Fine art is considered to represent an artist’s personal vision and creative expression. Abstraction in photography is argued to transform photography from mere documentation to an art form that expresses unique personal and complex ideas, subtle emotions, and new concepts. John Cato’s was such a practice.

We past students of Prahran College of Advanced Education met him as our lecturer. We learned that John was a pedigreed photographer. He made his living from the medium and thought hard about it. Through his father John met practitioners of the highest ranks in the medium, from the moment he was born. He was the son of Jack Cato, an accomplished Pictorialist and giant in the Australian professional photography industry whose last years and much of his savings were spent writing The Story of the Camera in Australia, the country’s first history of the medium.

John was apprenticed in his father’s studio from the age of 12, leaving only to join the Navy for World War II. It is an episode he related to me from his war years that sticks in my mind to give some insight into what he believed and felt. He was on a wharf in New Guinea while Japanese prisoners-of-war were being offloaded from a ship. A digger emerged from the huts at the end of the wharf, walked up to one of the Japanese, unhooked his rifle from his shoulder and shot the man dead, saying “This is for my mates.”.

Cato in telling his war story 30 years after it had ended, to someone with no memory or experience of the war and whose own father had remained completely silent about it, was expecting his story to be a shock. It was, but not in the way he expected. In my experience, everyone of Cato’s generation hated the ‘Japs’, believing nothing good about them; they represented everything that the war was, and they were evil. Not Cato. Clearly he felt the digger’s act was cowardly, an ugly war crime that let his country down, that had horrified him. Cato witnessed the event as a young man, younger than many of the students he taught. The soldier’s deed was immoral, it was evil, and John felt it still. Here was a man who was not afraid of standing against public opinion, who stood by his own beliefs and morals. And so did he teach.

His method was to seek out the aptitudes and endowments of each student who came before him; his teaching and mentorship involved a deep empathy with each student’s approach. He was compassionate, almost clairvoyant in being able to very quickly identify one’s strengths and it was on those he would concentrate, unafraid to express criticism; but only in terms of how a certain fault might detract from a certain strength.

At he same time, he taught by example, through his own practice. Released from professional photography and inspired by his teaching, and during breaks from teaching, he undertook the making of vast series of images that might span years. Landscapes in a Figure, his first photographic essay was begun four years before he left his commercial practice.

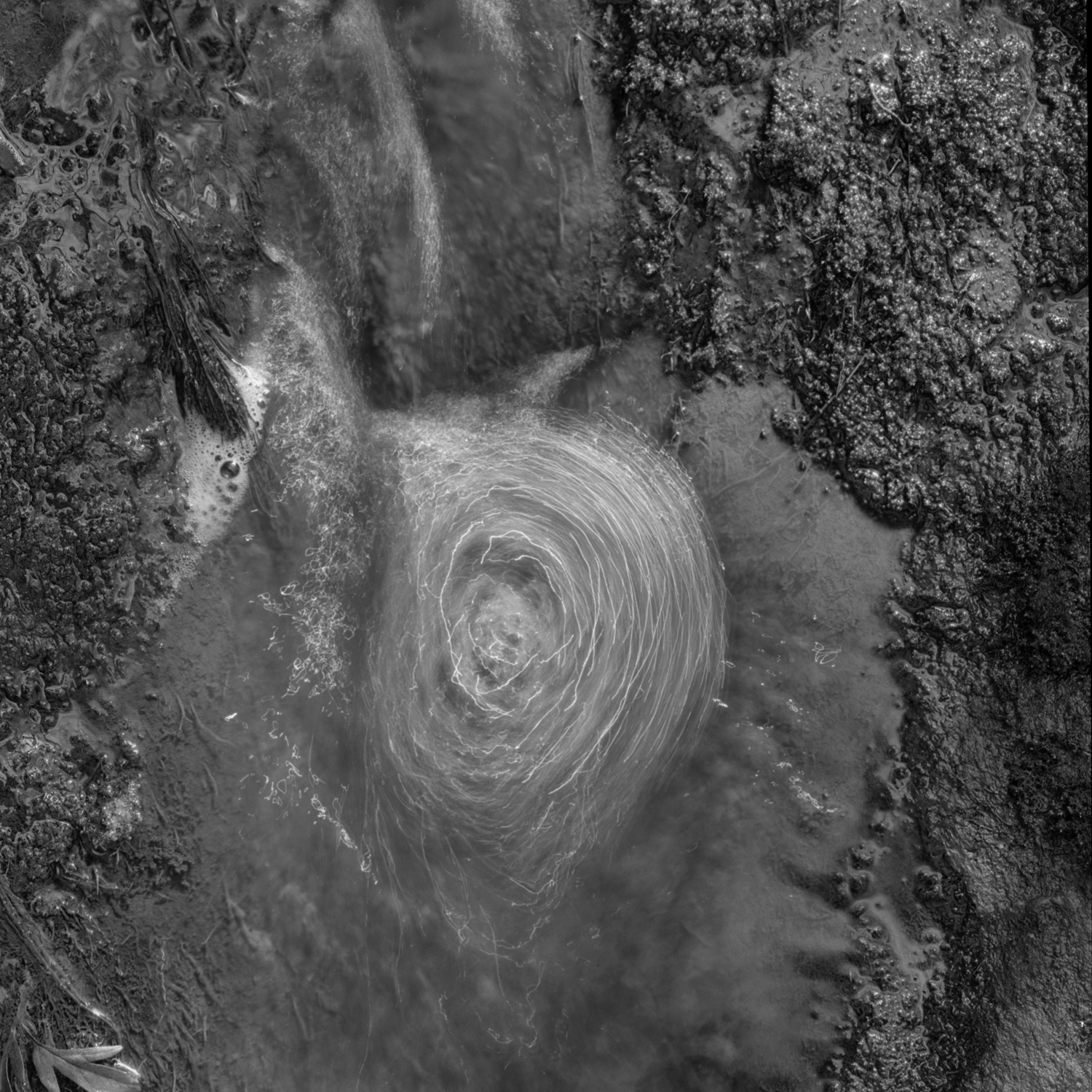

He completed the essay in five black and white photo sequences between 1971 and 1979. It was part of his colour series Earth Song, the early part of which was exhibited in a group show at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1971, at a time when it was still struggling to be recognised as an art form in Australia, and prior to Jennie Boddington taking up, in 1972, the first curatorship of photography in a public gallery in Australia.

It is difficult now to imagine, from its faded remains, the positive prints from Ektachrome transparencies in the NGV collection that one can find online, how radical was Cato’s Earth Song of 1969. Part of a group exhibition Frontiers at the National Gallery of Victoria, October, 1971 beside experimental work by Peter Medlin, Joseph Stanislaus Ostoja-Kotkowski, Mark Strizic and John Wilkins, Cato’s series, the first public excursion of work produced while still a commercial photographer, was displayed on red panels and illuminated by timed strobe lights.  Captions were Cato’s original poetic texts, such as “To plant a liquid tree / and consummate / creation”, or “while deep in clay corrupt / aborted, / vain promise lies / and dies unborn, / homo sapientior,” which impress upon the reader the self-education undertaken by its author whose formal schooling ceased at Grade Six.

Captions were Cato’s original poetic texts, such as “To plant a liquid tree / and consummate / creation”, or “while deep in clay corrupt / aborted, / vain promise lies / and dies unborn, / homo sapientior,” which impress upon the reader the self-education undertaken by its author whose formal schooling ceased at Grade Six.

The scale of his projects match their vision. A virtuoso printer himself, Cato was able to carve images from the Australian outback landscape into powerful signs, like the petroglyphs of ancient First Peoples. His black and white prints exploit the full range of tones, exaggerating contrast or flattening it, whatever is needed to draw out the symbolic.

A self-proclaimed animist, he felt, heard and saw the spirits of the landscape as he spent days alone, photographing along the Coorong where the sea, the big Murray River and dunes meet; or up in the stark fossilised ranges of South Australia. Thus his images are peopled with beings other than humans.

The epic quality was akin to that of Australian writing of the 50s and 60s, of Eleanor Dark, Xavier Herbert, Dal Stivens, Patrick White and the later Gerald Murnane, in whose book The Plains Cato found a kindred consciousness, and shared ideas with art like that of Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker or Fred Williams, and encompassed the scale of composers like Peter Sculthorpe or Ross Edwards. He is certainly the equal of any of these, though without deserved recognition.

Unlike most animists however, he was a dualist, a state he saw reflected in the medium he used, with its negative and positive renditions enabling him to represent the yin and yang in pairs of images combining or inferring both states. His environmentalist and indigenous sympathies generated a series Broken Spears which represents both black and white struggles against each other and against the landscape, ultimately futile in the white man’s case, while Man Tracks makes vivid the degradation that ‘civilisation’ has wrought.

Once, Cato, then dead 5 years, visited me as I kayaked down the Glenelg River with friends. As I watched the shoreline pass me by, its myriad branches, grasses and strata of rock were reflected perfectly in the brimming, still, black water…so perfectly that it became hard to distinguish between reflection and reflected. Rhythmically paddling, with head to the side as I went, I was mesmerised, and recalled vividly John’s exhibition of a series of photographs of reflections of landscape in water, turned on their side. Perhaps the reflections were in this very water (as he traveled frequently through this area taking his photographs). The division of water and land disappeared, and I was seeing the spirits he photographed revealed to me, so very present was the hallucination. Of all of his work, these were the most revelatory to me, so much of the essence of both landscape and photography, the dualist, reflective medium, itself.

The experience of seeing John’s photographs as he saw them, in the landscape, makes me feel he is still out there. If only more Australians could access his work, we would better understand and appreciate this ancient land. As is so typical of this nation, we are slow to recognise our best.

Paul Lambeth, also one of Cato’s students, presents abstraction as a conundrum in these thoughts that he has sent us, with a series he calls Objectless Space.

“In 1975 I travelled on the overnight train to Mildura with my sister and a friend. The old red rattler train departed Melbourne at 7pm and arrived in Mildura at 7am. There were no sleeper carriages on our budget priced ticket. The carriages had passenger booths on one side with a connecting hall the length of the carriage along the other. We shared a booth with some boozy fruit pickers, their suitcases clunking with bottles of alcohol for the journey. At some point in the trip our plan was to darken the booth by half unscrewing the light bulb and pinning a couple of old army blankets across the windows so that we could stretch out on the bench seats and attempt some sleep. Our plan did not align with the fruit pickers understanding of a good trip. After our refusal of their many offers of a drink, they did finally accept we were not going to join them in drinking their way through the journey. They left us to the booth.

“In Mildura, we stayed on a houseboat belonging to a friend which had been written-off in a recent flood and was permanently moored to the river bank amongst the river red gums,. I spent a few days with my camera attempting to make something from these extraordinary trees. More than forty years later, I lived very near this location.

“Back at Prahran, I showed my overexposed high contrast images to John Cato. John asked whether if I was to attempt this subject again “how might I get closer to my intent, what was my intent, would I photograph my girlfriend in this light?” Johns gentle questions were very perceptive and inspirational.

“In 1975 or 1976, we were set a challenge to photographically illustrate a piece of music by the composer Rachmaninoff, an album cover (12 inch vinyl). It may have been Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto Number 2. With John Cato’s words in my head, in the not too distant You Yangs I photographed the shadows of trees as a flattened version of the trees’ presence. During the group assessment process Paul Cox singled out my image as successful. In my view, while confronting, these group assessment processes were positively competitive.

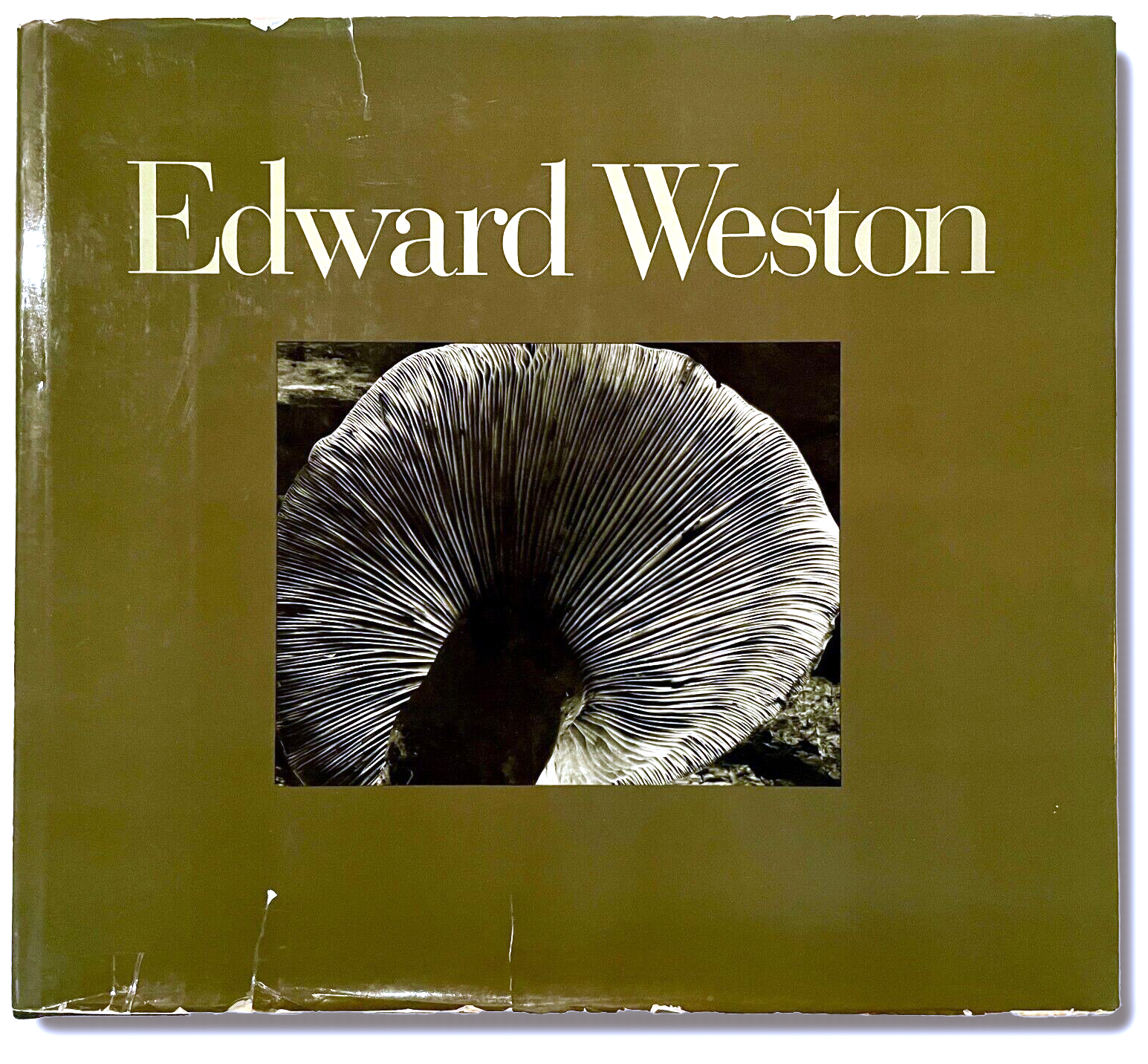

“In 2nd year, 1976 we were set a class assignment ‘Still Life’. I had recently purchased Edward Weston’s book 50 Years in Photography and was deeply moved by his pepper series. I loved the notion of ‘the thing itself, interdependent, interrelated parts of a whole, life itself.’ Following these lines of thought I found a potential origin from the philosophy of Immanuel Kant, ‘the status of objects as they are, independent of representation and observation’. At the time, it seemed to me, Weston had transposed Kant’s concept to the practice of photography.

“I followed this thinking path, using a bean bag as subject matter I abstractly photographed the bag without totally losing the subject matter, to suggest ‘life’. Paul Cox gave me very positive feedback, offering thoughts from Buddhist Philosophy. Paul suggested he had some objects that might be of subject interest to me. I arranged to visit Paul to photograph the objects he had mentioned, a couple of small fragile earth sculptures. Peter Turner and his partner Heather were staying with Paul at the time. I knew nothing of the origins of the sculptures. Heather was curious about my intent, questioning whether I was serious about what I was doing. Retrospectively I can say yes I was serious, but at the time I was uncertain about my direction. It was only a few years later, I was photographing some ancient figurines on the Greek island of Astypalea, brought to me by the local representative of The Greek Archaeological administrative organisation to photographically record. According to local talk, farmers occasionally found valuable artefacts but were reluctant to admit where they were found. While it was illegal to move artefacts, past experience had shown locals that their life could be turned upside down by teams of experts from Athens and beyond if the finds were considered to be historically significant.

“I photographed the artefacts in a Kafaneion, the objects apparently found beside the road.

“In 1977 Ian Lobb presented a formal technique to control exposure and development. The first stage of the Zone System. While John and Paul had spent one on one time with me on controlling density and contrast, it was Ian’s clinical method that enabled me to systematically move forward. John was a master printer, as was Paul. As a young student, watching them print was a mysterious experience. As a parallel experience I use my interest in music as example. I had a strong interest in music and had been learning since I was ten years old. At this time, I could play correct notation, rhythm and tempo of a select piece but could not achieve the same feeling as my teacher. A frustrating reality of inexperience. I merged techniques as offered by Ian Lobb with the metaphysical approaches of Paul and John in my explorations of the semi abstract potential of photography. Athol was also very supportive of my investigations. I had bought a Linhof Technika 5×7 camera. Athol introduced me to a couple of new to me techniques, including contact paper, as opposed to the projection paper I had been using. He also gave me his old contact frames, with photo glass. At the time I didn’t know photo glass existed. Athol’s contact frames were stored in a few tea chests in Paul Cox’s garden shed. With Paul’s support I retrieved them.

“I had read sections of Edward Weston’s Daybooks, though never able to wade through all volumes. I learnt of the concept of ‘equivalents’. I didn’t warm to this concept, despite Ian Lobb using the term in describing one of my photographs. For me, the term represented restriction, an end point, an attempt to nail down the elusive.

“In 1977 Peter Turner [a guest lecturer at Prahran College] set an assignment titled ‘Objectless Space’. The dominant genre of images produced at Prahran during my time was Social Documentary. Photography had carved out an acceptance and separation from other visuals arts practice within this genre. Outside of photography, I had followed other trails, particularly some of the American abstract expressionists. The painters Franz Kline, Lee Krasner, Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock. The latter coming to my attention a few years earlier from the controversy caused by the Australian governments purchase of Blue Poles for 1.3 million dollars. Within photography practice, one of my favourite photographers was Robert Frank, however it was the later work of Aaron Siskind that propelled me forward. Siskind was a fan of the work of Franz Kline. Siskind’s flattened images of graffiti walls and shadows had an intangible but powerful impact on me. I bought a book of Aaron Siskind photographs, still on my shelf. Art History lecturer Norbert Loeffler had highlighted the role of photography in dominating the visual documentary space. Painting went in other directions, including abstract expressionism. Without totally obscuring traditional notions of subject, I was drawn to the idea that photography could also communicate intangible responses through abstraction. Peter Turner’s open-ended notion of ‘Objectless Space’ provided a title for the direction I was exploring through photography.

“I painted through much of the 1980s, Objectless Space never too far from the process. The work I produced during the late 1980s and 1990s was both digital and photographic, but not closely aligned to my early work. In 2001, I exhibited digital images in Mildura Palimpsest and paintings at the Mildura Art Gallery, separate events. The paintings were certainly informed by earlier photography explorations. The images I produced for my MA titled ‘If I Belong Here, How Did That Come To Be . . . ? were exclusively paintings. The images were formed by observations of the environment on a journey following the route of the inland explorers Burke and Wills in 1860/61. Rock, tree, sand, horizon, were the things themselves, without any attempt to paint the thing itself.

“In 2023 I exhibited photographs from a project titled ‘fLIGHT’ that have direct lineage to the work produced at Prahran almost 50 years earlier. This work was the culmination of images produced in the preceding 7 years.

“In late 2024 I commenced work on a project with the working title ‘Country Is In The Carpark’. This is an open-ended project. My visual and conceptual approaches to this project are closely related to the ideas and applications seeded at Prahran 50 years ago.

“Unfortunately, I can only imagine a discussion about this recent project with Athol, Paul and John, but their words and sentiments maintain a place in my life and creative process.”

6 thoughts on “Discussion: Abstraction”