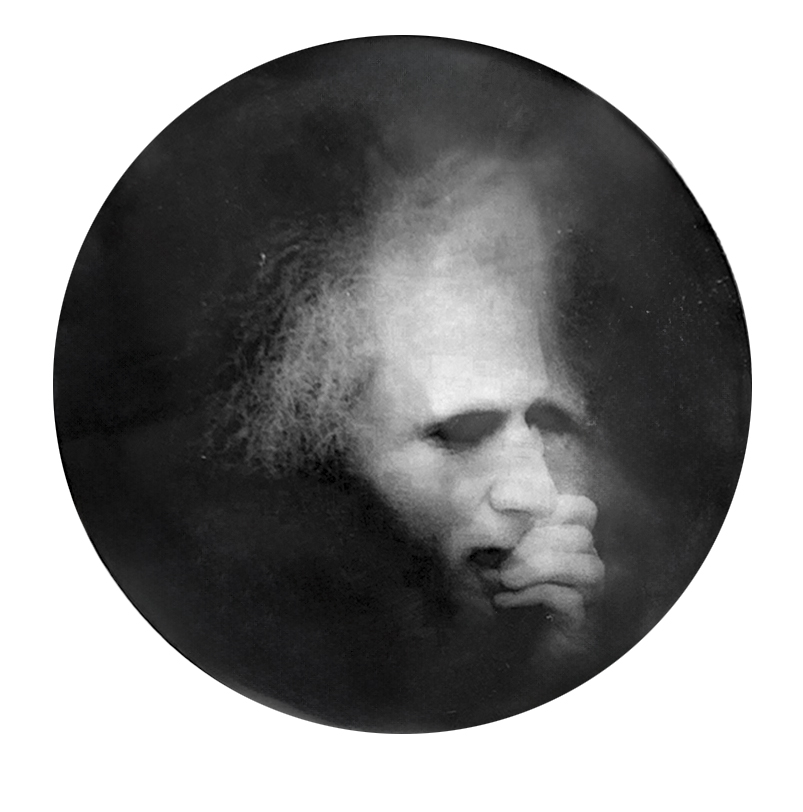

Stephen Wickham remembers…

Gordon De Lisle got me in, Paul Cox got me out…Prahran. 1972.

To everyone’s great relief I left Camberwell High School after repeating Year 10. No interest in school at all, home life not so good, too much time ice-skating at St Kilda’s famous St Moritz–doing all the right things with all the wrong people. Serious trouble everywhere.

I needed to get away. Safely. The Sapphire Coast Express delivered me to Merimbula.

Darrel was there. We had done round-one of my two shots at Year 10 together. We were wayward loyal friends. He was big, gentle; a budding dope-dealer and many years later he graduated to stolen opals etc, etc. High times with dangerous twists and turns.

It was not romantic: we worked hard, got sunburnt, heart-broken and moved between the South-East Coast, Melbourne and Adelaide. Buses and trains. Hitching? Not really, as we looked bad.

I went home and my parents were uncertain. A scattered time, an apprenticeship I quit, odd bad jobs, petty crimes and stupidity. More illicit behaviour with older friends at Monash and La Trobe University. Economics and Politics. Marcuse, Max and Mao. Zimmerman.

My brother in-law had a good home-built darkroom. Kindly he let me use it. I did.

Yes, a true-blue ingenu. In late 1969, I walked off the street into the Department of Photography at RMIT unannounced with a folder of photographs under my arm. Somehow, I had a conversation with the Head of the Department. He was generous and said the work was ok. He told me if I did Year 11 and came back with a good pass and better folio, I would be offered entry in to the School of Photography… Back to an all-boys high school I went. Sharp grey suit, shiny black shoes and the commitment I made to the Principal.

Box Hill High School was one of the few places that enrolled mature-age students. Mum and Dad were great, and I studied with purposeful clarity. The teachers were excellent. The marks were good and on the evening of 28th September 1970 I won the National Service Lottery. Happy 20th birthday. Just a quiet night with Frank and Shirl. Fuck me! Really?

All the way with LBJ. Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh, the NLF is gonna win!

Twenty years of age and called up for National Service. I had two and a half months to finish what I started. A deeply confusing and very difficult time–people in my position were going to gaol. I hadn’t attended the Medical and was submitting a notice of conscientious objection and applying for a temporary study deferment. Not a pacifist and at high school. Life was scary.

Dad and I walked into the Commonwealth Centre, on the corner of Spring and Latrobe Street, Melbourne. Two smart-arses with two forms and a shitty Plan B. It was simply terrifying.

The poor bloke at the window took both and stamped them. We walked out. Shock and awe.

Not even Jim Cairns could tell us what to do. Was I technically AWOL?

I had been looking forward to the interview at RMIT. Now the stakes were a lot higher.

They were pleased with my folio but said that I had to have Matriculation. It was deeply concerning, and I explained to them that the Head of Department had previously given me his word. That made no difference. I walked out onto Swanston Street dazed and confused. Panic and chaos conflated, and hanging tough I was not. Keep on trucking. Sure.

The year was ending; my panic rising and somehow, I am on the phone with Gordon De Lisle. He informed me that there were no positions available at Prahran Photography, as interviews were over and finalized, he also told me that the Prahran Foundation Year had already completed their intake.

He and I had a long conversation about my family history and what I hoped to do in the future. I had no intention of doing National Service. My best memory is that Gordon said that I should ring him early in the new year of 1971, he made it clear that he didn’t know what he could do to help. Neither did anyone else.

Across his card table Jim Cairns said “Canada, North Viet Nam, Libya or Morocco?”. He had a regular spot outside Coles in Burke Road Camberwell, every Saturday morning.

I have no memory of summer ‘70–‘71. The Endless Summer. Not!

I spoke with Gordon De Lisle in February 1971. Another long conversation in his office. At some point he picked up the phone, called Brighton Technical School and spoke to the head of the Art Department. He explained my circumstances and they told him that there were no positions available. Mr. De Lisle said, “…this young man needs a place, make one for him…”.

Prahran Institute were responsible for the accreditation of the Brighton TOP Art Course.

Sort of on-the-run, out of my depth, and seriously underprepared. My nerves were shot to shit. My grandmother’s Russian-Jewish doctor prescribed anti-depressants. Lobotomy, sure?

Mum suggested I just go and get it over and done with. Years in a Military Stockade, hmmm!

Beyond relief, I walked into an English class at Brighton Tech. In a Joseph Saba suit, hand-made shirt by Atelier, big hair and clueless. I cannot remember the shoes. The course started weeks earlier. Ms. Sue Hallas: “Bambi, sit”.

My father was building a new garage-workshop, he made part of it a wonderful dark-room.

After a feverish and exciting year at Brighton where the coursework was the most important thing in my life, I passed and applied to the Photography Course at Prahran Institute.

The YES letter. Surprised, the emphatic delight. Bang a gong (get it on), ohhhh.

Dad took me to lunch at Vlado’s in Richmond. I was a vegetarian. The sausage was great.

MY YEAR AT PRAHRAN.

I arrived at Prahran, with a borrowed Pentax K1000, with the standard, 50mm lens.

My lifelong friend Gary Shirley got me a duty-free Mamiya C330 on a family holiday to Fiji.

Concerned, crazed and curious. Was I good-to-go? Well, let’s just see about that.

Loose as a loon, living on and off at Auburn Road Hawthorn, drug-fiends, Swinburne film-school students, and nefarious yippy-trippers, hard-assed anti-war Mofos, full-face Bell helmets, black leather jackets and more confusion, fear, art, cameras. Ducati 250 single? I wish. I still can’t remember where I was living for most of that year.

Nothing was settled, a movable feast, a progressive dinner dance of bad dreams, riots of fantasy friends and shape shifters, all at F-64 on a clear bright day. Good luck with all of that.

And here I was at Prahran, studying photography. I was not cool, a little too intense, a wee bit fucked up. Not off the hook. Their war was still killing people. Did they still want my help?

The most exciting subjects were art-history, sociology, and psychology.

David Graham Cooper. David Émile Durkheim. Ronald David Laing.

Photography itself, was a mix of the technical, aesthetic, and Paul Cox’s poetics and philosophical views of the universe. I found the technical information very helpful, very useful, and worked hard to understand and integrate the practical with the visuals.

I was a novice at it all. The assignment work I found baffling, sometimes pointless, and very limiting. I am bad with guidelines, not good with being told what to do. How to do? – sure happy to listen.

People I admired did the assignments with flair and skill. I was getting over the line and read Langford’s Basic Photography, The Ilford Manual of Photography and asked questions.

Just getting by, nothing good. Sorting myself out, still shocked and angry about the Call Up.

The Fog of War. The Mists of Time. Desolation Row.

At Prahran we all took a minor subject. I took printmaking as it was conveniently across the hall in the basement and painting was full up. My friend Gary ‘Spook’ James, and Luigi Fusinato were studying printmaking. We were close friends from Brighton Tech and went to many of Sandra and Ken Leveson’s parties. Ken taught ceramics at Brighton. Many weekends we helped rebuild their country house. Art and life and Love’s labour’s lost.

Sandra was teaching printmaking at Prahran and most of the staff from Brighton Tech also went to those 23 Tennyson Street parties. Wild days indeed. Many lines were crossed in the buzz and blurred boundaries. It was great. Conventional it was not. Savage Bohemia.

The Levesons were close to Paul Cox and all the Prahran staff. The open house meant the denizens of the art world were there in full flight and unguarded.

I failed my printmaking minor. Got great marks in my academic subjects. Photographs?

Years later, I taught Printmaking at the Victorian College of the Arts for Undergraduates and Post Graduates. I remained friends with Ken and later his brother Neil.

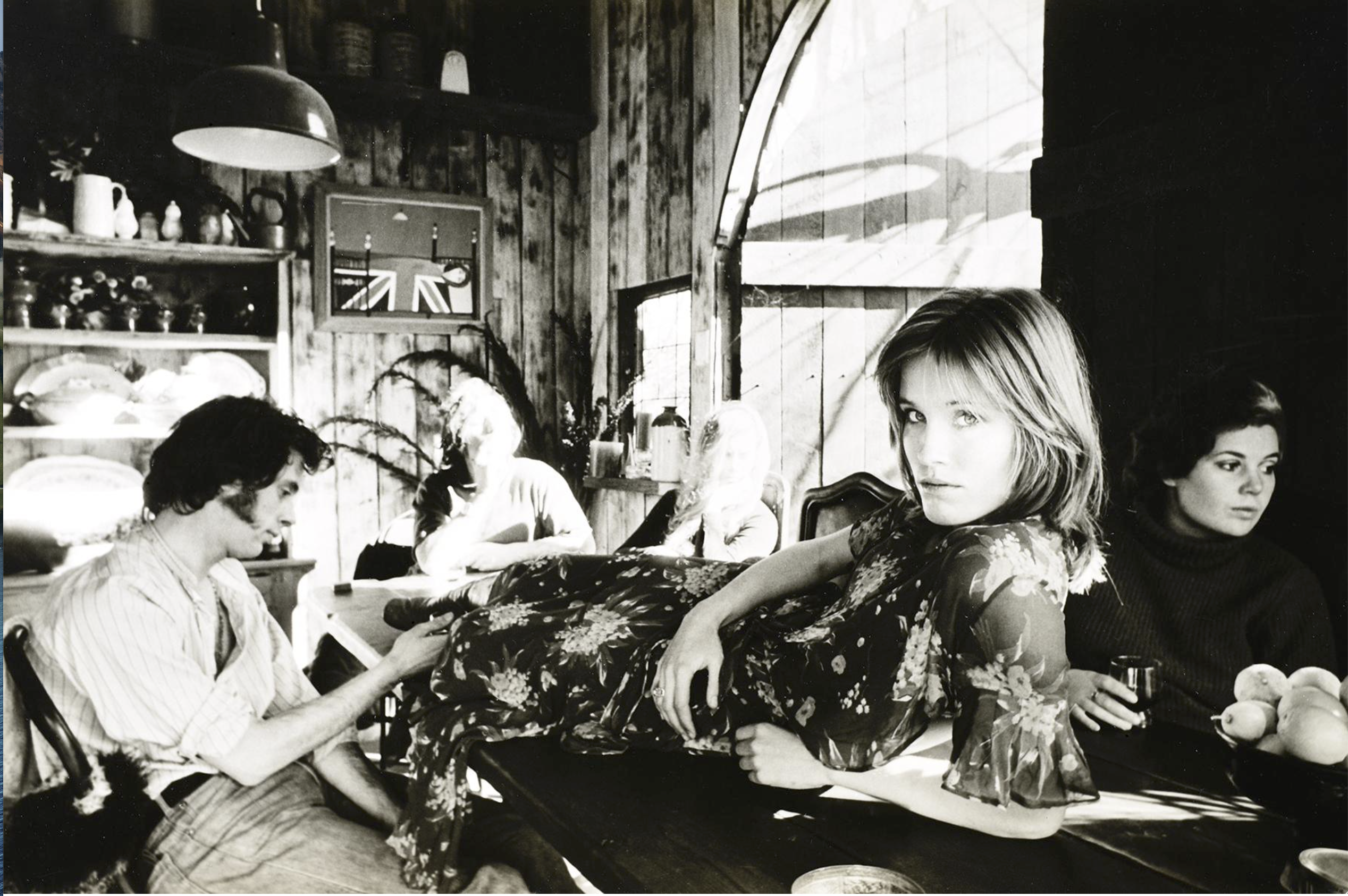

The photographs that I made at Prahran were largely a reworking of ‘pictorialism’ and attempts at informal portraiture. Street photography was an anathema to me. I didn’t have any personal interest or affinity with American Modernist Photography. I think I got it, but it wasn’t for me. This sounds bad, but there it is. Europe… always Europe, the charnel house of history and empires.

Suburban Prahran was not so new to me. My very early childhood was spent in St Kilda, South Melbourne and later Brighton. Most of my extended family got out of Vienna in mid-1938. Jewish refugees. Cosmopolitan, integrated and then in exile. Safe in Australia.

Whatever was exotic about inner Melbourne was being absorbed and processed–in the Acland Street restaurants and cake shops, delicatessens and coffee houses. The words and look of post-war Jewish-Refugees. This informed my childhood and early teenage years. The rough-side of St Kilda was my playground and finishing school. Scary tensions and cheap company.

I was constantly at St Moritz skating, every weekend, all weekend. School days saw me on the trams and trains heading to St Kilda. Tube skates and small change for the pay phones.

I’d seen, observed and half-lived amongst numerous layers, fabrics and textures of inner-Melbourne. I didn’t want to photograph it, I just wanted to be in it. This isn’t to say that I wasn’t mightily impressed by the work of my fellow students and the lecturers. Yet it was somehow very far away from me. I had to go. No time to waste.

The whole time I was making photographs, studying, and trying to make better pictures, I was also painting in a bedroom studio. My emotional well-being was not helped by the LSD, mushrooms, cannabis, and (lets-not-mention) the black hash. An overwhelming memory of Prahran days was sitting on the top of the steps looking down into High Street so stoned, I couldn’t get up. De rigueur for the day. Prahran was over for me. It was fabulous.

The end of the year was approaching fast. My stamina and interest in photography had me leaning into painting and an idea to go to the VCA. I travelled to Sydney and, from memory, missed the end-of-year theory test. A conversation with Paul Cox on my return saw me get a pass in photography … on the understanding that I didn’t come back. It was a very difficult decision because the Prahran Year gave me insights and understandings that were unobtainable elsewhere. It had saved me and sorted me out.

At the end of 1971, I was interviewed by Lenton Parr, the Dean of VCA. They had a place in Second Year Painting for me. I took it. A very happy day for me.

The perversity of this circumstance. While at Prahran I was painting but officially studying photography, and at VCA I was studying painting but doing a lot of photography in my own home darkroom. Prospect Hill Road, Camberwell, I think.

I can’t remember when I got the letter from the Commonwealth Government accepting my temporary deferment of national service but I think it was during 1971. The Labor Party won the election in 1972 and Conscription ended.

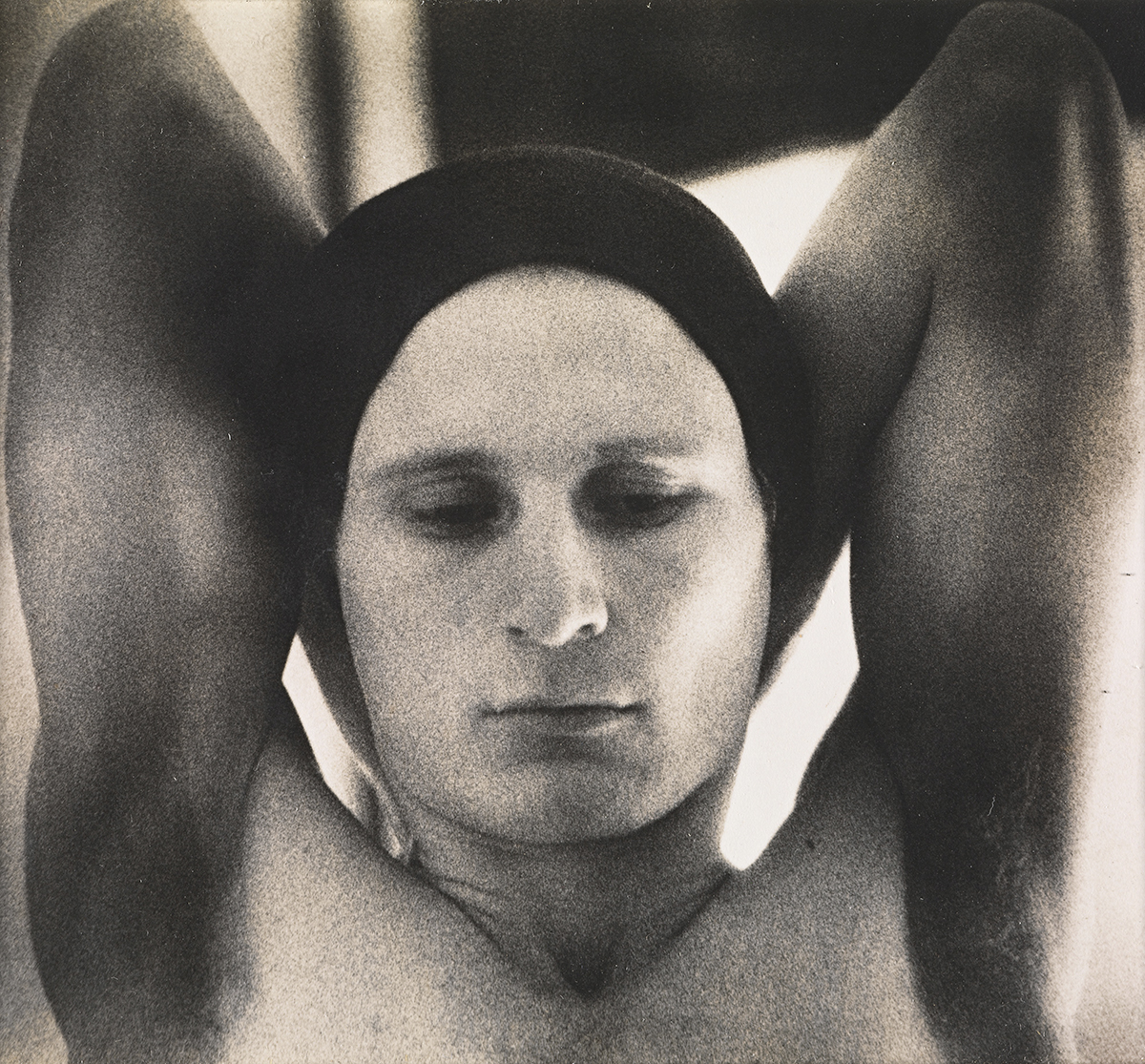

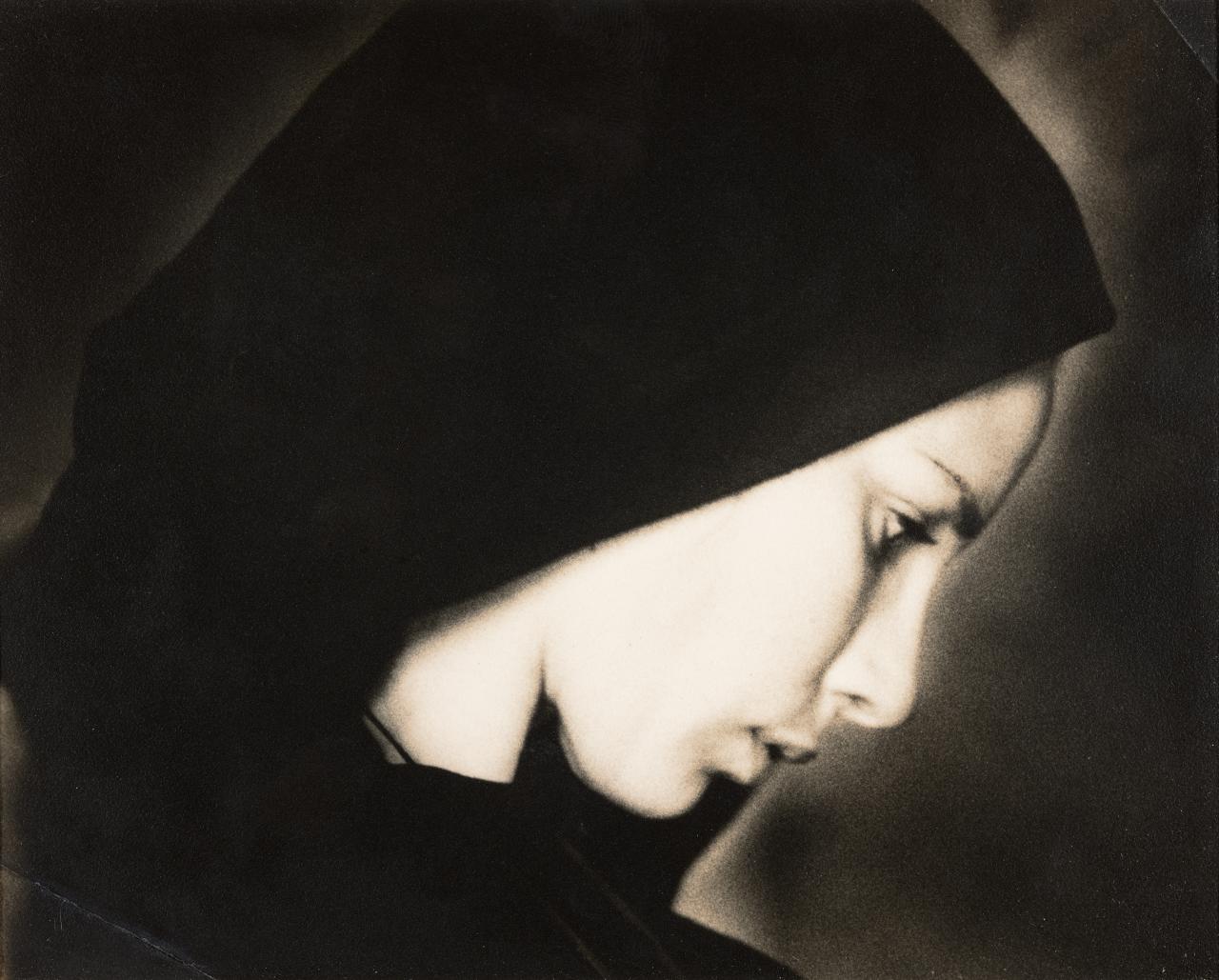

The wonderful Jon Conte was the student who gave me the best photographic technical advice I’ve ever had, and I never thanked him enough. Thanks to Jon, the portraits that the NGV acquired in 1974 were all produced from negatives on KODAK Recording Film 2475, processed in DK50, with the twisting-tumble-agitation-intervals recommended by Jon himself. Thank you.

Paul Cox was a considerable influence on me. His blunt Dutch manner, the overt European aesthetic and his view of the world, made a lot of sense to me. My family was inherently European in their views – politics and aesthetic. I didn’t connect with many other staff at Prahran but I could see the great value of their teaching.

Gordon De Lisle got me in to Prahran, and out of serious strife.

Paul Cox got me out of Prahran, and into photography.

Late December 1972, smoking the endless pipe with feet on his table, Paul Cox said,

“… make photographs a vocation, not your profession.”

Thank you, Prahran.

Wickham made his debut as an artistic photographer at the National Gallery of Victoria when he won its 1974 Special Jury Prize for Portraiture and in the 1975 show Recent Acquisitions when three of his portraits, made on the Kodak Recording Film recommended to him by fellow student Jon Conte, were purchased for the Kodak Collection. Kodak’s data sheet for his film stock notes its characteristics:

“…high-speed, coarse-grain panchromatic film with extended red sensitivity for use in 35 mm cameras. It is intended for photography in low levels of existing light or when very fast shutter speeds coupled with small apertures must be used…especially useful for indoor sports photography, available-light press photography, surveillance photography…Size Available: 135-36 magazines and 35 mm long rolls (perforated). Speed: ISO 1000 to 7000”

A sensitivity considered astounding before the advent of digital imaging was useful but the pronounced grain helped Wickham to emulate acquaint effects much admired in the printmaking that he had also adopted. He used the rather unpredictable hypo-alum toner to supply a warm sepia to the prints, but it is the film’s emulsion’s red-sensitivity that we see working in the bleached, anaemic skin-tones that reinforce a poetic Pre-Raphaelitism as much as do their titles, which Jennie Boddington, first curator of photography in an Australian public gallery, was to declare “agonised.”

On the recommendation of lecturer Alan Mitelman she purchased Wickham’s portraits for the NGV and showed them in her 1976 Modern Australian photographs, among the illustrious company of Geoff Beeche, Anthony Browell, John Cato, Max Dupain, Sue Ford, Val Forman, Les Gray, Fiona Hall, Marion Hardman, Richard Harris, Melanie Le Guay, Shane McCarthy, Euan McGillivray, Grant Mudford, Geoff Parr, Bob Rhodes, Kurt Schwabauer, Roger Scott, Duncan Wade, John Walsh and John Williams.

For a year in 1977 Wickham travelled in Nepal, India, Europe, and then took up a position in 1981 as tutor in photography Caulfield Institute of T.A.F.E. while qualifying with a Diploma of Education at Melbourne State College of Education.

Following the 1979 NGV show Selected Works from The Mitchell Endowment and two group shows in Adelaide, Wickham had produced a new body of work that was displayed in Boddington’s survey from the collection, Landscape Australia at the NGV 6 November 1981 – 28 February 1982. Showcasing the diversity of styles and perspectives that emerged from Australia in 1981 Jennie Boddington’s selection of exhibitors aimed to move the medium beyond the idealised pictorial landscape. In the exhibition catalogue she wrote:

“Richard Woldendorp’s aerial pictures’ precise details of geographical observation related artistically to tales of creation […] Laurie Wilson’s monochrome prints of landscape were reworked during his final years when he was unable to go out with a camera concern the mysteries of death and evoke a sense of finality and raw disgust at the mess humans make upon the earth […] Greek-born photographer, Tommy Psomotragos, brought a fresh perspective to the Australian landscape through extreme close-ups that revealed the energy of growth; a daring visual approach that did not rely on manipulation or tricks […] Mark Johnson’s portrayals of Sydney’s waterfront are severe and eschew romantic lighting and atmospheric effects to capture the boom and bust of Sydney’s past and present as a document of Sydney’s growth over two centuries.”

Discussion around that exhibition and of Wickham’s works in subsequent shows provides contemporaneous perceptions of the status of photography as art in the new decade.

Wickham’s approach stands out for its informality, affection, and use of instant film. Unlike the aerial views of Richard Woldendorp he works in an intimate proximity to his subject, Mt. Buffalo National Park over its four seasons. Delicate, immediate and spontaneous colour images are presented in small gold frames as monuments in miniature. Boddington invites viewers to appreciate them as a poetic connection to, and love for, the landscape aside from conceptual thinking or intellectualisation, which in a following paragraph she decries:

“Wickham is a teacher and a product of our art training system [so] inclined to intellectualise or to theorise about visuals and this sometimes has the effect of chasing the meaning away […] Conversely […] the photographs are made with a simple foolproof camera. So it is a set of innocent views…arising from a complex net of theories and even to be explained by art jargon. I […] suggest that these preceptive and evocative visuals have a quality which owes nothing to Wickham’s didactic tendencies, however intelligent[…] and that they would look just as good in a personal album, to be thumbed through with pleasure. They need to be savoured for what they are, delicate and stringent pictures of a landscape the author knows and loves. They are visuals arising rather more from poetic appreciation than from conceptual thinking and they are a cogent argument for the language of photography best enjoyed without the language of words.”

Reviewing the show in The Age on 17 February 1982 not long before it closed, Geoff Strong, who attended Prahran five years after Wickham, frames Landscape Australia as a foil to the dominance in landscape photography of the Americans:

“…it is good to see a portfolio of contemporary work which owes nothing to the “purified print” inspired by Ansell [sic] Adams and the “zone system’ […] propagated with the kind of one-eyed zeal akin to deep south Christian fundamentalism and which almost deserves an export award from the US Government. What it seeks to do is produce an image of such tonal depth that it seduces the viewer’s eye with its richness. Its protagonists say it can be used for any sort of photography, once mastered. In practice it tends to be so cumbersome that most of the images produced are of rocks, trees or buildings (the only things that will stay still long enough).”

Selectively applying the term ‘artist’ in reference to the exhibiting photographers, Strong compares Woldendorp’s pictures to Pioneer and Voyager space craft images as providing novel views of a physical world rather than any insights into the mind of the artist as, he writes, does Stephen Wickham in…

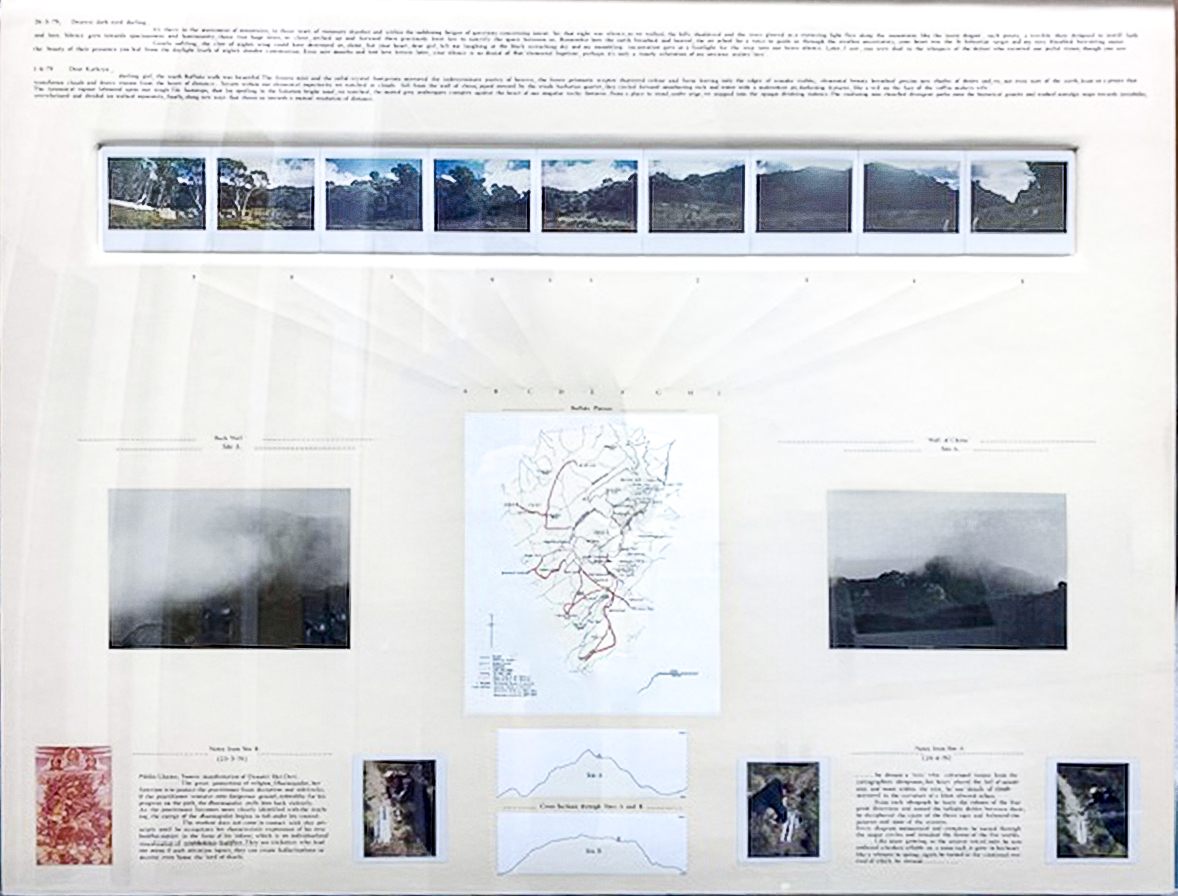

“…instant camera pictures mounted on an elaborate map of the Mount Buffalo National Park and accompanied by a text which includes quotes from the Tantric scriptures, apparent love letters and other mumbo-jumbo. The intention of his work, which centres on a “magic” ring, is to define a kind or ritual and relate it to himself in the wilderness.” Strong concludes; “I hope he enjoyed his time in the bush.”

That year, 1982, Wickham held his first solo show Sites for A Contemporary Ritual at the Queensland College of Arts.

In March 1983, Boddington recommended for purchase nine of Wickham’s works. She prefaces her report in writing that Stephen graduated from the Victorian College of the Arts painting in 1974 and won the Hugh Ramsay Prize in 1973, that his work was in mixed media and increasingly included photography, that his small colour photographs shown in Landscape, Australia had been purchased and asks the Gallery to consider purchase of black and white prints made in Mount Buffalo National Park:

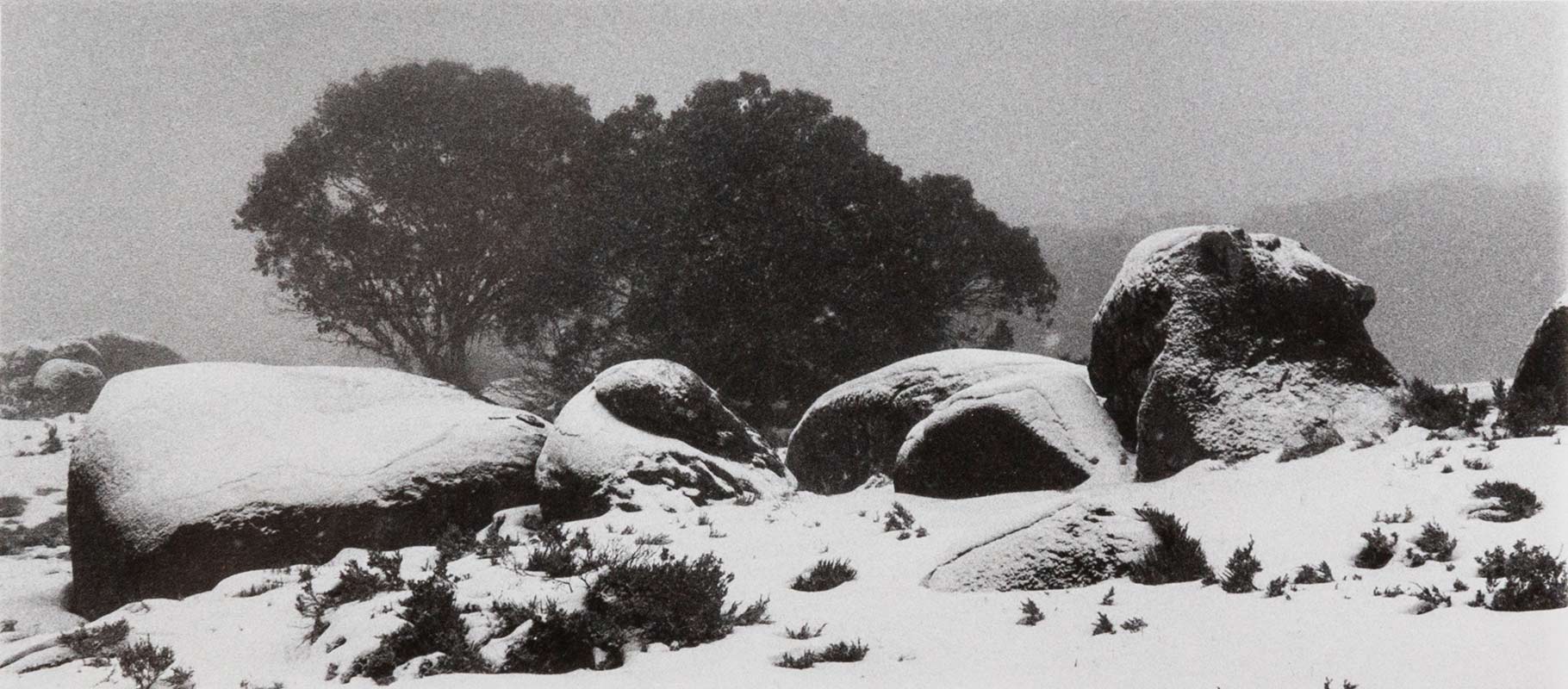

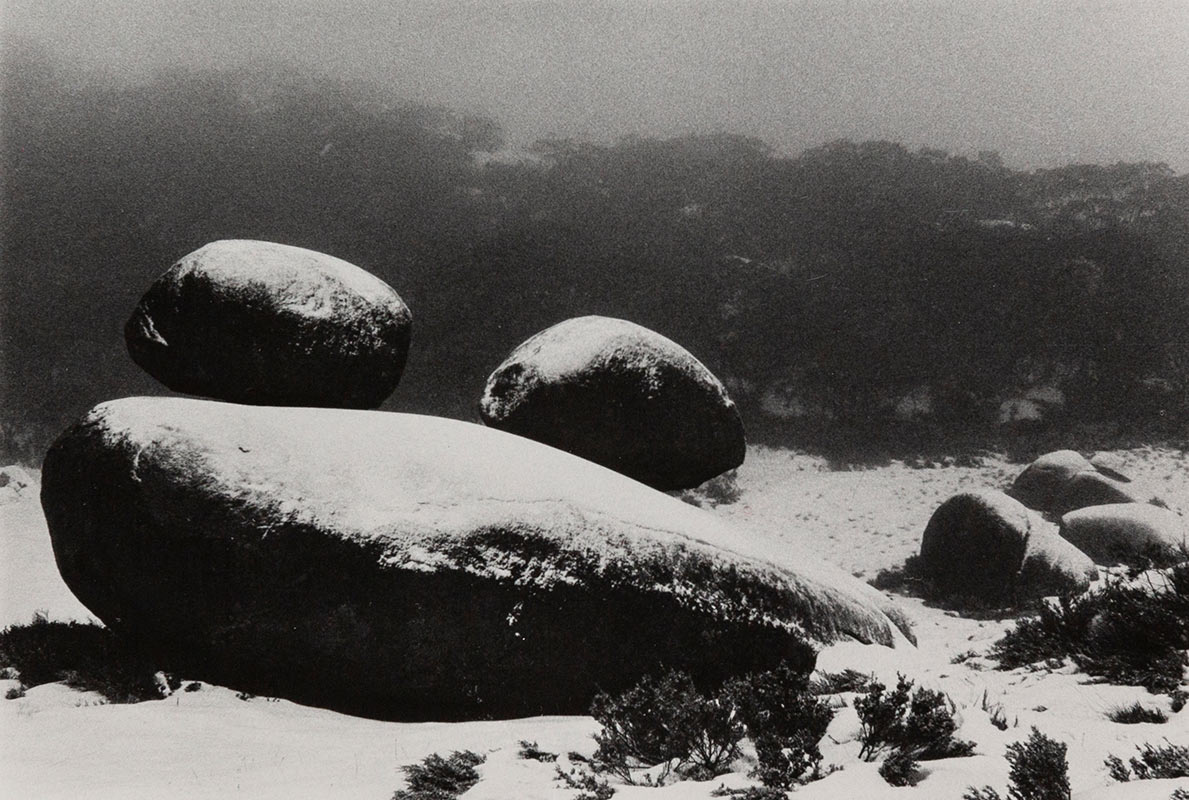

In these 9 pictures the artist has produced a lyrical song of winter: the cold and silence are intense; the presence of rocks, some rounded and others anvil or seal shaped, outlined with snow, sometimes in sharp geometric relief and sometimes obscured by mist or snowfall, has a strange quality not unlike the spirit feeling haunting the ancient sites where rocks have been placed by man for religious purposes. These of course have not. They have probably never been moved but lie where they were formed and weathered in ageless geological time. Stephen Wickham has produced in these images a poem which is perfectly compounded of an intense emotional response and the intellectual process of how to express and convey that response. Each picture is perfectly ordered unto itself, but added together the group is a delicate orchestration of parts, the shapes and tones bringing to the viewer an experience of place and season that is truly satisfying.

Like Strong, she goes on to distinguish Wickham’s landscape imagery from the predominant American style:

The work is subtle and unusually poetic for its period. Nearly all celebratory landscape work at present done in Australla is moulded in the West Coast American tradition. These photographs are original and have been made with intelligence. I recommend that the purchase be approved.

She then wrote an essay for his second solo exhibition at Visibility Gallery, Carlton, of a continuation of the series, part of which was displayed prominently in the Art Almanac listings as a profile.

Beatrice Faust, reviewing the show in an article ‘Landscape Art Flourishes In The Wilderness’, in The Age, 20 June 1984, is complimentary but uncomprehending. She lumps Wickham in with pictorialist “notables like Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter, and Olegas Truchanas”. While wasting words on description she hints at some ‘message’ being being surreptitiously conveyed “in the most delicate and amiable way,” and without using texts “to spell out impassioned but garbled comments on his scenes,” nowhere is it made clear what that meaning, nor what its heuristic might be.

For Kris Hemensley, writing in the Spring 1984 edition of Photofile, Faust’s recasting of Boddington’s opinion that the Visibility Gallery show was an advance because it did away with “the crutches of poetic texts” was mere prejudice. He declares that “Wickham is artist enough to elude that deadening conformity.”

“His 1980/81 representation in the National Gallery’s landscape show, his gold-framed colour snaps, proposed a complex strata: an interleaving of what is seen, who is seeing, and what it is comes through of that conjunction.”

In Art and Australia of Summer 1988, Charles Green notes how during the 1970s Wickham paintings incorporated photographs and found objects;

“They were distinguished by hermeticism and a highly literary, studied fixation on images of pain, loss and suffering. Ophelia, 1977, acrylic on jigsaw puzzle, was typical of these works. A psychedelic maze of colours, not unlike snakes-and-ladders, partly overlay the kitsch jigsaw puzzle replica of Miilais’s Ophelia that the artist had acquired at the Tate Gallery.”

Engaging with ideas around that bicentennial year of Australia, Green considers that given Wickham’s deliberate abandonment of meticulous photographic control in 1978 ( when Wickham started taking photographs with the plastic Kodak Colourburst) and also that since 1983 he is as much a printmaker as photographer, Wickham’s Mount Buffalo project should be seen as:

“self-conscious and ironic: his intention was to examine shadows underlying our culture’s conceptions of wildness and wildness. The choice of alpine landscapes, covered in snow or mist, was not intended to show another side of Australia. Nor did he mean to invent another new landscape aesthetic as a way beyond the bind that he, like many younger artists felt in the mid-1970s, when it was clear that modernist art had finally run its course.”

While acknowledging that a “problem here is that [his] works look considerably like latter-day modernist landscapes, participating in the transcendentalism of that photography,” there are several aspects of Wickham’s works noted by Green that can be seen as aligning with the postmodern impulse, including his self-consciousness in staging what he acknowledges is an artificially persevered ‘wilderness, selecting the point of view and using devices of classical landscape to create a formal construction to appropriate and mimic viewpoints, subjects, and techniques of earlier periods of art, such as nineteenth-century landscape photography to counterfeit the aesthetics of the past; an absence of the human, or the Rückenfigur as observer or mediator, challenges traditional notions of representation and shifts the discourse to the natural environment; and by working outside the American West Coast fine-print tradition in photography, Wickham located himself within the orbit of contemporary theory.

In ‘Nostalgic journey through the landscape’, his review of Wickham’s show at Stephen McLaughlan Gallery, Melbourne, Robert Nelson, writing in The Age on 16 June 2001, seizes on the title of the show “from Stefan Weisz for Elizabeth, Emil, Georg Weisz and Margaret Lasica” as referring to Central European refugees who came to Melbourne in the late 1930s, bringing with them an appreciaton of music, literature, and art, and delighting in a familiar landscape around Mount Buffalo Chalet, the first ski resort in the Victorian Alps.

In fact, more than being a “salutation of a pathetic old central European postcard,” the show’s title is more personal. Margaret Lasica, born Margaret Weiss in Vienna, migrated to Australia in 1939 where her family took the Anglo surname Wickham on arrival in Australia. She later married commercial lawyer William Lasica, first Chairperson of the Centre for Contemporary Photography. Margaret was a student of Ruth Bergner and performed in the Modern Ballet Group in Melbourne in the 1950s as an early pioneer of modern dance in Australia.

Knowing that enhances the poignancy that Nelson emphasises in the way Wickham’s photographs deviate from the traditional depiction of the Australian landscape, eschewing vibrant colours and, while using colour film, depicts in monochrome resemblance to remembered European scenery, and the longing, mystery, and sublime beauty of German romantic iconography, which for the reviewer introduces a sense of nostalgia and a deeper emotional connection to the landscape.

A more sombre note still, and an ecological one, is that close inspection reveals the aftermath of a bushfire; charred branches and the botanical injury caused by the fire, a perception that challenges the idealised notion of untouched and pristine landscapes of traditional landscape photography.

This realisation remains consistent throughout Wickham’s oeuvre.

While national holdings such as those in the Australian National Gallery are of Stephen Wickham’s painting and printmaking, his photography is in the Museum of Australian Photography, State of Library of Victoria, Deakin University, RACV Collection, Murray Art Museum Albury (MAMA), Counihan Gallery, La Trobe Regional Gallery, Arts Centre Gold Coast, Australian Embassy Washington DC, Ballarat Fine Art Gallery, State of Library of Victoria, National Library of Australia.

6 thoughts on “The Alumni: Stephen Wickham”