Paul Lambeth is a quietly spoken, modest man. I see him as a ‘quiet achiever’. In April 2024, I sat down to chat about his life in photography. He told me such interesting stories about his life, and then over the next month or so wrote many pieces to flesh out his story.

Merle Hathaway, 26 May 2024

Paul Lambeth may be the youngest person to graduate from the Prahran CAE, commencing his first year there in 1975 at the age of 17.

His long and meandering career includes commercial and creative photography, festival management and teaching photography in metropolitan and regional Australia.

Paul’s path to Prahran came via John Twegg, a teacher in training at Swinburne Community School. In 1972 and 1973 Paul was a student at this newly formed ‘experimental’ school. John was a recent Prahran photography graduate.

“John had the Prahran passion. I recall his love for German cameras and his considered way of viewing the world. I guess John was the first to introduce me to think about photography as an art form. Subsequently, I applied to do the Preliminary Year (an art year 12) at Prahran, with intent to continue photography studies at Prahran”.

The Community School offered many experiences for Paul, including spending time with ABC Radio AM Program journalists. The concept of work experience hadn’t yet entered mainstream secondary school education in Australia.

“I recall going with an ABC journalist to a Toorak apartment to interview Bobby Limb, a bit of a Radio and TV legend at the time. Bobby was very hospitable, offering the Journo and myself a glass of whisky. It wasn’t yet 10 in the morning; I was 14 years old. A polite ‘no thank you’ from me was accepted, drinks were poured and the interview proceeded.

Swinburne Community School, for such a small school, made a considerable contribution to the cultural, sporting and academic life of Australia. A few names of fellow students come to mind, including Hawthorn footballer Robert DiPierdomenico, Comedian, Actor and Writer Gina Riley, Photographer Peter Milne and Musician Rowland S Howard.”

Paul’s life events included drifting down the Murray River on a home-made raft, time on a fishing boat off the North West Coast of Western Australia, his time on a small island in Greece and following the path of Australian explorers Burke and Wills. I suggested he was something of an adventurer, but he disagreed.

“Yes, at times I have left the comfort and predictability of middle class Australian suburban life, however when I have followed an idea outside of my urban usual, I’ve met people who are not adventuring, they are just living their lives. The events we have discussed all have background details, which contextualise why and how I came to do the things I have done”.

Sitting in Paul’s studio in an outer suburb of Ballarat, our conversation wandered into the context of the why and how some of these experiences came to be.

“Like us all, I’m very much a product of my time and place. I was in my mid-teens during the Whitlam years. There was something optimistic, creatively contagious, and at times naïve at this time in Australia. For example, in 1973 at 15 years old, without any knowledge of how to do it, I applied for a grant to make a film. I was in fifth form (year 11) at Swinburne Community School. The film was to document the journey of a small group of boys floating down the Murray River from Cobram to Echuca on two home-made rafts. I was one of those boys. The film funding body at the time showed interest; I received written and verbal support for my idea. For a number of reasons, my lack of skills being key, the film was never made. The interest to fund the film came too late. The raft trip proceeded. On the first day I lost my pack overboard and spent the next two weeks with a borrowed mosquito net and the clothes I stood in. I don’t recall being particularly bothered by my lack of possessions. Optimistic times indeed. We all survived.”

In 1975 Paul commenced studying at Prahran College of Advanced Education, describing the experience as ‘Free Range’ and somewhat raucous.

“The Prahran photo department education style didn’t suit all students, some fell away. Having come from a Community School secondary education, the style suited me. There were subject names, timetables etc but I doubt there was a curriculum in the formal education sense. I don’t state the potential lack of curriculum as a negative. The structure from my perspective largely hinged on the characters of staff.

In 1975, I had little idea about the world and no idea what an art school was. This wasn’t a problem, I don’t think the staff knew what an art school was either. And this perhaps, was their great strength. They were not acting out art school educator stereotypes. There was no attempt to perpetuate the Salon or Royal Academy art school models of France and England. Other ideas were present, acted out and for the most part accepted. Athol’s very Melbourne suit with extended cigarette holder, Paul Cox’s lived in black corduroy suit, Derek Lee’s London polo tops, Brian Gracey’s leather jacket. John Cato didn’t need to follow a dress code; he was a photography icon without props. I don’t make these observations as criticism, we as students had our own dress codes, reflecting the times.

Teaching photography as an Art form was a relatively new concept in Australia. I experienced all staff as generous. John Cato always made time to assist me with that elusive target, a high quality black and white print. Paul Cox was always up for philosophical discussion, at the College or at his home. Athol gave me his old wood contact print frames, suitable for my 5×7 Linhof Technika Camera. Prahran photo department in the 1970s, was a moment in time”.

Paul, like many other Prahran graduates, recalls much of the learning in the Photography Department came from fellow students. While describing the place as “raucous”, Paul emphasised the relationship with fellow students was certainly central to the educational experience, with the following qualification.

“Some of my fellow students have placed much weight on the student to student learning at Prahran, with some criticism of staff contribution. My view is, the environment for investigation of concepts and technical functionality was created and nurtured by staff. An environment that supported independent learning, to me, was a positive educational experience”.

Prahran 3rd Year Photography Students, 1976

The photos above document a student-led initiative; a mini-revolution on campus. Students thought there should be more structure or perhaps greater clarity in the course intent. Paul says, “It wasn’t really attacking the staff; it was theatre”, and recalls that while Athol Shmith was noticeably hurt by the student action, he made changes to the programme and brought Peter Turner from England to work with the department. Turner was a notable photographer, curator, and writer and long-term editor of ‘Creative Camera’. 1

While at Prahran, Paul commenced working for Boney Leder Photo Studios, operated by two Jewish men in suburban Melbourne. He received excellent support from this small business.

“They were well known in Melbourne’s Jewish community, which is where most of their work came from. They were wonderfully generous to me, given my limited skills and capacity to add much to their business. I had no knowledge of their personal histories, however, as a 17 year old, I experienced their humility and generosity first hand. I was grateful at the time, and continue to be so.

Working for the studio presented me with a problem, I didn’t drive. Working at the studio was no problem, as it was a short tram ride from home. However, as trust built, I was asked to cover jobs in various locations around Melbourne, many of these jobs were for The Australian Jewish News. I wasn’t old enough to sit a drivers licence test. My Mother kindly drove me to a couple of jobs, waiting outside while I completed the shoot, feigning the role of professional photographer. I bought a small motorcycle, enabling me to strap the camera bag and tripod on the rear rack and complete jobs a distance from home, now I was professional. I was inducted into many parts of the Jewish community, religious, philanthropic, community and family events, a camera around my neck my badge of authenticity.”

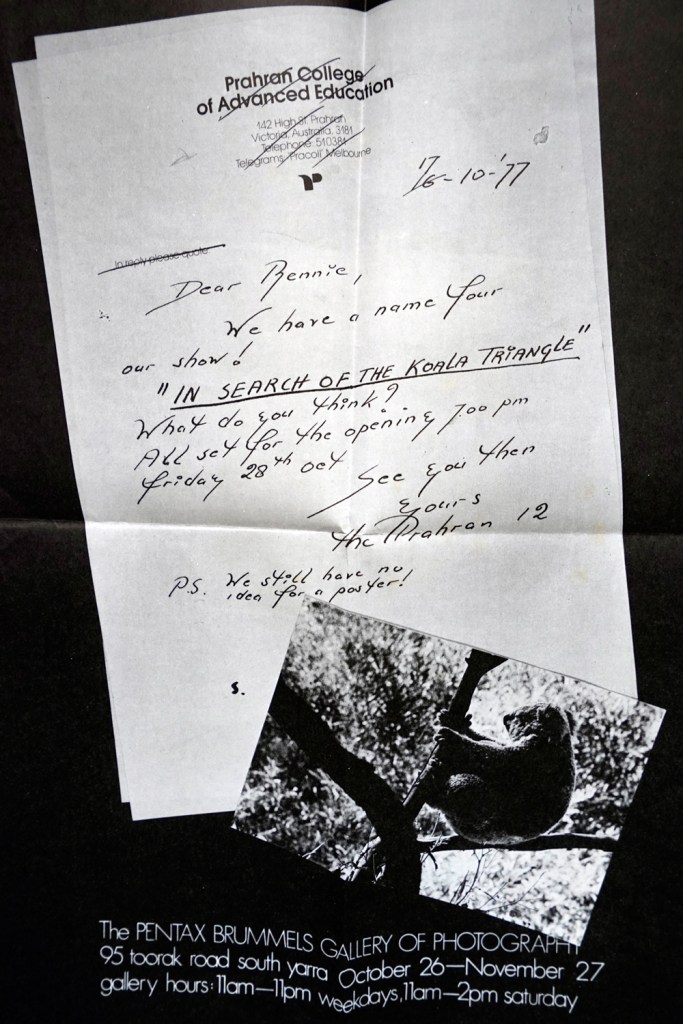

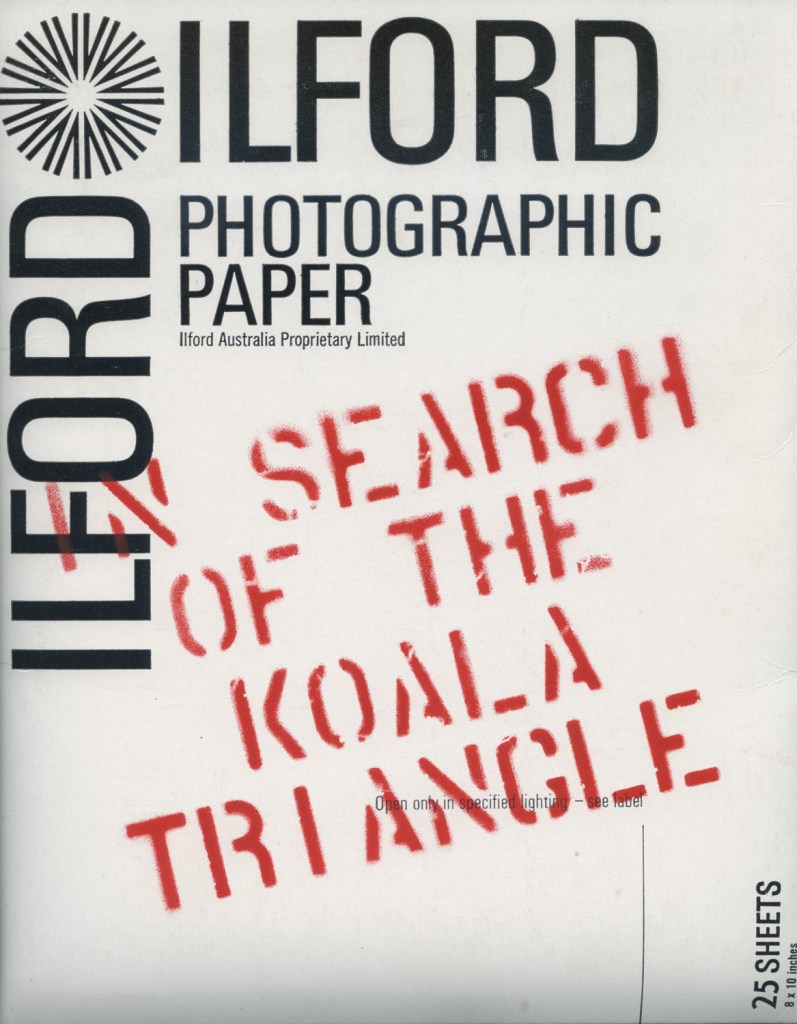

In 1977 the students held an exhibition, ‘In Search of the Koala Triangle’ at The Pentax Brummels Gallery of Photography. 2 In the 1970s, under the directorship of Rennie Ellis, it was the first in Australia to specialise in photography.

Post Prahran, Paul worked in a cine film laboratory with the notional job title of Photographic Chemist. “The only reason I worked there was to save enough money to go to Europe”, he said.

I asked Paul how he came to spend a year or more on a tiny Greek island.

“Sometime in 1979, I had conversations with Paul Cox about Astypalea, a small island in the Dodecanese, Greece. Paul had bought a house and made an 8mm movie on the island. My imagination and curiosity had been sparked. With a one-way ticket to Greece, I left my Melbourne life and spent much of 1979/1980 on Astypalea, living in Paul’s house. I augmented my savings by painting a few murals. I didn’t earn cash from this, but was paid in meals. Some years later Paul made a feature length film titled ‘Island’ on Astypalea. In the late 1980s, seeing the film in Melbourne, I recognised actual and characterised people in the film. I returned to Astypalea in 2010, more than thirty years after my time there. I was in Athens to deliver a paper at an International Art Conference, titled ‘Research, Scholarly Art Practice’. Following the conference, I travelled to the island. A few Astypalean locals arranged a house for my temporary stay. The world, Astypalea, and I had changed. It was good to return, but very little from the long ago original experience could be repeated. I still have contact with some people associated with Astypalea”.

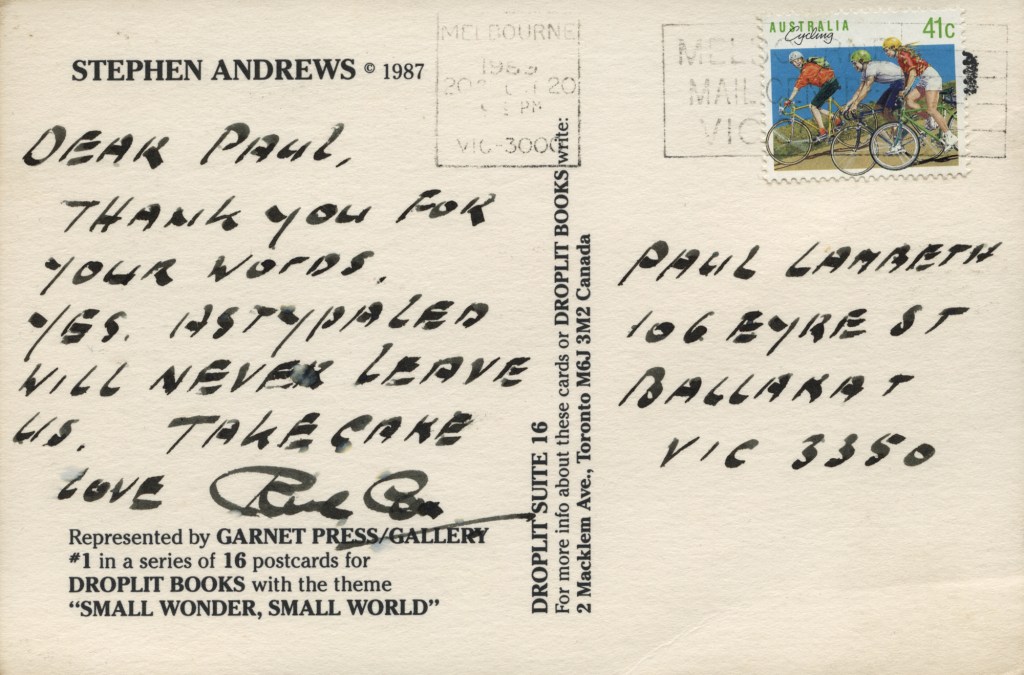

Paul Cox and Paul Lambeth communicated sporadically over the years, and the tutor was a strong mentor and supporter for Paul and his work.

“When I left Greece, I spent some time in London and Paris. In London I stayed in Australian artist Dan Mafe’s studio in Wapping, East London. The studio was in an old Warehouse overlooking the Thames. A fantastic location, however the living conditions were very basic. Dan’s studio did not have windows, artificial light only. The bathroom was a shared cold water tap with basin in the hallway.

In 1980 East London was yet to be gentrified. It was strange for me, a boy from the inner Eastern Suburbs of faraway Melbourne, seeing the devastation from WWII still evident. Nearby East India docks had many vacant areas of land that were piles of rubble. I assumed these were the legacy of the London Blitz. A month or so earlier while on Astypalea, in an abandoned house, I found a German soldier’s gunny sack with a printed swastika. Walking in the hills behind the village I came upon a German soldiers helmet. The helmet had a bullet hole, front and centre. I imagined a shepherd had used the helmet as target practice, while venting feelings. Race riots were happening in London at this time, precursors to the infamous Brixton riots. While I was there, a train on the underground was tipped over by an angry mob. Punk Rock had made its presence felt, anger the central expression. Sid Vicious from the ‘Sex Pistols’ had recently passed. ‘The Clash’ had also left their mark. It was an edgy place in an edgy time. This was during the Thatcher years. Wapping became a battle ground between Thatcherism and the trade unions. Rupert Murdoch was operating in the background, wanting to move his printing plant to Wapping. The national miners’ strike followed a few years later, another clash between Unions and the Thatcher Government. History would suggest Thatcherism won. I meandered around this environment innocently and without harm, though some incidents stay in memory.

My appetite for photography during this time was still with me. Without a darkroom I turned to making Polaroid images.”

After his return to Melbourne, his professional photography career took off in unpredicted ways.

“Back in Melbourne, I commenced work as an assistant photographer with the Commonwealth Department of Housing and Construction. I had no money; this was the first opportunity that presented. It was a great job, photographically documenting various government building projects in Melbourne. I was the junior in the department, but I was provided with opportunity to build my photography skills. I was only in this job for a relatively short time, the Federal Government were going through a process of centralising activity to Canberra. I was loving life back in Melbourne and chose to change jobs rather than relocate to Canberra.

Technically speaking, I ought not to have been the successful applicant for my next job as a Medical Photographer with the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital. I was an Art School Graduate, untrained in the technical specifics required for this work. Despite my self-doubt, I approached this job with enthusiasm and received much support from the Head Photographer.

There were a few stand out experiences during my time at the Eye and Ear. Three photographers and an illustrator were employed, operating from studios in a terrace house opposite the hospital. Hierarchically speaking, I was in the middle, a senior photographer above and a junior below. On reflection, in consideration of my young age, I held a reasonable level of responsibility. The work was varied: studio portraits, retinal angiography, documentation for research, education and at times for medico legal purposes. I photographed the progress of the new hospital building on the corner of Victoria and Gisbourne Streets East Melbourne. I established a position on the roof of St Vincents Private Hospital opposite, with photographs shot on a Monthly basis. I used the same 5”x 4” Linhof camera and tripod for all images, (a similar version of my camera used at Prahran) marking the tripod leg position on the concrete roof with nail polish.

During this time, I produced work for a number of eminent people in the medical field including Prof Graeme Clarke, documenting the development of the bionic ear, later to be known as the Cochlear Ear Implant. It was also at this time I worked for Sir Edward (Weary) Dunlop. Sir Edward would come to the studio with requests for photography jobs, referring to me as ‘Paul with the good eyes’. I can only assume this was because of my youth, I was able to focus well. On one occasion I went with him to the University of Melbourne; I believe it was the pathology department. The rooms had long stainless steel tables. At Sir Edwards request, an attendant brought a lidded bucket and placed it on the table. Sir Edward, in protective clothing lifted a human head from the bucket and proceeded to remove an eye. On his direction, I photographically documented the process.

While working as a Medical Photographer, I also pursued my own vision. In 1976 Athol Shmith introduced a French photographer to our group, Jean-Marc LePechoux. Jean-Marc was the editor of ‘Light Vision, Australia’s International Photography Magazine’, first published in 1977. In 1983, Jean-Marc in collaboration with Peter Beilby published ‘The Australian Photography Year Book’. Images from my personal practice were included. I don’t know the background to all photographers represented in these publications, but a number were Prahran graduates.“

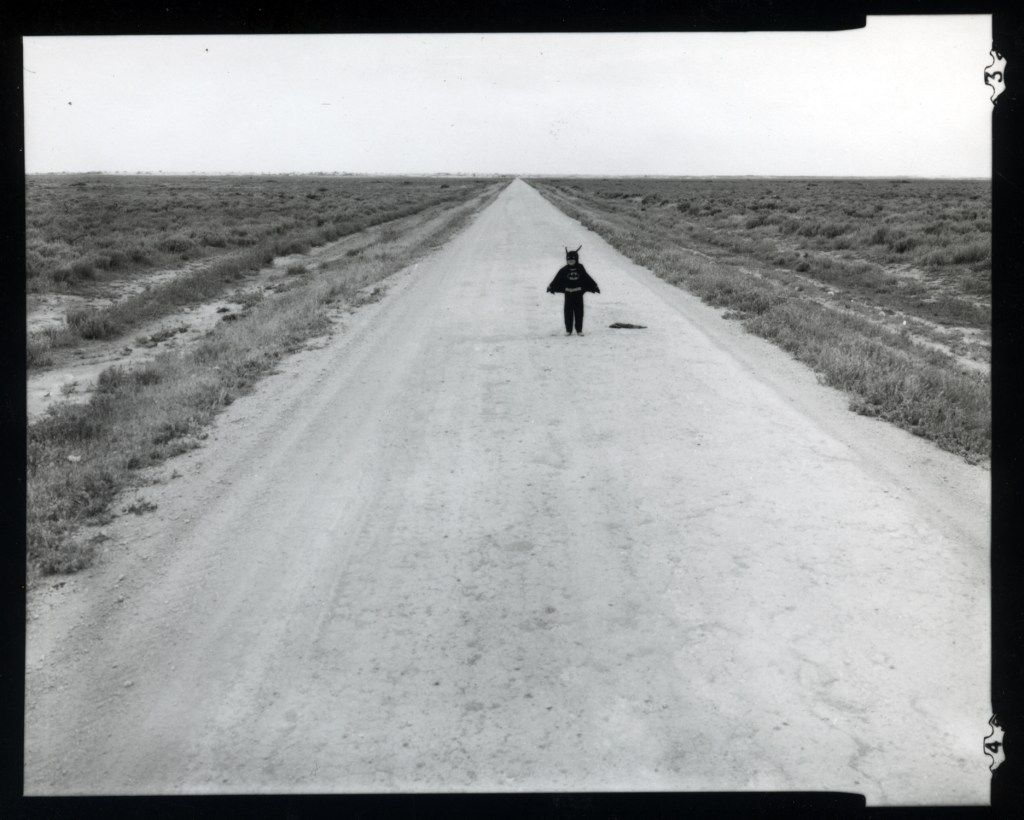

During this time Paul embarked on a project in response to his own sense of love and loss. His son became the subject over the next 14 years, c 1986 -2000.

Alister Heighway: Shooting ‘Batman at Mungo’ 2 & 1, 1989 .

Following my time at the Eye and Ear Hospital, I took a similar job with The Austin Hospital and University of Melbourne. While the work was interesting and for the most part challenging, I was aware of the specialisation of the work. I became a professional member of a small group, The Australian Institute of Medical and Biological Illustrators. I was aware of the small scale, and therefore the limited employment opportunities this field had to offer in Australia. I did this job for two years before opting to return to study.

In 1984, higher degrees were not available in studio arts practice in Australia. The closest I could get in Melbourne was a Post Graduate Diploma in Visual and Performing Arts and a Diploma of Education. My intent was to broaden my employment options. I enrolled in both programs at the same time, completing both qualifications in two years. While I met some inspiring people, I don’t think of these educational experiences as impactful.”

I asked Paul if this further study had led him to pursue a career in education.

“Not initially, during my return to study, I made a basic living illustrating, primarily for the Victorian Teachers Union and University of Melbourne student magazine, Farrago. I also worked part time as a Music Teacher. My first, and only substantial teaching job didn’t commence until 1987 in the Art School of SMB, The School of Mines and Industries Ballarat. SMB was considered to be the oldest continuous running Art School in Australia. I have no doubt I generated my teaching style with influence from my own photographic education at Prahran.

My career has at times, enabled me to have overlapping multiple roles with the title ‘photographer’. In the mid 1980s, I had left the world of medical photography and was renovating my cottage in Daylesford when two suited detectives knocked on my front door. The only people coming to the front door were strangers, everyone I knew came to the back door. I was handed a subpoena to attend court as a witness in a murder case. That is, my photographs were being used as evidence in the prosecution. I needed to attend court to confirm the authenticity of the photographs and the context in which they were made. The case was high profile at the time, attracting some media attention. A woman was charged with murdering her husband by poisoning over time, the prosecution stating he received his final dose in hospital. I had photographed the symptoms of his poisoning, without knowing what his medical situation was. My job as a photographer was to clearly illustrate the darkening lines around his fingernails, apparently a visual manifestation of heavy metal arsenic poisoning. This was an example of photographs being used in a medico – legal context.”

You have also had quite a long career as a teacher of photography.

“There were many highlights. Around the mid 1990s, we commenced a pilot program in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Art and Design. I taught photography in this program. Working with the local Aboriginal Co-op and the Koori Liaison Unit, the program grew into a Certificate IV in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Art and Design, a very successful and long running program within the Ballarat community. Eventually, the program was paused.

Some years later, as Head of Department at the Arts Academy University of Ballarat, working with the Ballarat and District Aboriginal Co-op, we re-launched a Visual Arts program for Indigenous students. The program was again successful. It led to a number of Indigenous Art groups operating from this region, including ‘Maru Mara’ and the ‘Pitcha Makin Fellas’, the latter eventually working from the Indigenous Visual Arts studio established within The Arts Academy. Many of the artists from these groups were graduates of the earlier programs. Working with Ballarat artist, Peter Widmer, the Pitcha Makin Fellas have continued on their creative path. 3

In 2009 I was nominated for a ‘Wurreker Award’, an initiative of the Victorian Aboriginal Education Association. These experiences were helpful many years later, working with Indigenous groups, Latji Latji, Barkindji, Mutthi Mutthi, and Ngiyampaa, in North Western Victoria and South Western New South Wales.

So, were you able to continue with your own work at this time?

“I continued to make and exhibit images, though not purely photographic. In the late 1980s, with support from the Head of Department at SMB, we attracted a major grant to establish a Mac Studio/Lab in Ballarat, the first of its kind in this region.

I completed a two or three day course at Boxhill TAFE, making me the expert, apparently. For a long time I had a love hate relationship with making images digitally. The technology wasn’t there yet. I stuck with it and eventually came to some arrangement in my mind about the process. It was closer to making images with Polaroid than it was to the Optical/Mechanical/Chemical process that is analogue photography. The immediacy of the digital process I loved. I exhibited photography (analogue and digital) and paintings during this time, primarily in regional galleries, including Ballarat, Horsham, Ararat and Mildura.”

Exhibited at Katsui Gallery, Ballarat

“In the early 2000s, I received a funded Fellowship to review the impact of digital technology on tertiary art and design education in New Zealand and Australia. The outcome for me, in completing this Fellowship, was the introduction and process of Research.”

For his Master of Arts Research, sometime after this, Paul pursued another project, this time using painting and poetry rather than photography.

“If there is a central theme in work I have produced over a number of decades, it is an exploration of human folly and courage. I was drawn to the Burke and Wills story as an extraordinary example of these seemingly opposite human attributes.

My MA research was a practice led project titled ‘If I Belong Here, How Did That Come To Be…?’ I used the Burke and Wills crossing of the Australian continent in 1860 – 1861 to creatively explore the issues behind such a fateful, albeit intrepid undertaking, from a contemporary perspective. A consistent theme in my art work has been the relationship we have with our environment. An important component of this research was to follow in the footsteps of the explorers, not literally by foot, but using the tools of our times, in this case a Subaru Forester, a swag and for the most parts of the journey, a road. Since the late 1980s I had been visiting far Western NSW out of interest, particularly the Wilandra Lakes District. This area has great significance in the history of human habitation, notably Lake Mungo. The practice part of the project led me to use painting and poetry in the presentation of my findings.

In 2008, I found myself sitting on the banks of Cooper Creek near the Dig Tree, in Far Western Queensland. This was the site of Robert O’Hara Burke and William John Wills death. It was here, in the imagined voices of the Colonial explorers I wrote the vers libre poem ‘Robert O’Hara Burke and William John Wills.“

“Following my MA research I presented at a Burke and Wills symposium, the 150th Anniversary of the expedition. I read my poem and projected images of my paintings and those of other artists, in particular paintings by Ludwig Becker, the expeditions artist. Subsequently my paintings and poem was published by CSIRO in ‘The Aboriginal Story of Burke and Wills, Forgotten Narratives’”. 4

“Around this time, 2009, I commenced an Early Career Researcher Program with the University of Ballarat. During and on completion of the program, I participated in numerous conferences around Australia and in Greece. My key question was to understand and communicate the role of research within the creative arts in a University context. I understood good research can be defined as funded research. Models of research have evolved in disciplines outside of arts practice and are based on determining a problem to be solved, laying out a model to solve the problem and documenting the outcomes. I had never considered the Arts to have a problem requiring a traditional research approach, aside from some quantitative research to measure or increase ‘bums on seats’ engagement. An Arts practice usually reflects individual and/or collective issues, problematic or not. The title of some work undertaken during this period was, ‘Research, Scholarly Art Practice’. The Career Research Program led to the commencement of a PhD”.

Paul’s next role was as Director at Arts Mildura.

“With impending funding cuts, I went looking for new opportunity. I departed the University of Ballarat in 2012. Retrospectively I can say, this was the correct decision for me. Art Schools as I experienced them had dramatically changed. I took the job Director Arts Mildura in the same year. Mildura was an area I had been visiting for more than 20 years. I had exhibited in Palimpsest #3 in Mildura in 2000 and also at the Mildura Art Centre, ‘Vistas & Observations, Mungo, Arumpo & Zanci’ in 2000/2001. At this time, Arts Mildura was a small arts organisation with a big appetite. Mildura is an isolated community, providing participation in cultural activity for people across a wide region, including The Murray River International Music Festival, The Mildura Wentworth Arts Festival, The Mildura Writers Festival, Palimpsest (Bienniale) and The Mildura Jazz Food and Wine Festival, in addition to Wallflower Photography Gallery (Curatorial work by Kristian Haggblom) My time in Mildura was a rich and exhilarating period in my career. Photography playing an important part in my promotion and documentation of the organisations activity. Eminent poet Les Murray summarised me in a three word poem handwritten in his book of poems, ‘Learning Human’, Les wrote, ‘for Paul; click’.”

Paul Lambeth (L): Thomas Keneally 02 Mildura, 2015 (R) Bruce Pascoe 01 Mildura 2014

In Mildura Paul Lambeth exhibited ‘Taken to another place’ at the Art Vault, Mildura, 2015. 5 In opening the exhibition Professor Paul Kane from Vassar College, New York, said:

Paul’s work exemplifies perfectly the remark by Marcel Proust, that “The only real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.” That is what we are given here: new eyes with which to see… In these photographs we are, indeed, “taken to another place” within a place we already know, or thought we knew. To travel by car in this landscape is to be carried along in a narrative of our own creation, as each scene emerges and recedes like a chapter in a novel. Paul’s photographs make us aware of this unconscious or subconscious process. On the road, we are driven to an apprehension of the land that is highly personal and therefore highly imaginative. Only the imagination can deal with the speed at which we move, as the discursive mind is overwhelmed by the constant stream of unprocessed visual impressions.

Leaving Mildura, Paul had a break in Europe before returning to Ballarat.

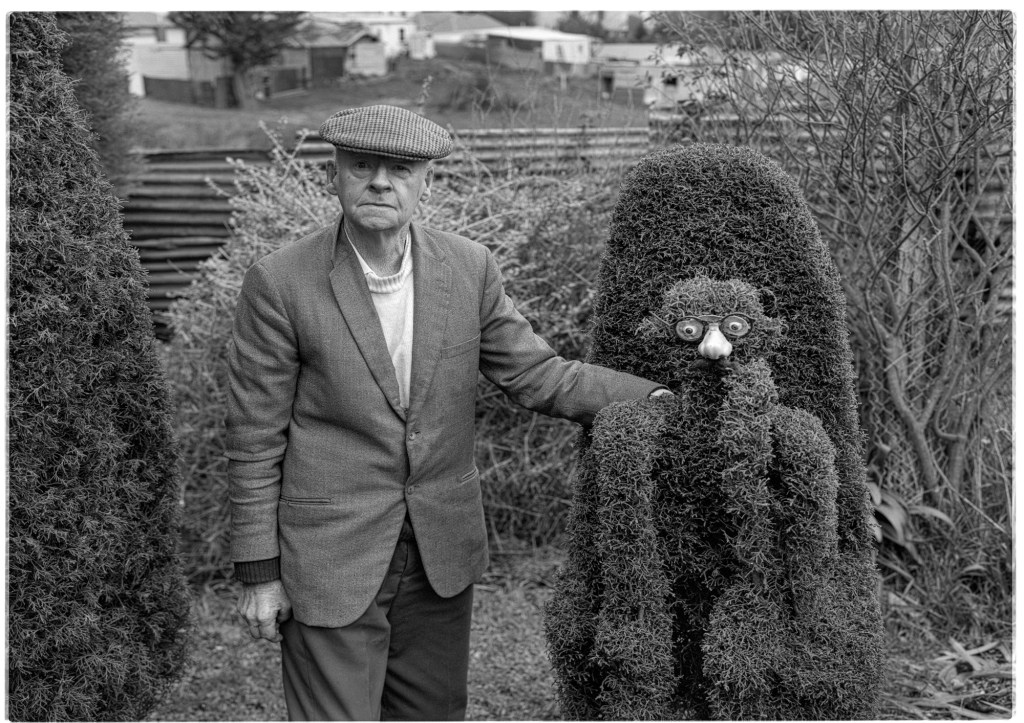

“ I came back to Ballarat and continued my photography practice, both commercial and self-set. Some activity I have been involved with sits between art practice, education and commercial activity, notably the workshops and residencies I have done in Nathalia at The Grain Store. There is a connection between this activity and Prahran in the 1970s. Humanist artist William Kelly (Bill), former Head VCA established The Grain Store, an Arts Org in Nathalia, with his wife Veronica. Bill (dec) and Veronica were friends of Paul Cox, John Cato and Athol Shmith. Bill and Veronica make cameo appearances in Paul Cox’s films. Out of choice, the times I have stayed in Nathalia, I have camped on a local’s property. I camp in my little house on the back of my ute. Bill Kelly suggested I was ‘doing a John Cato’. John had a camper trailer he carted around the country, allowing him to spend time in the environment where his photographs were created. Perhaps John Cato influenced me in more ways than as a photographer.”

Since graduating from Prahran, photography directly and indirectly, has been a key component of his arts practice and a way to making a living. At times these boundaries are blurred. Paul is still an active commercial photographer.

For the 2023 Ballarat International Foto Biennale, Ballarat’s Eureka Centre showed Paul Lambeth’s ‘All my lifetime it was there. . . ’ The black and white photographs from Ballarat East dated from a 1992 National Trust of Victoria funded heritage project. They highlight substantial changes in one of Australia’s most significant colonial era urban areas. 6

During BIFB, Paul and his sister, Lyn Lambeth, exhibited ‘fLIGHT’ at the Old Butcher’s Shop Gallery, Soldiers Hill. Lyn’s delicate 3-D found object bird sculptures were complemented by Paul’s detailed photographs of the organic world, which hark back to some of his early experimental photography at Prahran CAE.

I’ll give Paul the last words:

“…I like to think of myself as a bush walker who makes images. However, it would be more accurate to say I am a bush stroller, or bush sitter who makes images. The process of photography can be a very fast method of making images, a fraction of a second in fact, a fabulous power of the medium, also a limitation. By sitting quietly for hours, or at times days, I slow the process of seeing. Rummaging around in the primordial detail gives me a sense of being close to life. However, as in life, my process can be contradictory. At times images are easy to find, at others very illusive. If nothing else, I think of my images as facsimiles of experience, my experience.”

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Turner_(writer_and_photographer) ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brummels_Gallery ↩︎

- https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/melbourne-now/artists/pitcha-makin-fellas/ ↩︎

- https://www.publish.csiro.au/book/6993/ ↩︎

- https://www.paullambeth.com/taken-to-another-place-2014—2015.html ↩︎

- https://www.eurekacentreballarat.com.au/all-my-lifetime-it-was-there-paul-lambeth ↩︎

I’d like to thank Paul for his cooperation on this project – he spent considerable time sending me new images and texts to flesh out the story.

Merle Hathaway 25 May 2024

LikeLiked by 1 person

An inspirational and moving story well told. Thank you Merle. Thank you Paul.

LikeLiked by 1 person