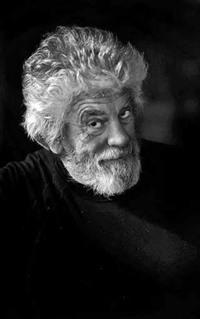

Attending from 1965-68, Ian Macrae was among the earliest to study photography at Prahran College and has spent the major part of his career directing film.

When asked whether it was an ambition right from the start, he remembers his father “was interested in photography and had a 35mm camera when most people those days had box brownies, but he mainly took shots of flowers.” Ian took up photography when he was about 11 and became interested in visual trickery, an early example of which was of another friend boxing against himself.

Having nothing else but a Kodak box camera, Macrae put black cloth against a wall and framed his friend on the left, then over on the right, so both shots were double-exposed on the one negative. With no enlarger, he did have means to make contact prints from the Box Brownie negative so it was large enough to view practically.

Born in Adelaide while his mother was visiting her parents there, Macrae grew up in Melbourne in the bayside suburb of Beaumaris, where creative things were going on, as they had done since Arthur Streeton, Tom Roberts and Fred McCubbin rented a house there in summer 1886-87, Clarice Beckett in 1919 roamed its cliff walks with her painting trolley, and textile artists and sculptors Michael O’Connell and Ella Moody built their ‘Barbizon’ amongst the ti-trees.

His mother was potter-sculptor Joan Macrae (1918–2017) who with resident artist friends, including painter Inez Hutchinson and ceramicist Betty Jennings, staged an exhibition in 1953 which led to their establishing the not-for-profit Beaumaris Art Group later that year, and where later its Joan Macrae Gallery was named after her:

“My mum was a potter and a pottery teacher. We were living in Point Avenue, and like all the streets there at the time it was unmade. I went to Beauie State School and would pass the occasional snake on my journey.

I got involved in art—painting and so forth—in a very creative atmosphere. I’ve even found photos of me at six and seven making sculpture out of old found objects in my mum’s studio where she had her kilns.”

Beaumaris is situated on a peninsula of Port Philip Bay and was then buffered from surrounding suburbs by all the golf courses and tracts of native bush. Point Avenue where the family lived at No.2 was named after ‘The Point’, a Victorian-style mansion overlooking Ricketts Point, demolished in 1959. Residents of the western end of Point Avenue, led by Ian’s father Colin, campaigned to stop Sandringham Council paving the street, themselves taking responsiblity for filling in potholes. Colin became President of the Beaumaris Tree Preservation Society (now the Beaumaris Conservation Society) and he was interested in the important fossils at the Beaumaris Bay Fossil Site. He discovered fossil remains of a significant extinct penguin which were written up in a 1970 paper by a Harvard University palaeontologist, with the species being named after Colin as Pseudaptenodytes macrei.

Incidentally, on the beach side of the Macrae’s at 401 Beach Road lived the grandparents of Richard Franklin’s (1948 – 2007), whom he frequently visited. A drummer with the Pink Finks rock band, formed in 1965 (which later became Daddy Cool), he became a Hollywood film director of Psycho II (1983) and in Australia filmed Hotel Sorrento (1995) and Brilliant Lies (1996).

An article she’d kept that Macrae found after his mother had died noted 96 clubs and societies and organisations in Beaumaris, including three theatre groups, model airplane clubs, sea scouts, the Tree Preservation Society, and the Beaumaris Film Society which Ian joined and where he saw Citizen Kane for the first time, which remains one of the greatest films he has ever seen. His parents attended the Melbourne Film Festival and though admission was restricted to over-eighteens, from age 12 or 13 he could go with them because he was tall enough to get away with it.

“I felt isolated and that I was missing out on stuff, and was very keen to get out of Beaumaris when I could, to live closer to the city. So I got very involved in going to movies, particularly the Melbourne International Film Festival where I’d go and see every single film. At that time, cinemas were limited largely to the Carry On series from England or Westerns from America.

The thing that really struck me was that the Festival showed films not made in the USA or the UK. Seeing films made in Poland or China opened the door in my mind to new ideas about what filmmaking was. The early Fellini films were at the festival and I always found them fascinating, and Bunuel films, like Exterminating Angel, a beautiful movie, or Bertolucci’s The Conformist.

Extraordinary stuff, and when it was on in St Kilda the whole atmosphere was wonderful. You’d go into one of the restaurants in Acland Street for a break and go back to see another film. Often there was a lot of fog around, making it a very mystical, mysterious and atmospheric experience. I’d be totally immersed and everything became like a movie.”

For a period in 1972 he was elected as Director of Melbourne Film Maker’s Co-op and conducted lectures for Australian Teachers of Film Appreciation with Richard Franklin. In 1977 he was elected to the Board of the Australian Film Institute and remained on the Board for four years.

When Macrae started at Prahran College of Technology at eighteen years old he entered a traditional style of art school offering fine art subjects; painting, sculpture, life drawing, and printmaking. Originally it was a two year course after which graduates might move up to RMIT. While he was in second year it was decided that they would expand it into a four year course. The group ahead of Ian’s year moved into the new third and subsequently the fourth years.

Macrae disputes that photography as art developed only as late as the 70s and identifies as a turning point the year 1966, when Lenton Parr, previously Head of Sculpture at RMIT, was appointed Head of Art and Design in a building still being completed when he arrived. As well as fashion and industrial design he introduced photography into the art school when previously it had been offered only at RMIT in a course known for being very technical, for people who wanted to be a forensic, medical or architectural photographer. Macrae remembers that at Prahran;

“…first year was a mix in which you might do sculpture and printmaking, and then you were expected to major into one of those fields as you went along. When Lenton Parr came in you could do two majors—two things that you significantly wanted, perhaps photography and fashion, or photography and sculpture, or sculpture and industrial design. You could even pick two that normally would be regarded as completely opposing, that you wouldn’t necessarily have thought of as being compatible. I was keen to do photography and painting because I knew I wanted to go into film making. Swinburne film course was just starting and I knew Brian Robinson, who was running that area, and he was a really enthusiastic teacher but really didn’t know a lot about the film industry, so I thought that if I stuck with Prahran and did photography and painting, I’d get two sides of filmmaking covered; the photography side and the creative side there. My main concentration was photography because that was the key element in filmmaking.

Employing Paul Cox and Ian McKenzie to teach photography, Lenton Parr with Paul conceived of photography as an art form and a creative endeavour, not just a technical thing to do with the camera. “For me,” says Macrae, “the most significant person in the whole history of photography at Prahran is Paul, because he had this emphatic idea that photography had to be an art form, that had to be creative. Ian McKenzie basically handled the technical side of photography while Paul encouraged the idea that it was a creative field.”

“Ian McKenzie was a professional photographer and I felt he was a teacher with whom I had not much personal contact. I got along with Paul really well. He was quite an extraordinary person, very charismatic and quaint as well, in his own way, wearing sandals with socks, a great friend socially and for years later as well. A creative photographer, he clearly knew we all needed to have some degree of technical knowledge as well as the ability to be creative.

“The last time I saw Paul was at a retrospective of Carol’s work out at Heide after he’d had his liver transplant. He was telling me that he should have died many years before but for his unusual blood group as someone at his age would not normally be given a transplant. He said he was on his way up to Sydney when he got a call to say a liver had become available and he was the only person who could take it because of his particular blood group. He was lucky and he survived for probably ten years after that. He was so really close to dying at that early stage, you know.”

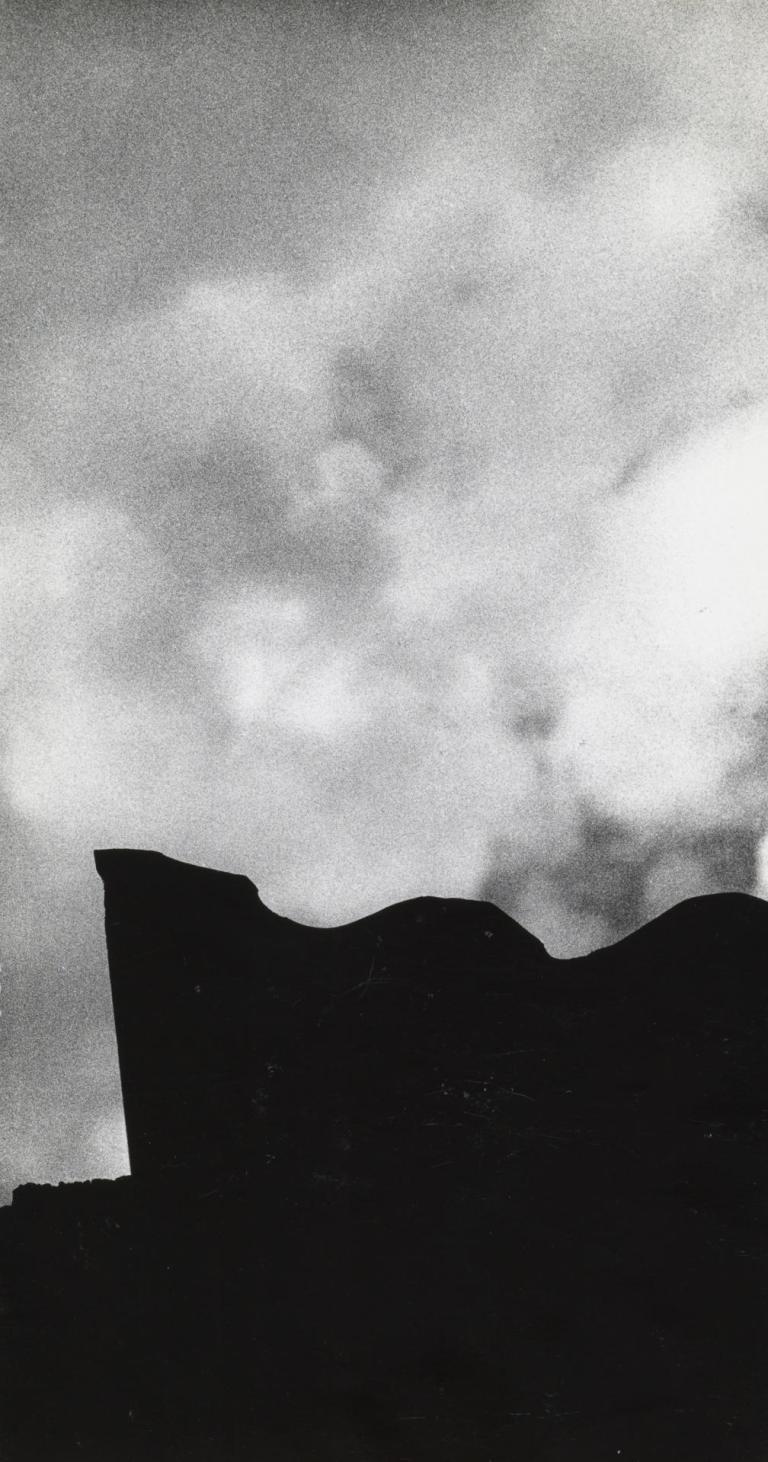

Macrae remembers that the very first exercise that Paul set was to go out and shoot the alphabet, to find photographic images that looked like letters. This taught an approach to photographic composition, to which Carol Jerrems particularly adhered and that Paul stressed, in which “when you took the photo you composed it in camera, you didn’t crop or reshape it later in any way.”

He was there with printmaker Alan Mitelman whom he knew well before they entered art school because they were both connected to the jazz world. Alan played banjo in a band, while Ian played drums and managed The Red Onions.

Among their fellow students were John Scurry (of The Red Onions), Ross Hannaford (of Sons of the Vegetal Mother), and Jim Pattison who was a year ahead. Ian and Jim shared accommodation in an old bakery—just an open space lacking bathroom and kitchen facilities. They took showers at a nearby squash court, and they endured a rough period in terms of living conditions.

Later, he shared a house on High Street with Carol Jerrems, with whom he found a place on Mozart Street in St Kilda, where Robert Ashton joined them. The three of them resided there for several years, looking after Carol due to her personal struggles, but enjoying a friendly relationship. Mozart Street was an interesting, popular place to live; after Carol and Robert left, Ross and Pat Wilson of ‘Daddy Cool’ moved in. Following Ross and Pat’s departure, Greg Macainsh from Skyhooks took up residence. The house was consistently filled with intriguing and creative individuals.

Macrae was interviewed for Girl in a Mirror: A Portrait of Carol Jerrems (2005), and when Natalie King organised the retrospective on Carol at Heide, he was involved and contributed from his significant collection of Carol’s work and letters, which were incorporated into various publications over the years. In the documentary he and Robert are referred to as ‘the nannies’ by the editor who recognised them as Carol’s initial caretakers; “I can sort of see the editors saying, ‘oh, let’s put a bit more nannies in there.’”

Catriona, the subject of Jerrems’ iconic shot with the two punks, was then Macrae’s girlfriend. When Carol visited, Catriona was eager to have some photos taken for her acting pursuits. Carol made a few photos in Mozart Street but the back garden was getting too dark because it faced south. Robert was living in Vale Street so she decided to take everyone there, where the sun was coming in from the north. That’s where Carol convinced Catriona to take her top off.

Carol put herself in danger to take photos so that often Robert and Ian were distraught with worry about her;

“She would just get herself into danger often, but she was dedicated to taking shots, nothing would stop her.”

Asked did he think that ethos was particularly strong amongst the other students during his time at Prahran, Macrae answered;

“I think so. One thing Paul had us do, in parallel with what we were talking about with Carol, was to go out to awkward, interesting places. There were some photos, for example, that I took in a notorious bar in Port Melbourne where all these guys were playing pool. Also I took a number of photos at a gruesome abattoir. We found ourselves able to go out and take photos of people in those sort of environments and get their confidence, and build our own.

There were various photographers, in the world scene, who were out there doing such things. Diane Arbus interested Carol. South African photographer Sam Haskins who used a lot of grain, and Lena Riefenstahl, had styles that influenced her too.”

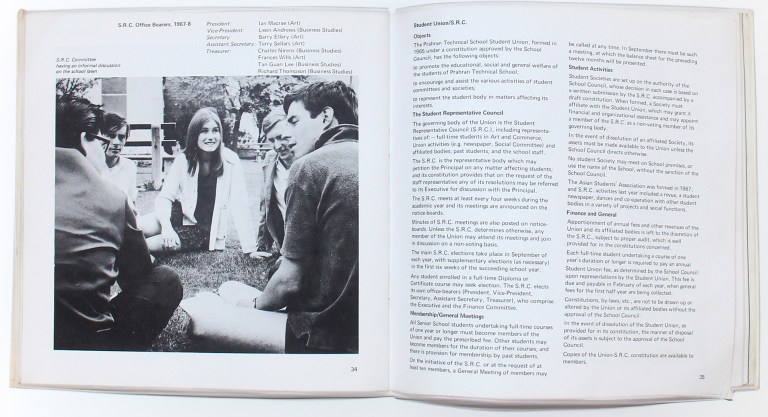

Until about the second year of art school Macrae played drums in the jazz band the Society Syncopators and continued to manage The Red Onions before study demands intensified and managing the band became increasingly challenging. During his time at Prahran, Ian served on the student representative council, eventually becoming president. He remembers that it was Prahran College’s unique dynamic, where the art school held dominance, that allowed them to oversee social aspects of college life. This stood in contrast to Swinburne, where he later lectured, as the art school there was merely a small component of a larger university focused on engineering and other disciplines.

At Prahran, Macrae with other students designed and illustrated the college handbook and organised revues and monthly events, to which everyone brought their own food and supplies. Though these were popular, they faced bans from venues, including the Exhibition Building, compelling them to relocate their events, with the final one being held at Moorabbin Town Hall. Jerrems and McRae, after he graduated, contributed photography to Melbourne University’s Circus

Apart from Paul, Ian McKenzie was the only other photography lecturer and Paul, of course, was making films at the same time. Often students were involved in his various productions;

“I can remember one scene once on the really old train that used to go from St Kilda to the city with the doors that open into compartments. We were just extras, and I can remember Carol being in that.”

Considering how Prahran contributed to his filmmaking, Macrae believes it instilled in him an open, creative attitude. Film directors may emerge from diverse backgrounds, starting as actors perhaps, or in various other fields, before moving on to direct. Ian was particularly engrossed in the photographic aspects of filmmaking, including lensing, composition, lighting, and other elements typically associated with photography. These considerations influenced his collaboration with cinematographers. Initially, he even took on the role of cinematographer and editor for a few projects. However, he soon reached a point where he recognised the expertise of dedicated professionals in these roles and deferred to their skills.

He graduated from Prahran College of Technology Art School in 1968, then with Mark Gillespie he made two short films for the architecture school at Melbourne University for their revue. He and Mark became great friends from that experience and worked on a number of films together. Working for an income as a barman and a waiter at various places, he sent letters to film companies and television stations trying to get some work, perhaps to start as an editor. Crawfords, for example, offered a position as a sound assistant which Macrae didn’t want, before he got an offer from Channel 9 to start work straight away there as a director-producer. He was there for about two years doing all of the billboards—the opening and closing of programs—and doing promos for movies and various programs, with about 20 hours a week in studio.

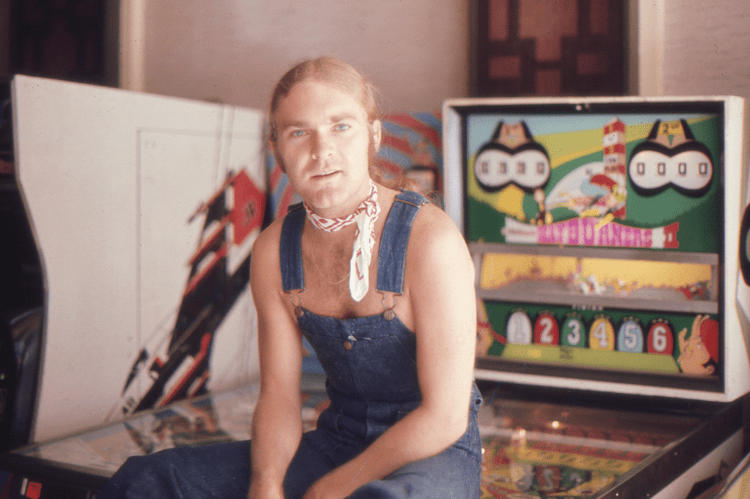

It was a steep learning curve for him because prior to that, he had always handled the shooting himself and had never worked with a crew before. In the first week, he found himself out with a crew, working on Salvation Army promotions, which was a significant leap into the professional world. Then, in 1971, he worked on a program called “Fly Wrinklys Fly,” a rock and roll show which was as a precursor to the iconic Australian pop music TV show, Countdown. The program included bands like Otis Redding, Pink Floyd, Ike & Tina Turner, Daddy Cool, and Billy Thorpe & The Aztecs, alongside segments addressing topical issues. One of these took a stance against the Vietnam War. Despite incorporating controversial elements, the program was well received. In a review following its initial broadcast, The Age newspaper’s television critic John Pinkney, in an article titled ‘The vidiots bubble full of pop,’ praised “Fly Wrinklys Fly.”

“…more interesting than its callow, elder-baiting title might suggest. Garbled and chaotic as static from distant suns, the show spurns such conventions as compere and format. Instead, producers Jim McKay Jun. and Ian McCrae [sic] have created a primordial electronic soup in which embryos of future TV life forms are already visible. Conventional “narrative” television, whether drama, variety, or film, requires from audiences some degree of concentration. FWF, conversely, is a form of radio for the eyes—a background drizzle in Australia’s intensifying monsoon of media. And such drizzles are likely to become commoner, when cassettes are widely marketed. TV networks—like radio stations before them—may find that to hold the viewer, they must make lighter demands on his attention. The rudderless Wrinklys, with its pixilation, Rorschach-blotted images and eccentric camera work straight from a mushroom dream, spoke disorienting volumes for its crew’s skill.”

He was working with Frank Packer’s son Clive, who managed the television division while his brother oversaw the newspapers and magazines.

“Well when Frank Packer saw what we had done with our program he hit the roof and canned the show after only two had gone to air. We had two more ready to go down, but we were allowed only to have one more episode. We combined the best of those, so got only three to air. Clive Packer and I resigned over that. It was really a big thing for Clive Packer because he was resigning from his father’s business and subsequently moved to America where he lived from then on.”

Looking back, in her article ‘What рор needs is pep’ in The Age of 4 January 1972, Wendy Milsom was pessimistic about the pop scene and its prospects for 1972 and remarked that:

“Pop television looked hopeful less than a month ago when Fly Wrinklys Fly started on GTV-9. A slick, well-produced show featuring local artists live, it was quashed by the network before it had a chance to become established.”

Macrae recalls taping “Great Balls of Fire” with accompanying footage of atomic bombs and explosions throughout. Hair was a contentious topic, with individuals sporting long hair often facing abuse in public. Carol, with her wild hair, featured prominently in the program. The content was abstract and controversial, garnering attention from newspapers, with one even labelling it a masterpiece, much to his surprise. The uniqueness and radical departure from conventional norms contributed to its acclaim, setting it apart from anything else.

Ian Macrae Fly Wrinklys Fly segment on hair (1971) and Qantas cinema ad (1972) featuring Carol Jerrems and early computer video graphics via Vimeo.

After Ian finished at Channel 9, Lionel Hunt of the young creative advertising consultancy Campaign Palace approached him, having seen “Fly Wrinklys Fly” and showed him a booklet they had made to encourage young people to fly on Qantas. It was called ‘The How, Why, When and Where of Here, There and Everywhere’, and they asked him to make it into a two-minute cinema commercial. That was the brief—nothing more than that, and he had never shot colour, nor had he ever shot 35mm. He then interpreted the brochure, involving many of his friends in the process. In one scene, Carol is in a rowboat out on Port Philip Bay. The commercial won numerous awards for him, including an AFI. It set him in motion, and next, he was asked to be involved in Tommy, the rock opera to be performed at the Myer Music Bowl.

Ian Macrae (1973) Graham Bell in Tommy

For Tommy, he employed innovative visual elements, multiple screens and projections.

“Behind the orchestra, singers and the choir, I placed nine screens, a big one in the centre and four on either side and 37 projectors illuminating the back of them. With a motor drive I took hundreds, maybe a thousand, images of the different singers and performers so that a series I’d shot of say, Keith Moon, were like freeze frames from a film. We showed that Melbourne and Sydney, and back in Melbourne again.”

From there, Macrae had a period of years during which he went back and forth to New York. When Australian television began broadcasting in colour, Campaign Palace was handling the promotion for Channel 7, and he was tasked with creating all the billboards announcing the advent of colour. Originally meaning to do it in Melbourne at AAV, he discovered that equipment he was to use, the CMX 600 RAVE (Random Access Video Editor), the first computer-powered non-linear video-editing suite capable of creating patterns and 3D shapes from letters, did not arrive. He had to travel to New York to use one there. The deadline for the launch of colour was imminent, and he found himself working on it at four in the morning due to the equipment availability. With about 40 different pieces of film, each with its own requirements, he hastily compiled the video tape, flew to Los Angeles, and sent it via satellite back to Melbourne to Channel 7. Just in the knick of the time.

Comparing the shift from black and white to colour in television, Macrae considers it happened much as it did everywhere else in the world so; “it was a fairly straightforward transition and didn’t really alter too much in the way you filmed because you just ended up with a colour print rather than a black and white print.”

Digital, on the other hand, Ian thinks is revolutionary and he enjoys shooting in that medium. Before, using 35mm film they would have a choice of 400 foot rolls or a thousand feet which would last for 4 or 10 minutes. They’d be filming and the camera assistant would say when they were about to run out. They could be right in the middle of something they were doing, with the acting in full swing, but they’d have to stop, wait for the reload, check the gate and so forth. Crews now can shoot digital for hours, depending on the size of their drive storage, so it doesn’t entail such delays and interruption.

“That’s good, but it’s also bad” says Macrae. Jill Bilcock, an editor who worked with their editor Mike Reed, and who went on to make major feature films and who won an Academy Award, says that the problem now is that people just shoot too much. Instead of having 3 or 4 takes of one scenes she’d have 30 or 40 takes, because when they were shooting film, they were conscious of the thousands of dollars that were going through the camera every time they pressed the button, where with digital, there’s fewer costs apart from crew time. Bilcock complains that some directors are not decisive about what takes they want to use. Thus there is a negative side of this new medium, but Macrae is otherwise impressed:

“I look at our television now and it’s so crisp and sharp and the detail’s there. When we shot 35 we would end up that quality of image, but then it would go into analogue, into people’s homes, and look like shit! Now, if you shoot digital, you know that what everyone at home or in a cinema will see is exactly as you shot it.

The other thing too is that you were always bound by the ASA level of film stock you were using, so if you wanted to shoot at, say, f5.6 or f8 you had to put a hell of a lot of light in there whereas with digital you can virtually shoot with no light at all, so the budget for lighting is dramatically less than it used to be.”

Macrae feels the Prahran experience which required adaptability prepared him for such challenges and changes:

Because I got myself involved in diverse things within the college like the revues and publications, while managing a band for which we used to do screen printing for posters and publicity, and as president of the SRC dealing with the college council and issues to do with students, that was an enormous range of experience I had there that really helped me for the rest of my life. It was a mixture of management, of creativity, of being outlandish.

From 1972 to 1978 he had moved into directing commercials, and in 1979 he and his partner Andrea Way setup their own busy production company Macrae and Way Film Production, producing more than 2,000 commercials, short films and documentaries, and winning almost all major awards in the field. The bulk of the work was high-end ads for television and involved working in Hong Kong and, and Thailand and other parts of Asia and all over Australia. In the last 15 years he used a lot of extreme visual trickery; “I was the master of using green screen and blue screen and, and mixing in computer generated imagery with 35mm film.”

Macrae had always wanted to get back into photography. The challenge with filmmaking, he found, was that it always involved collaboration and compromise, considering various elements such as actors’ performances and cinematography in changing weather conditions. He yearned to pursue a more personal endeavour where he could work independently. In the late 90s, he held a retrospective exhibition at Artistcare Gallery, and afterward, he and his partner decided to scale back their business and take a break.

They spent a year living and traveling in Italy. Upon returning to Melbourne, they chose not to reopen their production company. For about six years, Ian directed commercials on a freelance basis. Now, he is more focused on photography than filmmaking. He has held three exhibitions, self-published ten books, and derives great pleasure from the creative process.

Ian did everything except feature films and he started considering the idea of making one. He collaborated with a couple of writers to develop a script, but never reached a point where he was fully satisfied with it. As the script evolved, the cost of producing a feature film escalated, which led him to reconsider. He doesn’t view it as a regret; rather, he acknowledges that filmmaking is a distinct field requiring exceptional writing skills, something he doesn’t possess. He reflects on the challenges faced even by seasoned professional directors who often struggle to assemble a cast and secure funding for their projects. He recounts a story about Fred Schepisi’s tribulations, in which a delay with one actor led to complications with the entire cast and the withdrawal of the financial backers, illustrating the precarious nature of film production that Paul Cox also faced;

Paul never really had commercial success and was always struggling to get the money together. A lot of people on his films worked either for nothing or minimal rates and he nearly always shot 16mm, although he did shoot a few in 35mm. He was economical. Now every so often I’m helping young filmmakers to make a film and of course they’re now shooting digitally which makes a huge difference to their budget. You can shoot a movie on an iPhone.

Though Ian has kept 35mm equipment, the dust on their boxes is a testament to the protean nature of filmmaking. One project he never completed was Freya, about a fox that becomes human. They initially believed they could train a fox to perform rather complex actions, which proved unachievable in the end, and the project cost heaps out of their own pockets. The crew filmed in rural areas using 16mm equipment, while Jill Bilcock edited the footage. Despite her expertise, they couldn’t salvage the project. He speculates that nowadays they would easily succeed with digital imaging and realistic computer-generated animation.

Ian Macrae’s career trajectory, starting out with his box brownie and doing trick photography, gains exponentially as the strength of his work develops from his ability to work with green screen and other technology, and a devotion to the idea of the image being the most important aspect of filmmaking.

11 thoughts on “The Alumni: Ian Macrae”