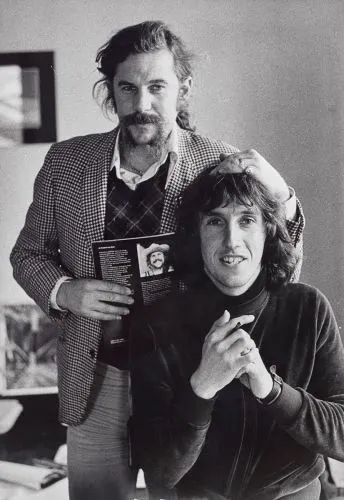

On Thursday 8 August 2024, at 6pm in Fitzroy Town Hall, Fitzroy 1974 by Prahran alumnus Robert Ashton was launched with an ‘in-conversation’ between Robert Ashton and Greg Day. Slated to take place in the Reading Room, in the event, the audience filled the capacious town hall ballroom, such was the interest in this book, a revival of a groundbreaking example of sustained street photography as practiced at Prahran College.

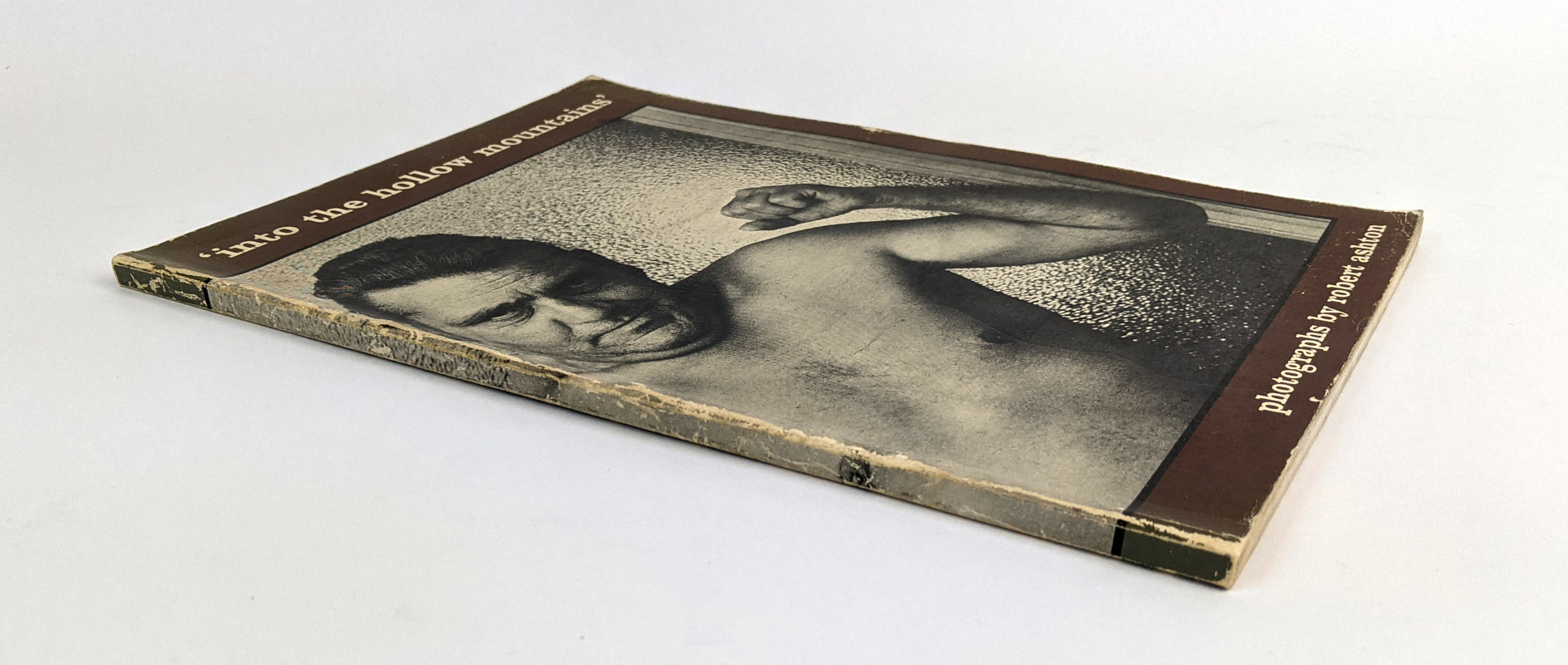

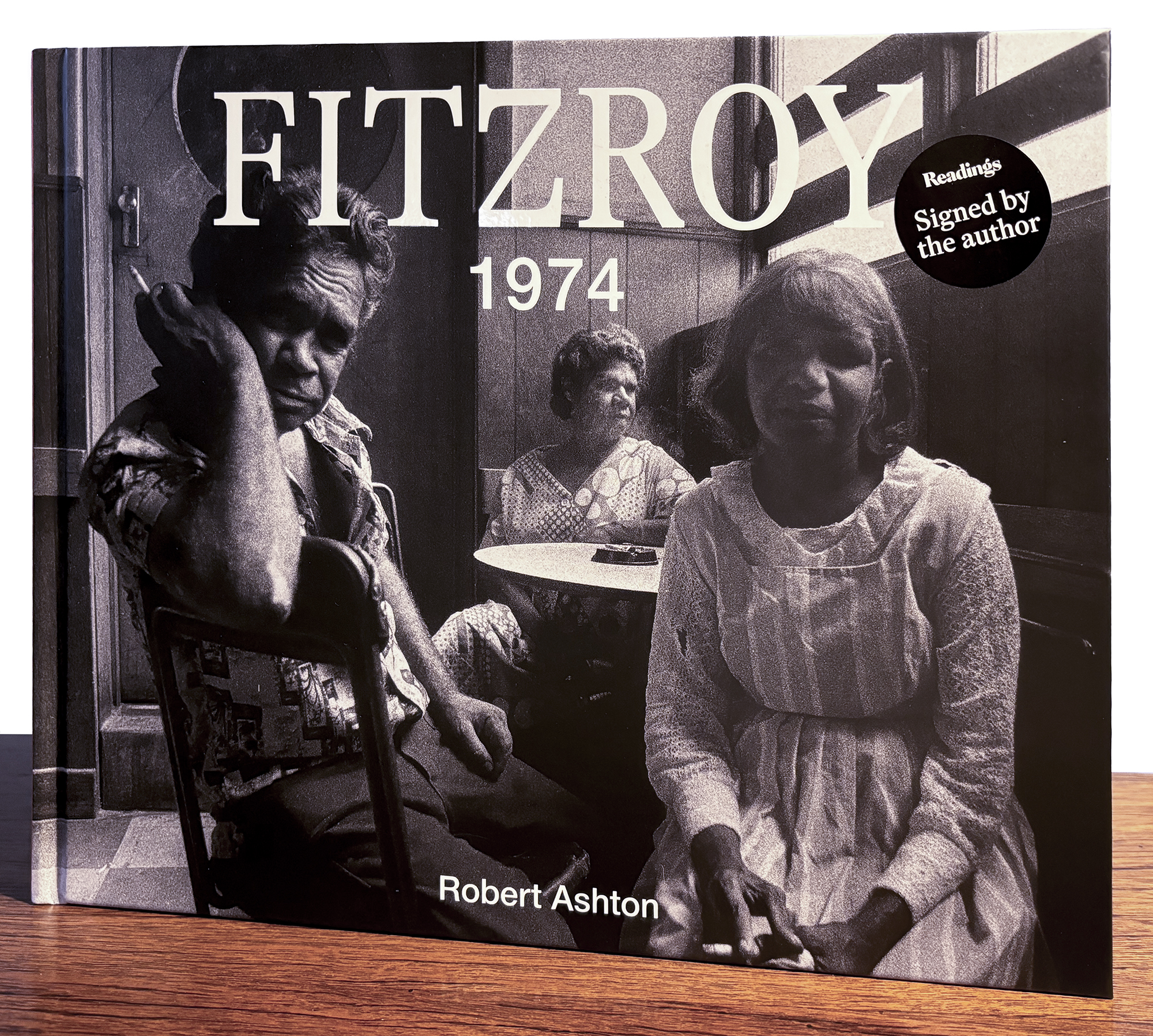

Fitzroy 1974 is a fresh, expanded and superior quality edition of his Into the hollow mountains which was early amongst the many publications of all kinds produced during their careers by graduates.

The opening address by Cr Edward Crossland, Mayor, Yarra City Council was followed with an introduction to the book by Sandy Grant, the CEO of Hardy Grant Books which published Fitzroy 1974.

Here is a transcript:

Mayor Edward Crossland: It’s my pleasure to welcome you to this evening, where we celebrate the launch of Fitzroy 1974 by Robert Ashton, a photography book that takes us back to the streets of Fitzroy in the 1970s. Originally published in 1974 under the title Into The Hollow Mountains, this landmark book features stunning black and white images captured by young Robert Ashton alongside original writings from local authors including Helen Garner.

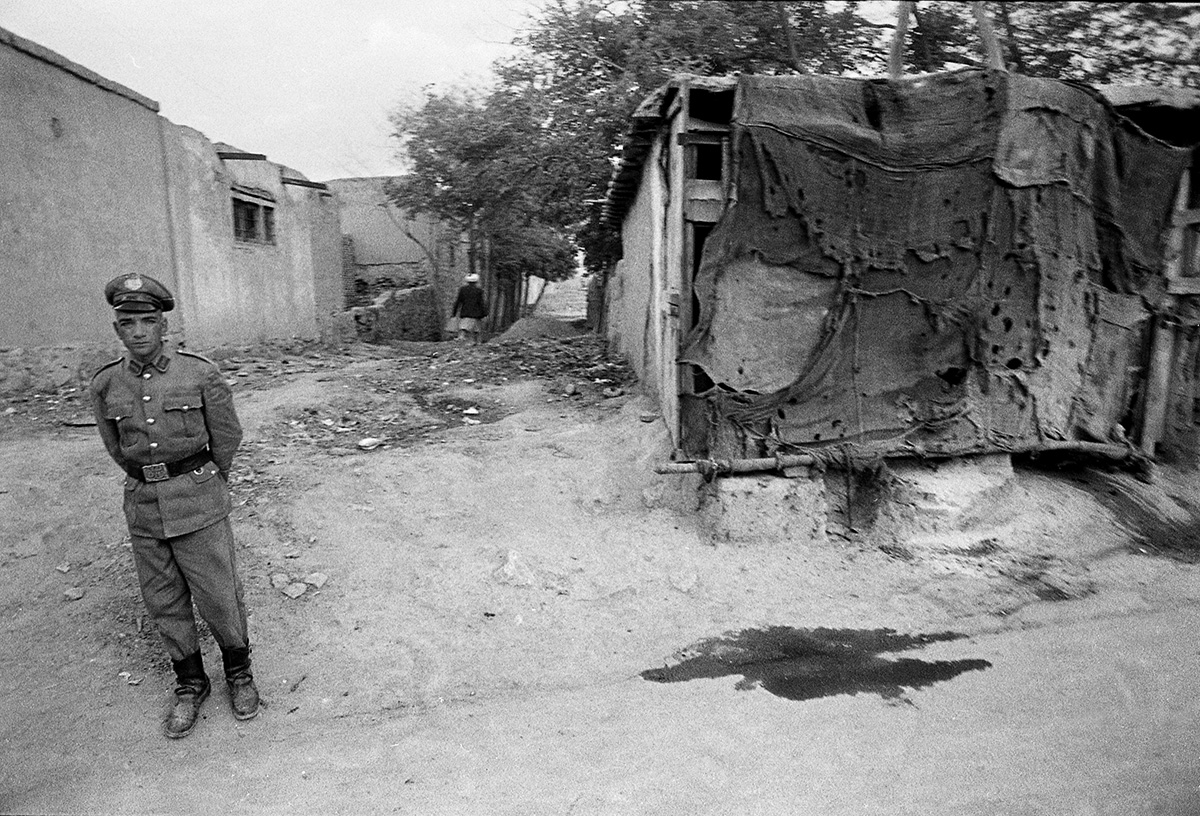

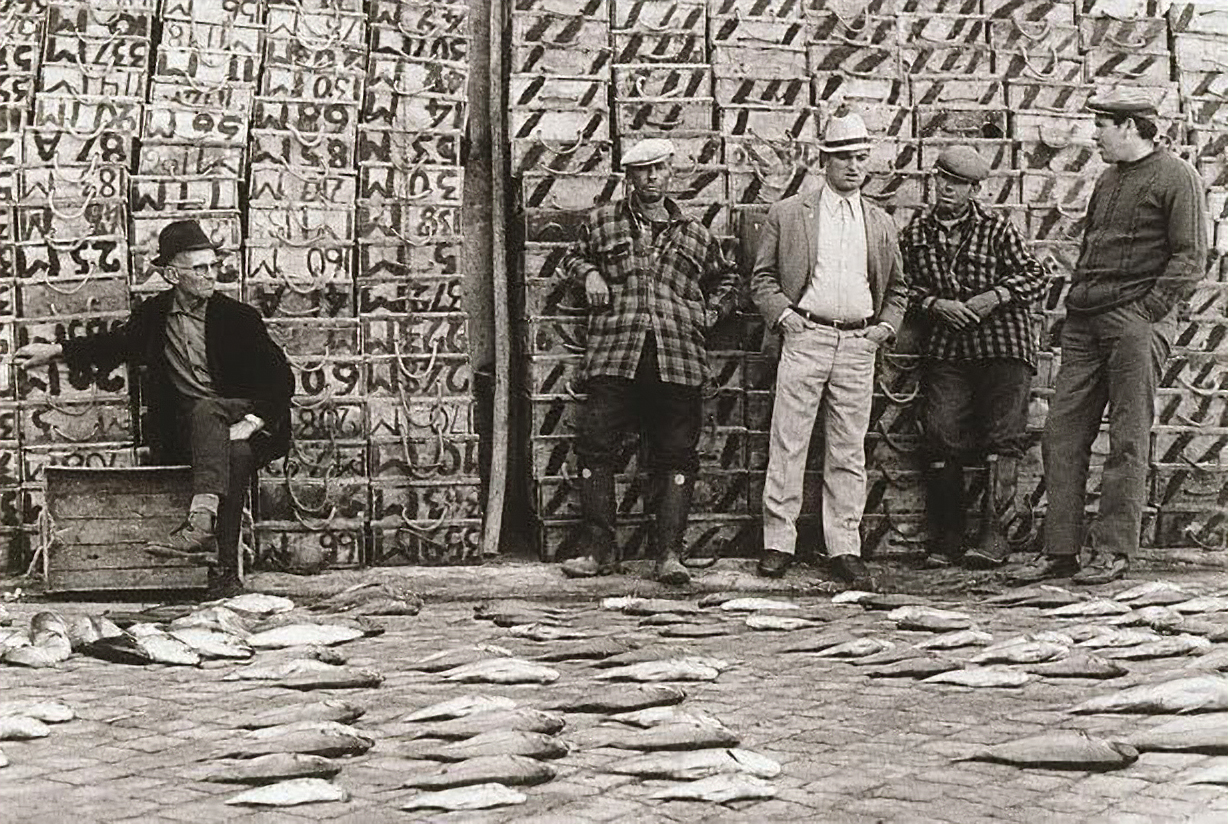

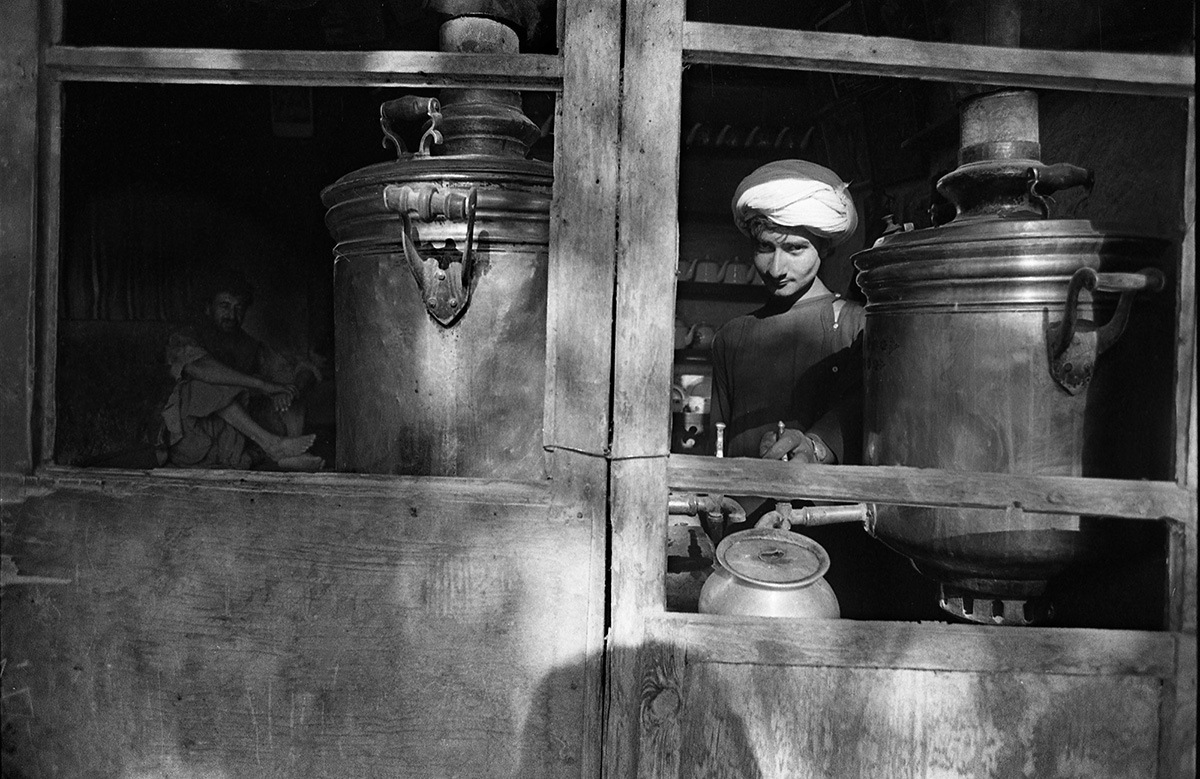

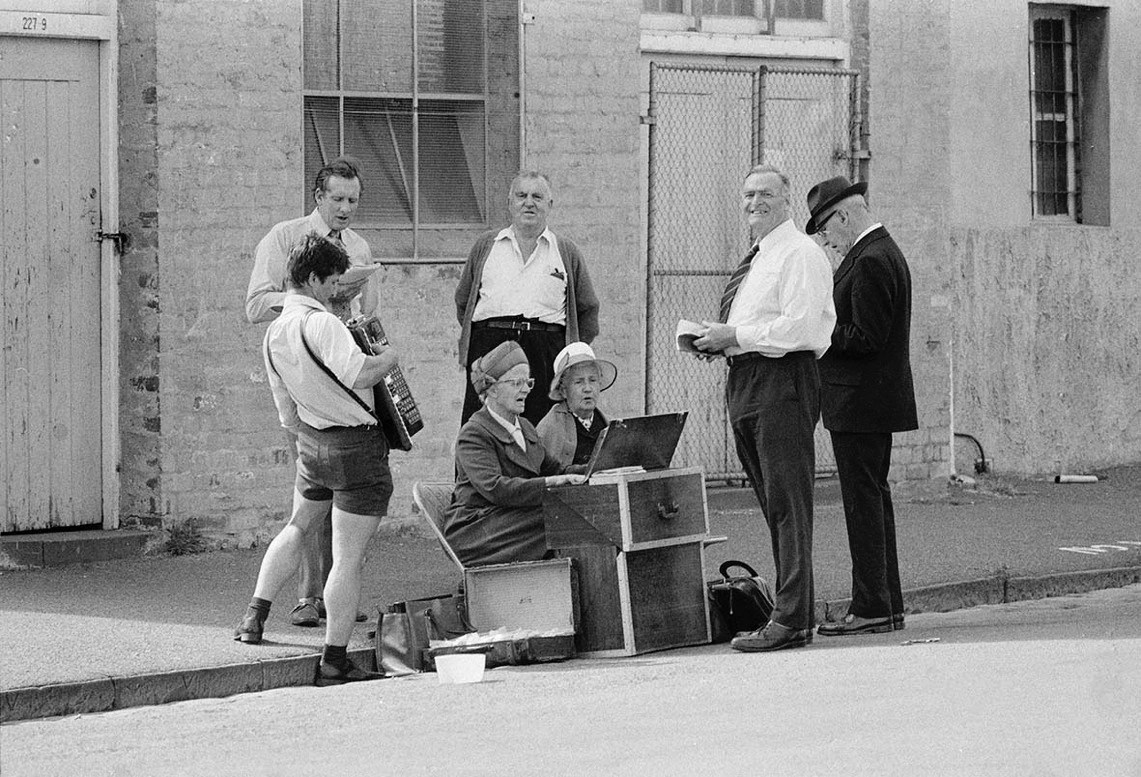

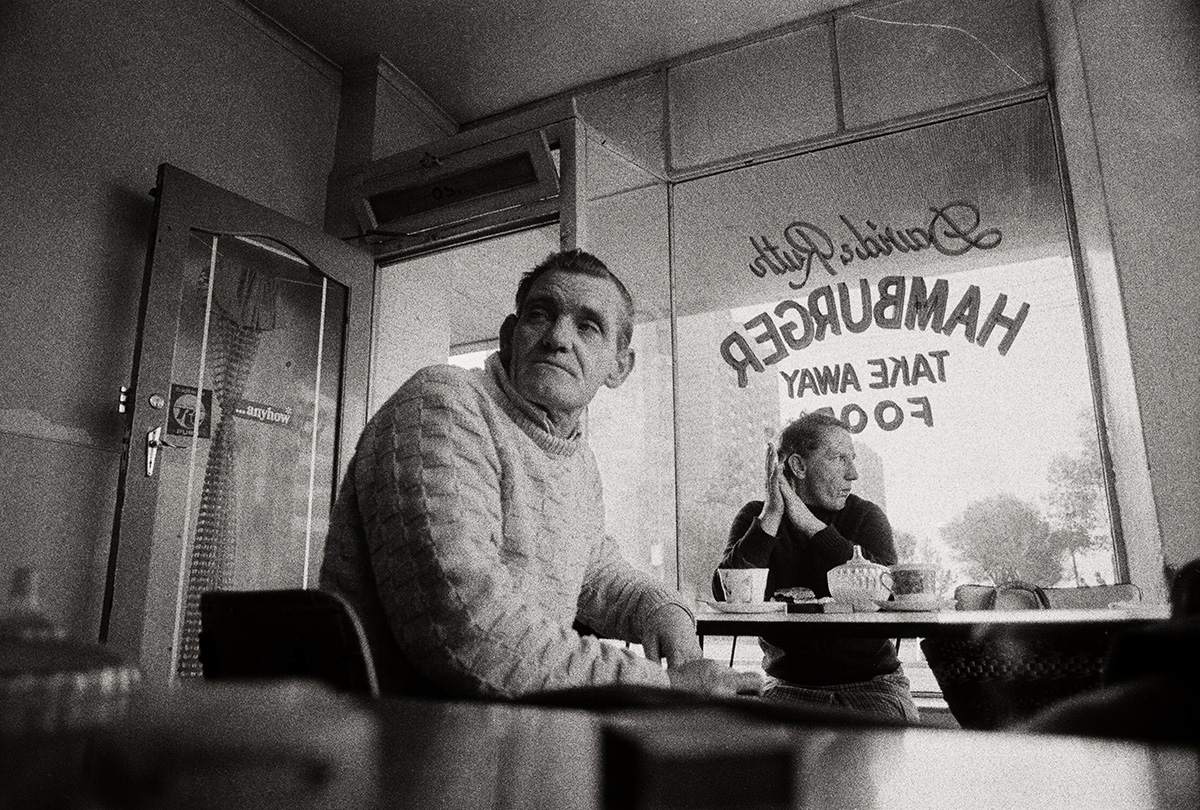

Fast forward to 2024 and Fitzroy 1974 offers an authentic record of life in one of Australia’s most diverse inner city suburbs, during a period of significant change. This book is a unique collection of over 100 images, showcasing Robert Ashton’s extraordinary eye for what makes Fitzroy special in 1974. Its evocative and compelling photographs provide a great glimpse into one of Australia’s most influential suburbs at a pivotal moment in history. From a historical perspective, the images capture the colonial roots of urban Australian, visible in the bluestone lanes and hard-case pubs of 1970s Fitzroy.

The suburb was vibrant with diversity, as children of migrants found their place among the high rise flats. The streets served as a sanctuary for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The cultural landscape, including Mother Teresa’s Sisters of Mercy, the Divine Light Mission, the Greek Orthodox Church, Protestant nuns, student flop houses and industrial sweatshops. Fitzroy became a haven for artists, musicians, writers and photographers, drawn by cheap rent driving a creative legacy comparable to Greenwich Village in New York and Montmartre in Paris.

The book also features beautiful writing from award winning authors including Greg Day, Tony Birch, Lorin Clark, Helen Garner and Damien Sharp. The diversity of the area is captured in images and writing, showcasing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples multiculturalism, and the beginnings of a Bohemian artistic population. Yarra City Council is proud to have acquired a suite of these works for the Yarra Art collection, currently displayed at Richmond Town Hall, and many of which I find to be very beautiful and something that’s very special to see when I am in the office.

We are fortunate to have Robert Ashton and the writer Greg Day tonight in conversation. After the talk books will be available for purchase as they have been earlier on, courtesy of Readings Books and the authors will also be available for signing copies. Thank you all for joining us this evening, and I hope you enjoy the discussion and the opportunity to delve into the rich history and the culture of Fitzroy 1974, Robert Ashton’s remarkable work. Thank you all.

Sandy Grant: I’m not sure that I’ll introduce them [Greg and Robert] as they will introduce themselves in a second, but I will say some things on behalf of Hardie Grant, and then pass to them.

Look, I’m really delighted to be here to help launch Robert Ashton’s excellent book Fitzroy 1974. As the Mayor said, it was published first in 1974 by a very young, Robert Ashton.

Reemerging now it does stand as an insightful and revealing look at the essence of Fitzroy 50 years ago. But it does more than that; it brings us characters that were largely unknown and largely unseen to the page, and brings us characters and scenes that are both really powerful and intriguing. At Hardie Grant we are very, very proud to be publishing Fitzroy 1974. It’s a book that brings the era back to life, and as the mayor said, things have changed dramatically. But the characters and the times Robert captured remain in the background of Fitzroy and may be the essence that still underpins Fitzroy today.

That is a tribute to Robert—he was in his early twenties— and he managed to gain the confidence of the Fitzroy community to let him into their homes and businesses, into the communal spaces, streets and family life. As you can see, they appear completely at ease, the photographer hasn’t posed them, he’s simply with them, and it’s one reason the book is so compelling and so successful.

Fitzroy in 1974 was not an obvious place for Robert to be accepted. It was a tough corner of town and somehow he connected with Fitzroy and I know some of those connections have survived and remain alive today, in a mutual respect between Robert and his subjects 50 years later.

In addition, having Tony Birch, Helen Garner, Lorin Clarke, Greg Day, some of the most prominent authors, contributing their writing gives the book some real depth and it gives us a contemporary context that makes the book all the more complete.

Robert now, 50 years later, is a significant figure in the photographic community. His works are collected by many of the major galleries. He moved really from photojournalism to photography as art though this is clearly art as well, and if you don’t know his work, I recommend you take the time to seek it out.

From 1974 Robert’s journey included opening one of Australia’s first photographic galleries Brummels in South Yarra with his cousin Rennie Ellis. That gallery had a huge influence on a generation of photographers and we can still see something of that now if you take yourself to the State Library, where there’s a fantastic Rennie Ellis exhibition on, that part of that covers Brummels and has Robert’s insider comments all over it, on how the works were conceived and executed.

Robert pretty much left the city in the late 70s, and his work since has covered a wide range of ideas, a wide range of subjects and used a great variety of printing methods, making his whole body of work impressively varied in style and tone and content. I think, and Robert might correct me, the closest work to his Fitzroy 74 is really his brilliant, evocative work done in India over many years.

We’re really proud to be able to bring the book back to life and I hope it’s embraced by both the current generation in Fitzroy as much as it will be welcome back to the print by those who that remember 1974. A final source of pride for me personally is that Robert happens to my brother-in-law , and I’ve seen up close his commitment to his craft, his extraordinary knowledge of photography, and I very genuinely believe his work deserves all the public awareness, credit and recognition it gets. Capturing this era in this book, and place, in such a definitive way is clearly one of his greatest achievements and its good now we are able to make it available to historians, Council and community in hardback covers for reference for the next 50 years or more.

So, I introduce Greg, who is a well-known poet, twice shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Award as a novelist, and a handy musician as well, and possibly a surfing friend of Robert’s. I welcome them both and invite them to take take over from here…

Greg Day: Thanks, Sandy. Welcome everyone, into this amazing room…cosmic Victoriana I want to call the ceiling. It’s fantastic to be here for such a such a great occasion…not your average book launch, not your average book, and I’m glad we’re on Wurundjeri land especially when the wattle blossoms are reflected in the river at the moment… I was walking by the river today, it’s always a great time of year.

First of all, I’d like to say to Robert, congratulations on a great book, and we’re all really happy and glad to be here tonight to celebrate it so…1974 is a long time ago really and a lot has changed around these streets since then. I was in a pub earlier tonight and they were charging five dollars for a single oyster. I mentioned that to Robert before and he said, in 1974 you would probably not have got any oyster and if there was it was probably Kilpatrick with bacon all over it; things have changed.

What I think we could do tonight in this conversation is to jump into a time machine and go back a little bit to the time of these images, and to talk about how this book happened and how Robert, like a working class bloke from Pascoe Vale, came to be walking these streets and talking to these people and rendering these images.

In 1974, when his pictures were taken, I was nine years old. I was reaching the peak of my football prowess for the Fitzroy Little league, as it happens, but you were doing something very different Rob, and to get into the background of that, I want you to tell us what you were doing in 1971 and 1972 that was setting you up as the person, the photographer, who could enter into this project.

Robert Ashton: I was from Pascoe Vale, another working class suburb not unlike Fitzroy. My brother went to art school, and I thought ‘that sounds like a good idea’, so I applied to get into art school as well. I got into Prahran College, moved to that side of the city and got involved in photography. Well, my grandfather was actually a photographer, a street photographer in St Kilda he and I knew little about him, all his works were lost, fell off the back of a truck after he died, but there must have been something in the genes that I got involved in photography, in a degree, a diploma at Prahran. There I encountered, as a huge influence, Paul Cox a filmmaker and photographer, and Athol Shmith a well-known fashion photographer and they had a profound influence on me. Paul was your genuine European black-clothed artist that I’d never come across before. They really taught me a lot about the formal aspect and the aesthetics of photography.

Greg: After you were in Prahran, you were into that European sensibility of the integrity of the formal image and particularly in black-and-white…

Robert: If you were involved in art photography up until the 70s you only worked in black-and-white. Fortunately, that’s changed, but that was the way was then.

Greg: Yeah, ok that was what was going down…

Robert: That was going down

Greg: You graduated in 1971, and then in 1972 you went traveling. And I think this is a key point of context for how you came to be taking these pictures in Fitzroy, as I understand it. So, tell me about 1972.

Robert: It was sort of life passage that when you completed whatever education you were doing, you went off backpacking. I went through Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East, Europe. I took a couple of cameras in an old plastic satchel that I had, and took photographs along the way. I took colour photographs which I thought might sell to a photo library, but really my focus was on the black-and-white work. I just roamed and learned to look and learned to interact with people. That was a huge influence and I exhibited that work when I came back.

Greg: You were in Marrakesh, you were in Tunisia, you were in Algeria, and in Portugal. You weren’t merely doing London, Paris…

Robert: No. Which you didn’t in those days. Nowadays you plot your itinerary on the phone and there are people to contact all along the way, while those days you collected your mail every three months at the American Express and you phoned home if you needed money … other than that you were on your own…

Greg: ..with a camera in your case…

Robert: With two cameras, which I left under a seat in a cafe in India where everyone had told me ‘they’re gonna take everything you own’. I forgot them, I ate, I left, and ten minutes later some bloke came running down the street, saying ‘you’ve forgotten these’. So that kind of taught me a lesson about trust and people, which carried through.

Greg: So you came back, And you moved into a share house in Prahran, with some people who were significant to this book.

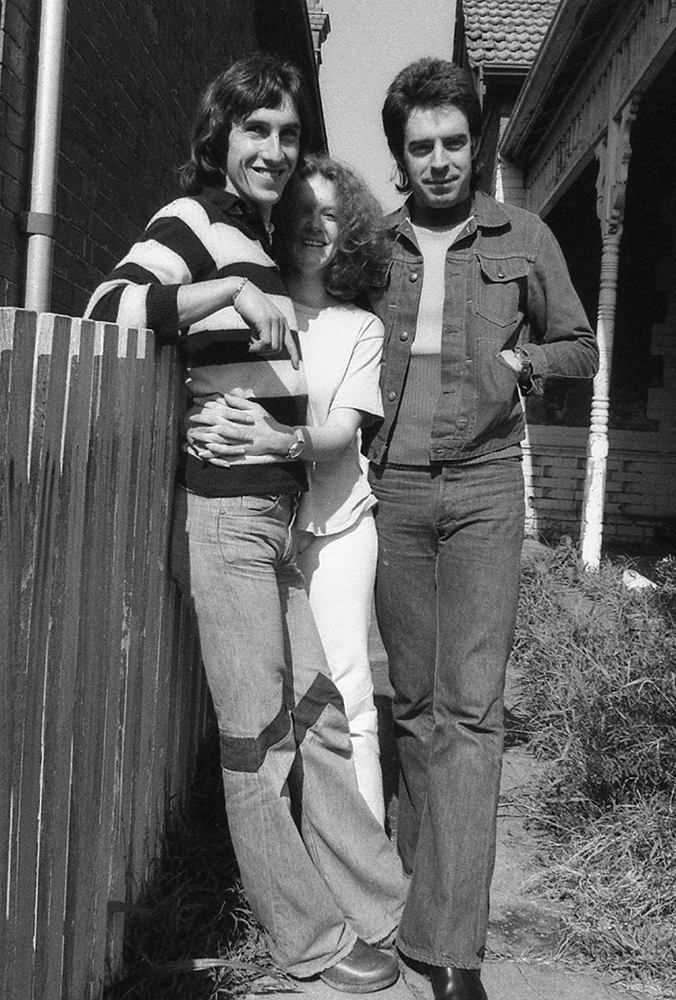

Robert: I moved to a share house in St Kilda, the infamous Mozart Street which I shared with Ian Macrae who I think is here tonight; Carol Jerrems, who became, arguably, a pretty prominent photographer…unfortunately, died early and left an amazing body of work; and Mark Gillespie the musician. We shared that house together.

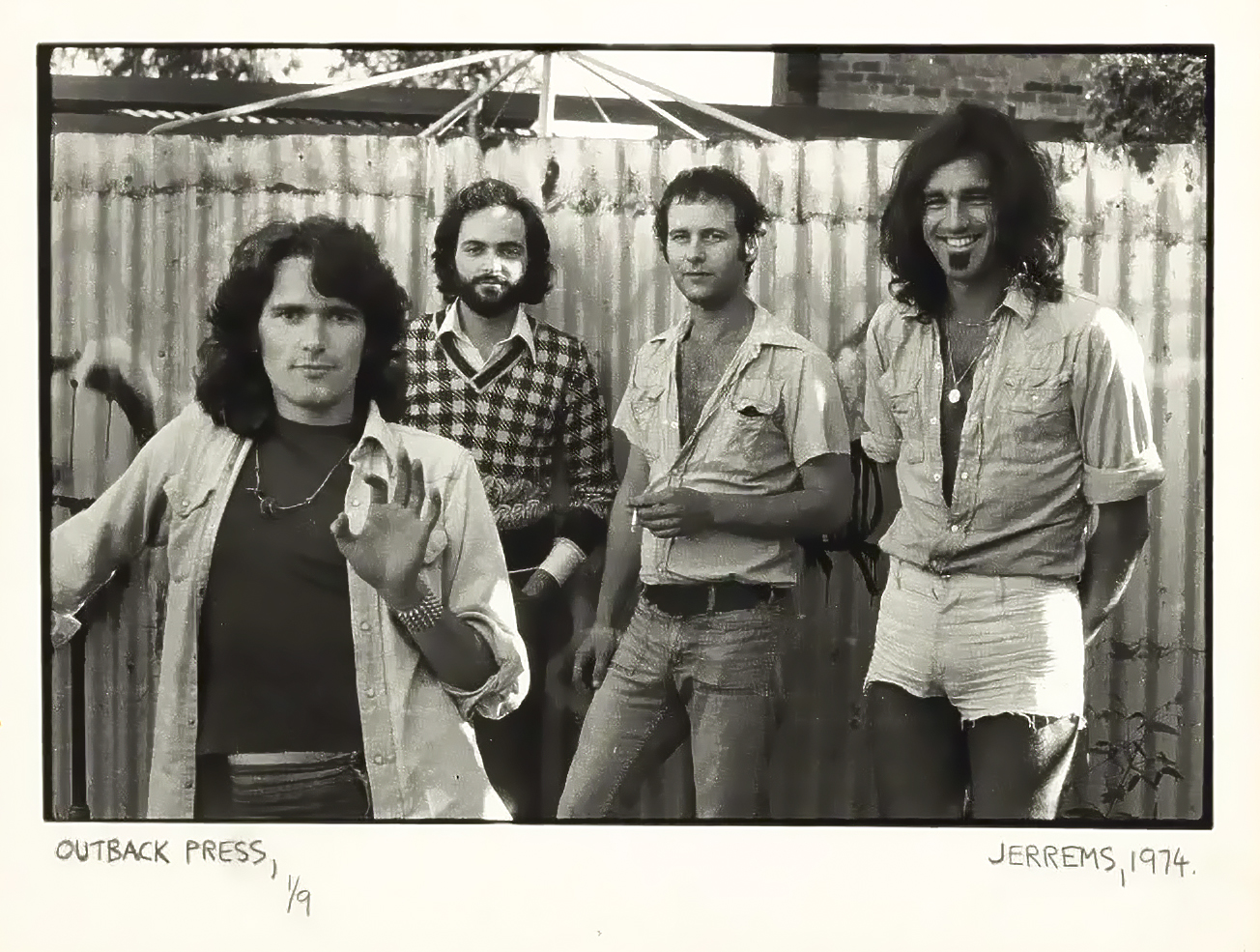

Greg: Mark Gillespie was involved at that time in starting a publishing collective called Outback Press.

Robert: Yeah, Outback Press which he started with Morry Schwartz, Colin Talbot, and Fred Milgrom. They started this publishing outfit with the aim to publish Australian content, and it was Mark’s idea and inspiration to do the Fitzroy book.

Greg: …and they also did the book A Book About Australian Women with Carol, Carol Jerrems, and a book of Australian women’s writing called Mother, I’m Rooted

Robert: They did, and a number of other books.

Greg: This is the Whitlam era, we’re talking ‘73?

Robert: Yeah, things were pretty…open-ended, creating the idea that anything is possible. That was the field.

Greg: Mark Gillespie had this, idea to do a book on Fitzroy, and he came to you, and asked you to be the photographer. Was there any particular reason apart from the fact that he liked your work?

Robert: I would say, because I was there, which is the way a lot of things happened in those days. Carol was there, I was there. We were hanging around together. He thought…he’d seen some of the work, but not a lot…he said ‘do you want to have a go at this?’

Greg: You said ‘yes’, and there was no money involved, anything like that?

Robert: No, no money involved, with no real parameters; he had some ideas, he’d spent some time around there, he gave me a few leads to go here or there, but basically he said go and see what you see.

So I spent a year traveling across to Fitzroy in the old Beetle and spending my days wandering the streets and seeing where it took me.

Greg: In Tony Birch’s fantastic essay in this book, he describes the lineage of photography in Fitzroy up to the point when you arrived at the scene. It’s very stark kind of picture which basically involves what Tony calls social reformers and religious zealots with a condescending, patronising attitude trying to save these poor people that lived in Fitzroy. But you came without that agenda and perhaps without any agenda in that sense.

Robert: No, no agenda. I didn’t really know a lot about Fitzroy, but I had spent that past year traveling all over the world, and I’d become more comfortable moving in all sorts of different milieux and I also came with this formal aesthetic training. I went to see what I could see, and I would point my camera around, and I was always looking for ‘the shot’; I was looking for the composition, and I was letting whatever passed in front of the camera—or whoever—pass in front of the camera.

Greg: One of the striking things about the book and these images, which, you know, some of which were in Into the Hollow Mountains, the book that Outback Press published — in this book, of course, there are many more images. One of the striking things, of course, is what they call in academic circles, the gaze of the people who are in the pictures. There’s, not always, but in most of these pictures, the people, you’re photographing seem very happy a lot of the time… there’s lots of smiling and kind of relaxed views. There’s lots of interaction between people in a jovial sense, an ironic, jovial sense. There’s a sense almost that you are not there as a photographer, almost like it’s an expanded family photograph of the times even though you’re bringing this formal expertise to the image, as you say, and that Mark Gillespie had this idea… to document something; tell us something about how that came to be. You’re on the streets, you’re with kids, you’re with the Sisters of Mercy, you’re with the Koori community in the pubs; how did that come to be?

Robert: I think it helped that I had no agenda and it helped that I was sort of young, you might even say ignorant. I was open to whoever I might meet and there was a feeling of trust out and about which may be, doesn’t, isn’t as evident these days. I felt free and open to go and approach and people said no, but not very often. Most of them, they said ‘yes’. And one thing led to another, led to another.

The pubs were pretty scary places, so they said, in Fitzroy. I thought, ‘well how am I going to get into these places?’ I went into the Builders Arms Hotel and there were a few First Nations people in there; it was a place for meeting. People welcomed me, they were warm, they took me under their wing. There was a pretty well-known family called the Lovetts in Fitzroy at the time, and a few of them were in that pub. They took me under their wing and said ‘if you want to go to the Champion Hotel, fine, let’s go’, so I had an escort and an ‘armed guard’ if you like. That sort of thing happened on a number of occasions which made the whole thing a lot easier. The only time I felt even a bit threatened was in the Champion Hotel, but I was well guarded and there was no problem, but generally people—and I think you can see in the pictures in the pubs and things—were happy and engaged. It was in the era before, people worried about surveillance and that sort of thing. There was a certain innocence in that way. People were open.

Greg: It was also a time—I started living in Fitzroy in 1984 I think, ten years later—but in ’73, ’74, this was right on the cusp of a transition, which you can call gentrification, you can call the arts, kind of kicking off big time in Fitzroy. And that’s part of the book as well, that a layer of these people like, Danny Robinson, the musician, you photographed him, Joel Elenberg, the sculptor, Sweeney Reed…there’s this layer as well that you’re walking into the studios, early days, which, you know, ten years later when I rocked up, that was when it was well and truly flourishing.Tell us about that as well.

Robert: ’74 or around that time it seemed like kind of a pivotal moment of change, because for want of a better word the old Fitzroy was there, and the new Fitzroy was moving in. There was a lot of action around the council flats, a lot of action in the pubs, in the cafes, the Greek and other European communities, First Nations communities, your old style regional Aussie working class families a huge mix.

The Sisters of Mercy were there. They invited me to their place. There’s a funny story about that. I got into where they were. They were helping a few of the less fortunate people there. I took what I thought were some great pictures, took them home to the darkroom in Mozart Street, which was a communal darkroom, processed them, and buggered it up for some reason; I wasn’t very good technically. The processing was a mess. I threw it in the bin and left. Maybe half-an-hour later one of the other residents went into the darkroom to process some film, found the work, washed it, hung it up, and out came some of the more powerful images in the book, from it. I’m grateful for that.

Digital technology has helped me in that way. I might say that all the pictures are full-frame and and haven’t been fiddled with, [except] to the point where some of these negatives were scarred and broken, and I was able to resurrect them, which was good.

Greg: The book came out, Into the Hollow Mountains, and you hated the result at the time. Tell me why you hated the result.

Robert: I don’t think the publishers are here…[laughter]…I was pretty young and naive. They launched the book in 1974. I went to the opening. It ended up chaotic, somebody came in and pinched a lot of the books, took them outside to distribute to the people of Fitzroy, and the people who put on the opening ended up closing it down…probably the only people that got thrown out of their own book launch!

But the quality of the printing was such that…I’d been drilled by Paul Cox and the fine artists about the fine print, and these were like newsprint…I discarded the book and had forgotten about it for many years because I was distressed at the reproduction. Now it’s become a historical and cultural thing, but in those days I wanted to see my pictures looking good; I discarded it for 40 years. Then someone came to me, maybe ten years ago, found the pictures and said, let’s have an exhibition, which I had at the Colour Factory here in Gore Street, Fitzroy, and I started looking at them again and others started looking at them again, and the journey to this book started.

But the quality of the printing was such that…I’d been drilled by Paul Cox and the fine artists about the fine print, and these were like newsprint…I discarded the book and had forgotten about it for many years because I was distressed at the reproduction. Now it’s become a historical and cultural thing, but in those days I wanted to see my pictures looking good; I discarded it for 40 years. Then someone came to me, maybe ten years ago, found the pictures and said, let’s have an exhibition, which I had at the Colour Factory here in Gore Street, Fitzroy, and I started looking at them again and others started looking at them again, and the journey to this book started.

Greg: After that whole thing there’s a sense now that you’re seeing the pictures the way you want them, the way you were imagining it when you were given the documentary brief by Mark but with your own formal aesthetic…now you’re seeing it…

Robert: Absolutely, and I had the good fortune to be able to go back to all the original work and see things that I hadn’t seen before. This book is, you know, hugely expanded from the first book. I feel fortunate to have been able to do that. Yeah. And I’m happy to see them now, as I intended them.

Greg: Because these photos exist, and because of the nature of them, there’s been great connections with people through them that it’s happened since then?

Robert: Well, that’s the one of the other great things for me. I’ll give a shout out to Karra Rees from Yarra council who’s involved in another project to put together a book of First Nations people in Fitzroy. She ended up tracking down a number of those people who were in my images and putting names to the faces, which meant an awful lot to me; I made connections that I had never even thought about in the past.

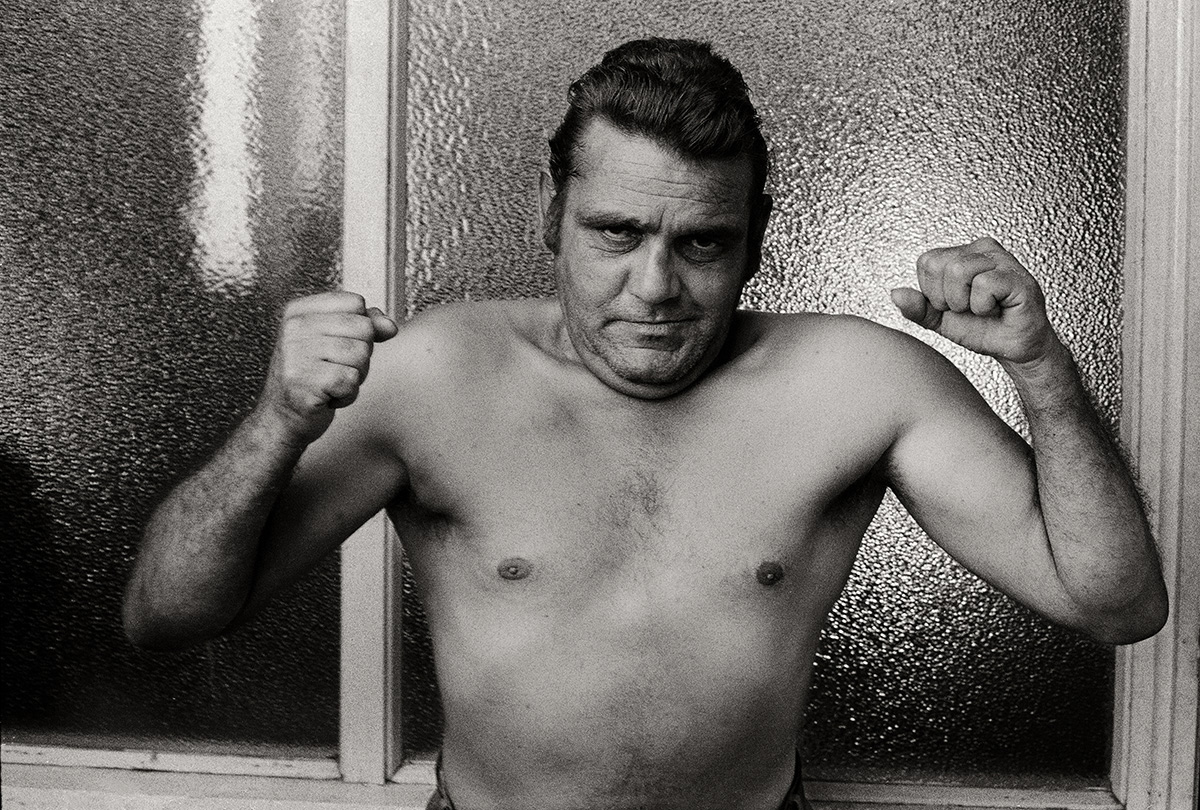

On the front cover of the book is a man called Cecil Coombs. His brother is Kevin Coombs, who is a very famous Paralympian athlete. He saw the images of his brother just before he died recently and gave me permission to use them; that meant a lot to me. On the back cover is the strongman and his name is Allan Lovett, and I was very fortunate to meet his son a couple of years ago who’s Allan as well, who also, was pleased to be able to share his story and make that connection with him. And as a postscript, I was fortunate enough to take the portrait of Alan Jnr. in the Builders Arms a couple of months ago, exactly where his dad was, but it looks a bit different these days. That’s where you get your oysters for five bucks.

Greg: Yeah, five dollars. In Lorin Clarke’s piece in the book—one of three essays in the book— the last paragraph of Lorin’s piece, she describes (this is probably last year when she wrote the piece) she describes walking home along Brunswick Street one night. It’s a bit quieter than usual, and she glanced up at the second storey of an old terrace on Brunswick Street and saw a person sitting in the window. As she looked up—she’d been immersed in your photos at the time—in her piece Lorin talks a lot about how the seeds of what she understands is Fitzroy, someone who arrived from Greensborough in the ‘90s, the seeds of that, she could see in your photographs.

Anyway, she looked up at this person in the window frame and she thinks ‘it’s just like a Robert Ashton photograph’; there is a stillness and a solitude, but within the community, it’s like outside, and inside, on the street, visible, and she waved and he raised his teacup to her, and I thought it was a beautiful moment!

This isn’t only a historical book; the life in the photos, the energy of the people in the photos means that it feels like yesterday or tomorrow at the same time. That’s something that we can say about your work in these photos is that somehow you’ve managed to capture the solitude in people as well as members of the community, in the people, and that’s not something that you see every day, and it does transcend time in a sense. That’s a great thing.

I welcome everyone to applaud this book and let Robert that we’re all here, and it’s a great achievement.

Robert: Thank you everyone. I talked about the openness of the community back then and how things have changed, maybe the more things change, the more they stay the same. You could probably find the same things, in a different way, right now, if you were a young bloke or a woman wandering the streets…it’d be interesting wouldn’t it?

Greg: To finish off, we thought it might be a nice idea if you were to read Mark Gillespie’s little piece of writing, an edit from the original book Into the Hollow Mountains, if you would read Mark’s piece that is included in this book. He was the germinator of the project…

Robert: He was, he was the inspiration.

Greg: Mark is no longer with us; it would be nice to hear that as a tribute.

Robert: There was a lot of writing in the first book, a number of different pieces, a couple that have been included in this new book, a lot of others haven’t been; worth a read if you can find a copy of it, there’s not that many around. Mark wrote two pieces; one was called Micky one, one was called Micky Two, and this is the last paragraph, which summed a few things up for me. He says,

“but it’s not all pushing a pram around Fitzroy, so Micky and Bill decide to spend some time relaxing, getting away from the drab city at the residence of a musician friend, a violinist who plays with rubber gloves on…there’s going to be music in the hills.

The moving truck bounces along with the prams, armchairs and gramophone, Micky singing and clutching onto his silver kitbag and his safari hat, past the La Mode stack and the spray painters changing colours with every car. Lizards. A Perfect Cheese truck whizzes past and they are gone, further north Norma with her towering bouffant jet-black hair and stocking spider legs, leaves home in a tram that rattles up Brunswick Street, past the towers of Babel, past the Ace Billiards factory, the Rob Roy and back into the hollow mountains.

Greg: Thanks Rob [applause]

Robert: I want to thank you Greg, for the work that you’ve done, and the support that you gave on this book. I want to thank Tony Birch and Lorin Clarke for the great pieces that they have written. I want to thank Hardie Grant for finally publishing it for me, Pam Brewster, Todd Rechner, Kirsten Grant, Morry Schwartz and Outback Press for giving me the opportunity to start with, Mark Gillespie for the inspiration, Kara Reeves for joining the dots, Laura and Helen for personalising things and telling me their story, and Jane [Grant] for everything else.

Thank you.

The ABC makes available online an interview by Trevor Chappell with Robert Ashton about Fitzroy 1974 that was broadcast on 18 July 2024.