhere else. I loved photography so much I really didn’t care what I did, as long as I was doing photography, so I went down the commercial road. I learned an awful lot that gave me the technical ability to do it properly. That’s the thing; you learn things from anywhere, as I did in doing wedding photography, the technical aspect, but also dealing with people and developing an eye for detail.

When you don’t speak the language of people you photograph it’s important to get them to take it seriously. The technique I use for those situations is what I learned from Athol; hand gestures. Walking in, you just use your hands, you just look at people and all of a sudden they become quiet and you’ve got their attention. You don’t have to say anything. If you want someone looking in a certain direction you put your hand up, and they’ll look at your hand. They respond immediately.

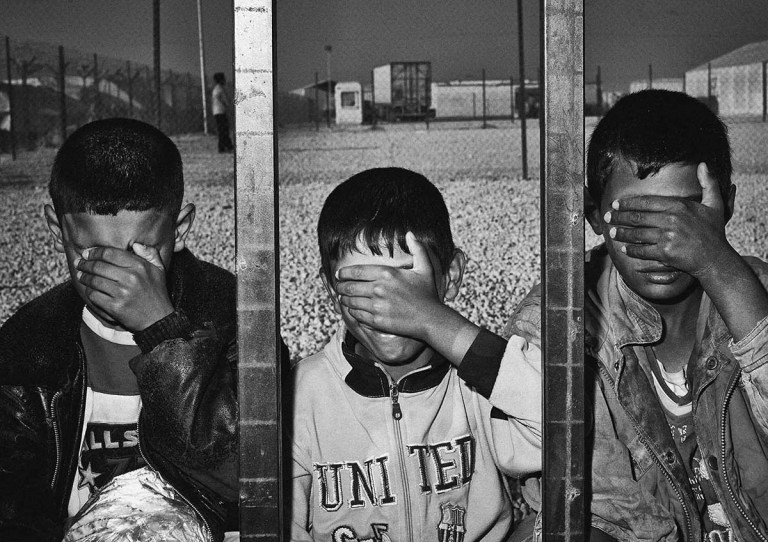

For these photos, of the Rohingya refugee camp in Cox’s Bazaar in Bangladesh, we had two minutes because we were going from one dwelling to another in these camps, and it’s all hurry hurry hurry. You have to be ready for it, it’s all that wedding technique, and using a bit of flash.

James: But you’re not conscious of flash looking at these. You manage to to pull some detail out of shadows but it doesn’t look like a news photo; it’s really subtle technique…

Jim: Working with groups of people speed is essential, but the other thing is being a bit of a sticky beak. I used to love, doing weddings; going to the bride’s home first, from room to room, looking around, you’d notice the pictures on the wall, the ornamentation they had, the doily on top of the TV set. I mean, who gets to see that? They’re in not even in the room, and there are their lives in front of you. I missed that after I stopped doing weddings. Then you go into someone’s hut in a refugee camp and you look around, you see the things that aren’t there. There’s nothing on the walls or any decor, nothing that gives comfort to the eye. It’s all completely practical, just as in that famous Walker Evans photo of inside a sharecropper’s shack, the few knives and forks shoved behind a tacked-on piece of shingle. You look around and do a calculation; you see the cooking utensils, you see the pots and pans, a pair of shoes and clothing. There’s a family of six there, and you think, all of that will fit in one suitcase.

These are the things that come to you intuitively because of what I’ve done before; it’s something you don’t have to think about…just [clicks fingers] blatantly obvious.

James: It’s a tremendous achievement to have got to this, Jim. You’re producing photographs that matter and it’s not just political level, but on a social level of people’s understanding of other people.

Jim: I think it’s only because I’ve had the opportunity to, I’m very fortunate to stumbled into it…that I met Anthony Dawton when he came to Decent Exposure and we struck up a friendship and shared a passion for social documentary. And you know, it’s really been all his work; I’ve just tagged along for the ride.

Photographers don’t generally work in pairs and rarely at such a distance; he’s in London and I’m here. None of this could happen without internet, without free phone calls overseas; “OK I’m going to see you in Lebanon in two weeks time.What are you going to bring? Oh, not much, as little as possible.”

And no preconceptions.

I learned very quickly that if a client briefed you to go and take a photo the actuality was always different to what I expected. So I’ve learned now not to think about anything, just be prepared. Go there with a preconceived idea, with a certain attitude, and you’ve got to immediately unravel it all when you get there…you’re immediately wrong-footed and it wastes a lot of time because it takes that mental adjustment, and in doing that mental adjustment, you’re not taking anything in. You have to get rid of that before you become receptive.

So when people describe what we’re going to shoot, I say “OK, I got it …” and give it no more thought. I think about how to take the minimum amount of gear possible because I don’t want to carry it around.

James: So what’s Anthony’s background?

Jim: Photography-wise, he’s self-taught.

James: I suggest he’s learnt from you, Jim…

Jim: Ha…I told him a bit about flash. He’s never done a photography course, but drifted into photography and became known for his editorial work. But the person that gives us work is among Iraq’s most acclaimed artists; Dia al-Azzawi, for whom Anthony photographs his work and who for some of our projects incorporates our photographs in his prints.

Anthony’s also well-known in the Lebanese community for weddings; he’s the preferred photographer for Claridge’s, you know, the London hotel, where if someone decides on the spur of the moment to get married, they call him to cover it.

In the case of this book, he was called to photograph the wedding of a wealthy Bangladeshi family. The son married a Scandinavian woman and invited friends in London to a big reception at Claridges. The mother, a photographer herself who goes on photo safaris, got talking to Anthony asking, beyond wedding photography, what he was doing. Coincidentally, Anthony, had just finished his project during Covid photographing homeless people in London for a book Not London to be launched in the following week. She came and was really impressed, and told him about an organisation in Bangladesh; “you have to get over there and help them…” She organised our meeting with the Amal foundation. So things can happen from anywhere…

Through Anthony I’ve met some pretty influential people, and of course he has people over there that back him, donate money. Dia Azawi has attracted a lot of money for our project; he’s the one that got us into Gaza. There’s another lady, originally Syrian, but who lived in Saudi Arabia for a long time, and from a very wealthy family and she’s got her own charity organisation in London. She got us to Niger for UNICEF in 2008 and she’s funding us for the Gaza book.

James: Well, photography is all about being in the right place at the right time.

Jim: As Anthony says in the foreword to our book, wherever we go, trouble ends up happening there!

10 thoughts on “The Alumni: Jim McFarlane”