Graham Howe is one of the most prominent of Prahran College graduates. As an early promotor of the ‘New Photography’ through his book of that name, and while in his role as director of the newly formed Australian Centre for Photography, in 1974 Graham made contact with Gael Newton who was foundation curator of photography at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (1974-1985) and now internationally acclaimed as Australian art historian and curator specialising in photography across the Asia-Pacific region.

Formerly the senior curator of Australian and International Photography at the National Gallery of Australia, and recognized for her dedication to preserving photographic history, she established landmark collections, including 4,000 colonial-era Indonesian photographs. Now an independent consultant, Newton remains a leading voice in the arts and humanities with a passion for visual storytelling.

Gael, one of the essayists for MAPh’s current exhibition, has authored the introduction to Howe’s book, a considerable honour, given her stature as a historian of photography. The book is timely in its release as it covers the years 1970-71, Graham’s time as a student, and it can now be found alongside The Basement book in the Museum of Australian Photography shop as the exhibition of Prahran alumni of 1968-1981 continues.

I bought a copy so that I could review it here and it’s certainly not a purchase I regret; Graham’s business Curatorial in Pasadena, California is responsible for a fine production with a black linen cover embossed to resemble the sprockets of a roll of 35mm film and titles in a typeface like the factory-exposed film edge numbers and text, complete with the delta arrows.

Look closer and you’ll find that the images on the ‘proof sheet’ have been set individually into embossed rectangles as individual ‘frames’. Open the cover and you will find this theme is continued with proof sheets reproduced on the endpapers and text pages black with white type in the same typeface.

The crisp, tonally nuanced digital imaging of the now 75-year-old negatives is by Bjarne Bare of Curatorial, the design by Pidgeon Ward of Melbourne who produced the catalogue for early eighties Prahran alumnus Peter Milne’s Lovers and Misfits which was exhibited over 2022-23 at MAPh. Offset printing and binding is by KOPA in Lituania.

Gael in her introduction writes that Graham’s Epoch is a retrospective of his images and memories as an undergraduate art student at Prahran College between 1970 and 1971; important because Prahran, at this time, was a nexus for the ‘New Photography’ movement in Australia, bringing to our country international developments from the 1960s, the candid, loosely structured photographic language that contrasted sharply with the rigid narratives of photojournalism and the increasingly commercial aesthetics of colour photography. Within this context, Prahran’s commitment to black-and-white photography reinforced its distinction as an institution valuing interpretative and fine art approaches over commercial practices. This book’s production therefore beautifully supports that impression.

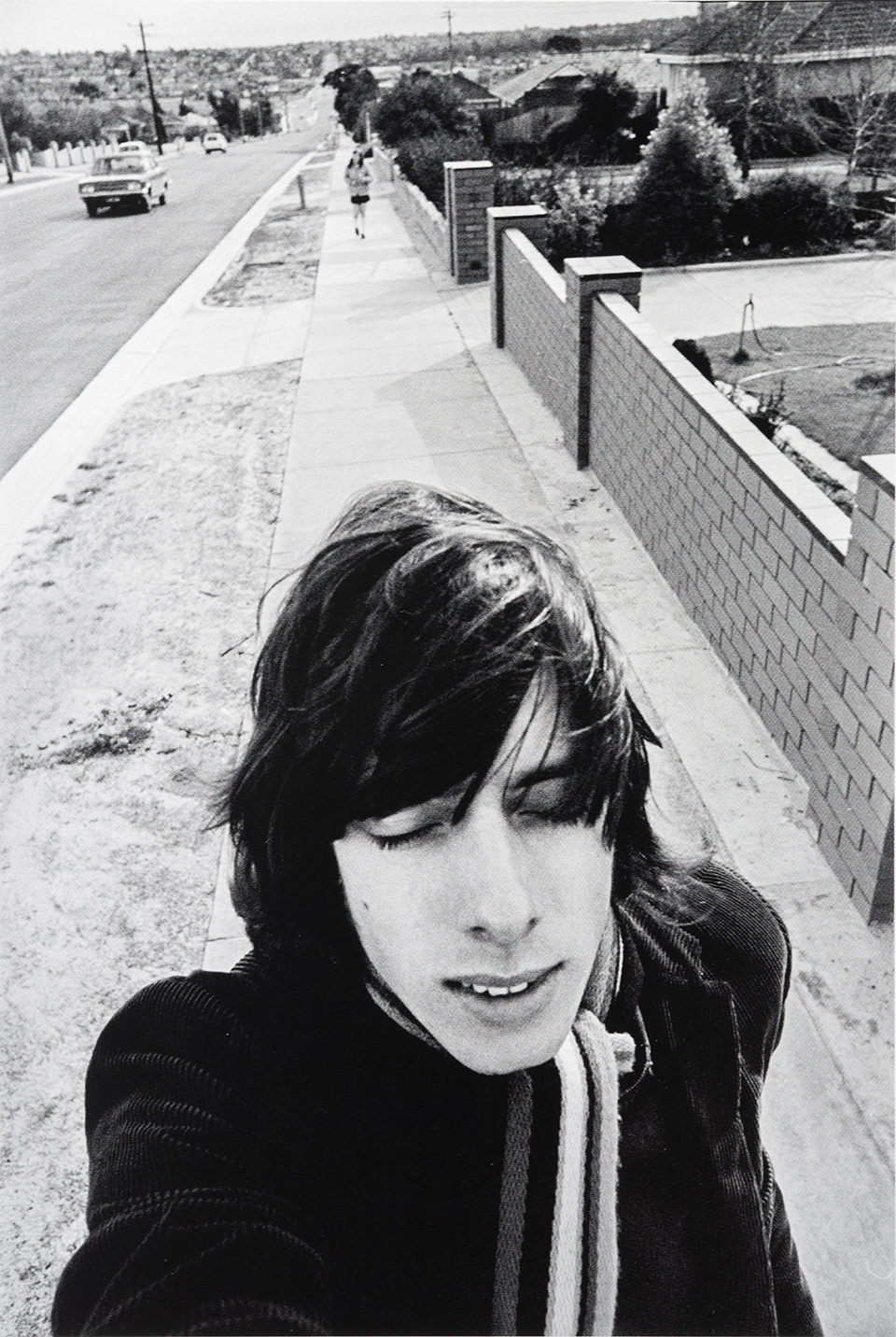

Howe, born in Sydney in 1950 and educated partly in Singapore, returned to Australia with an outsider’s perspective that, Newton argues, sharpened his sensitivity to Australia’s rapid socio-cultural shifts. It enabled his capture—through intimate self-portraits and domestic scenes, to dynamic street photography—of the personal and collective search for identity of youth between the tensions of conservative traditions and emerging progressive ideals.

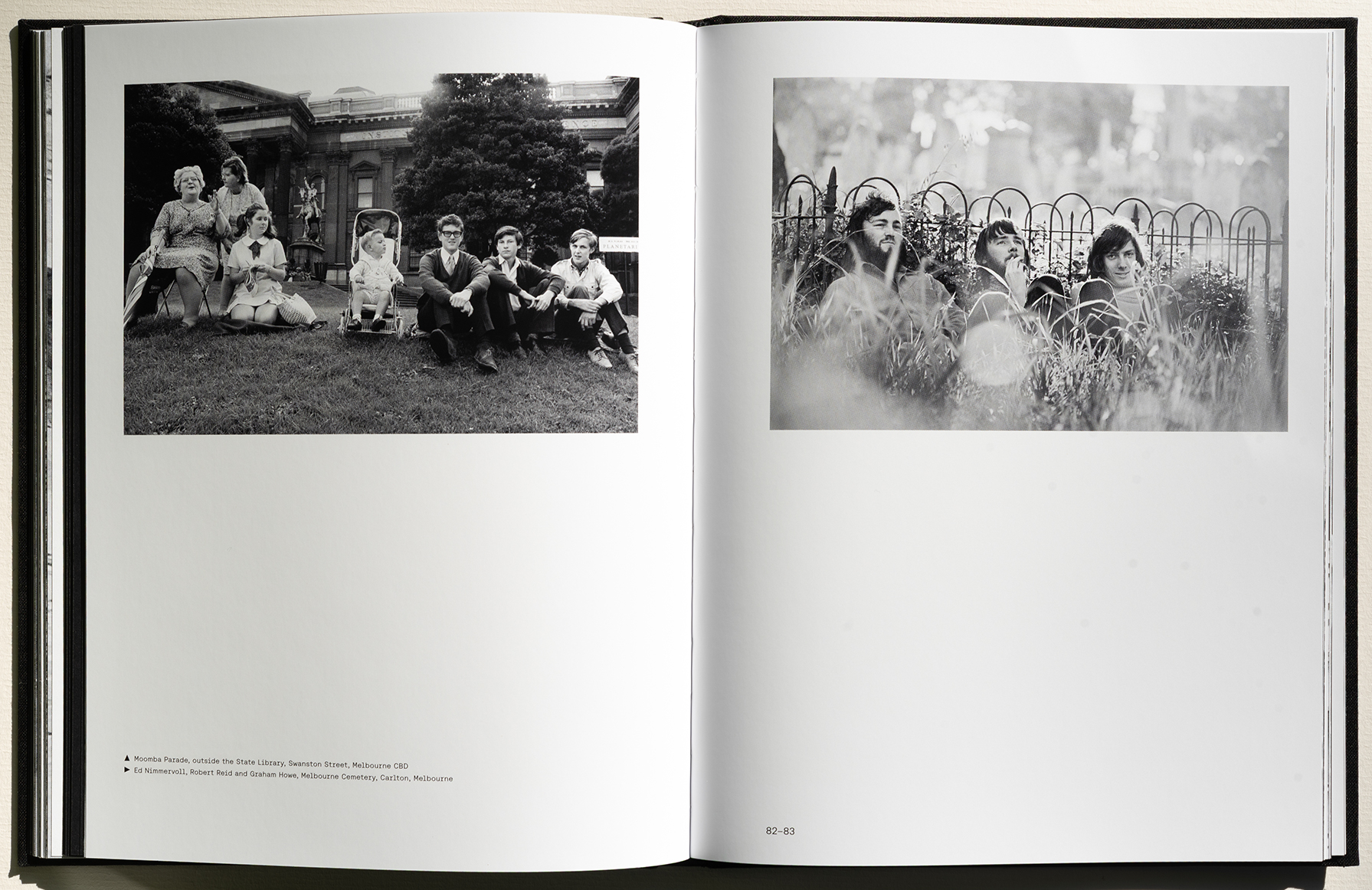

A heightened political awareness born of opposition to the Vietnam War fed the broader countercultural movement. Howe’s depiction of anti-war protests contrast with the Moomba Festival as visual manifestations of the era’s ideological divides and as Newton writes:

“stands out as some of the best photography of the era. Particularly poignant are a portrait of a young Vietnam War veteran at Gordon Place Men’s Home (page 106) and a young woman protester wearing a bowler hat and peace symbol”

Prahran College itself played a critical role in the legitimisation of photography as an art form within Australia. It spearheaded the integration of art photography into tertiary education curricula, fostering an environment where young artists like Howe could experiment formally and conceptually. Influential figures such as Paul Cox, one of Howe’s instructors, epitomised this environment of creative rebellion and intellectual engagement.

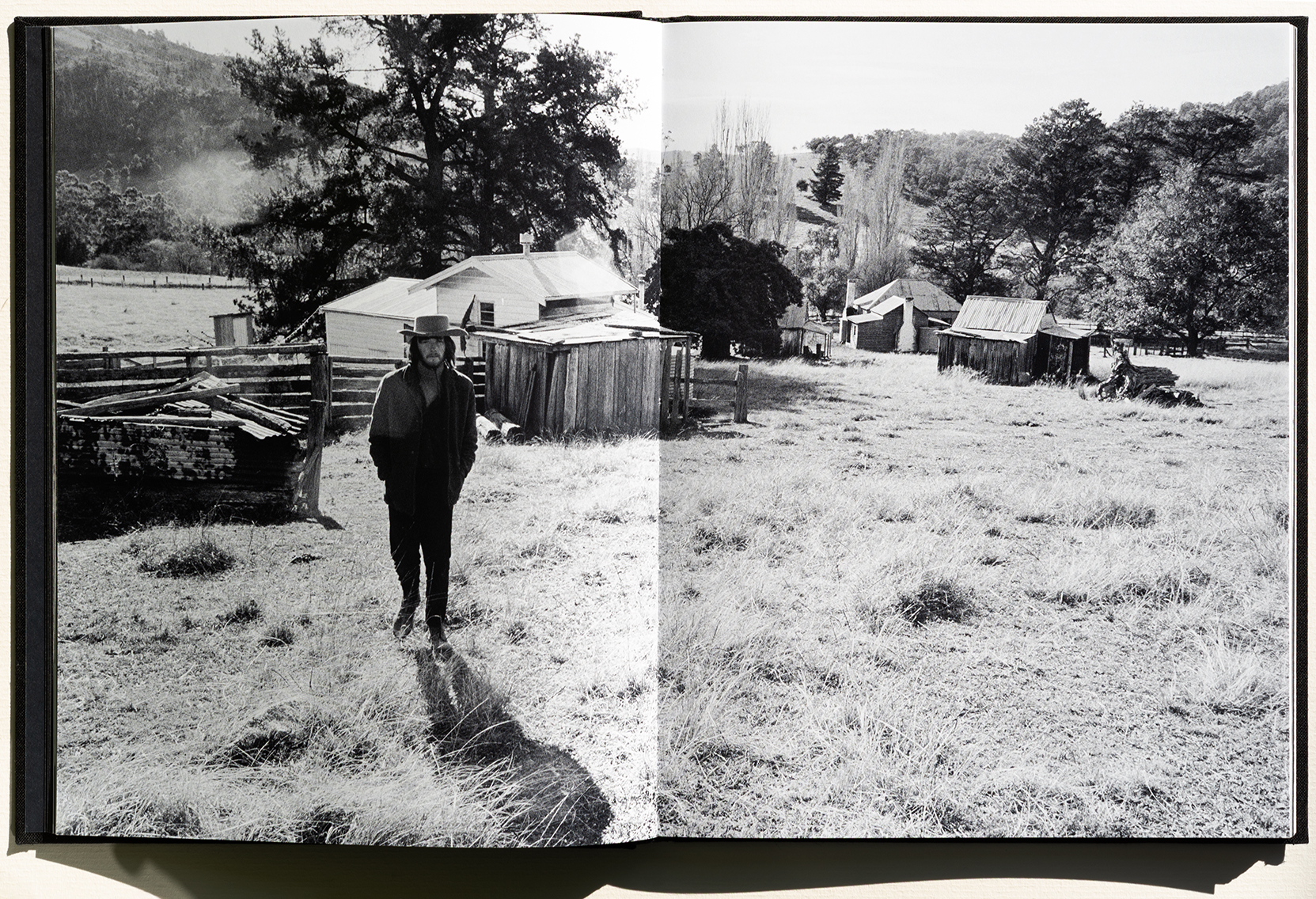

Newton finds in Howe’s early work a keen formalist sensibility—evident in his compositions and his acute awareness of light and spatial relationships—in an unselfconscious engagement with vernacular subject matter, from rural architecture to everyday urban life. His occasional playful juxtapositions, such as graffiti in public spaces, reveal an emergent intellectual curiosity about perception, context, and visual irony.

Newton points to a photograph featuring the wire finder of a Zeiss Ikon camera framing a wild landscape as symbolically underscoring these preoccupations, a singular, emblematic instance of Howe’s exploration of perspective and framing.

Epoch, Newton concludes, offers a deeply personal document of a formative period in Howe’s artistic development while encompassing broader transformations in Australian culture during the early 1970s.

It is Newton who carries the weight of historical and biographical content, and the visuals and their brief captions provide the main content, while Howe, in a middle section on black pages, summons impressions from his memories of the period, writing short essays of two- to four-hundred words in an acute style, on his Singapore education; amusing attempts to become hirsute like his hippie companions; the Vietnam war and conscription; the counterculture represented by the books being read; and the music; he touches on his time at Prahran and concludes with a survey of the international cinema of the early seventies (the longest passage). Howe’s brief essays, as he points out, are like ‘snapshots’ of the ‘epoch’, a particular period in his life delimited by his time before he moved to London to the Photographers’ Gallery and then to the newly opened Australian Centre for Photography.

Clearly they are edited to the bare bones, and a rhetorical contrast using paired semicolon-linked clauses appears at least once in each of this short essays: “…more than a school; it was an outpost of the British empire”; “… the mainstream ideology was clear-cut; communism was a threat…”; “The Whole Earth Catalog wasn’t merely a book; it was a manifesto of self-sufficiency”; “Going vegetarian wasn’t simply a dietary choice; it was a stand against overconsumption”; “They weren’t just books–they were guides…”; “this was more than rock; it was an eclectic mix…”; “That era, that music, was more than just sound; it was a way of seeing the world, of questioning boundaries…”; “Prahran College was more than a school; its was a sanctuary for those who saw the world differently,…”; “Prahran wasn’t just progressive; it was fearless.”; “This wasn’t simply art for art’s sake—it was art as exploration…”; “The college’s blend of of traditional and contemporary techniques didn’t just give us skills; it gave us perspectives,…” Such correlative conjunctions have their use in persuasive journalese, but constantly repeated here they become an irritating affectation, and in most cases the second clause would suffice to make the point.

The task for the editor, Claudia Sorsby was to fit text around what is essentially a ‘photobook’ format intended less for reading than looking, so the short essays are honed, insightful and incisive and will jog vivid memories for those who lived through the period and sketch the zeitgeist for those born since.

Most pictures are populated, but apart from their names in the captions, human characters are largely absent from Howe’s narrative. Yes, this is a biographical book of personal photographs—with six self-portraits if the back view, p.121 is counted—but our curiosity about the personalities with whom Howe mixed will be left unsatisfied.

Paul Cox’s influence is acknowledged, but the double-spread snap of him and his girlfriend mugging with their noses pressed against a milk bar window is only given significance through Newton’s interpretation.

Its caption is incorrect however; read the image closely and you will see that this shop (now a supermarket) is not in Punt Road where Cox had his studio, but in Sturt Street South Melbourne opposite Regent Motors’ outlet (now demolished) at number 86—it’s reflected in the window, as are parking meters and tram tracks, neither being present in 1970s Punt Rd. Are other images carelessly captioned?

Can the naked couple and dog on un-vegetated, storm-wracked dunes have been photographed at bayside Sandringham as captioned? More likely, its an ocean beach.

My nit-picking matters because one value—the prime use I would argue—of this book is its pictorial history-making, albeit a ‘time capsule’ containing only two, but very significant years.

For instance, now that Paul Cox is no longer with us, Graham’s insights into the filmmaker’s under-researched photography would be of value. In answer to my queries in an earlier email interview I conducted with Howe he was generously conscientious in his replies, saying of Cox that:

“…he was a transformative figure in my life. His influence extended beyond the classroom, as I had the opportunity to manage his photography studio during his trips to Holland. This responsibility led to exciting assignments, including photographing the entire cast of the Melbourne Ballet Company.”

In Epoch Howe gives mention to Cox’s recommendation of Richard Buckle’s book on Vaslav Nijinsky (published 1971) insisting “You must read this, Graham. You will understand what it is to be truly creative,” and in our interview Howe affirmed that;

“He was right. Nijinsky’s stream-of-consciousness writing provided invaluable insights into the creative process, revealing the intersection of instinct, intuition, and technical skill. This lesson has guided me throughout my career, so much so that my curatorial firm has represented the Nijinsky estate for 25 years.

“Years later, shortly before Cox’s passing, I had the opportunity to express my gratitude to him. We were having dinner with the Nijinsky family in Arizona, and I was able to thank him for that profound insight that had shaped my understanding of creativity and art.

“Cox’s own journey from photographer to filmmaker mirrored the multidisciplinary approach he encouraged in his students. His background in establishing The Photographers Gallery in South Yarra and his subsequent transition to filmmaking demonstrated the fluid nature of artistic expression that he sought to instil in us at Prahran.”

The many nudes, unlike the ‘artistic’ productions of photographers of the previous decade and before, including Gordon De’Lisle‘s for whom Howe assisted and dubbed “the Sam Haskins of Australia”, are radical in being captioned with the names of their subjects, and his approach is innovative.

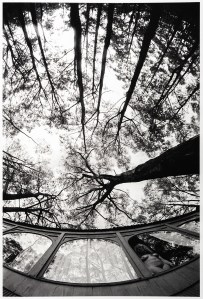

Is there a student of photography who has not taken a wide-angle shot straight up into the trees? Graham’s is an advance on that cliché, a composition in which the environmentalist trope is made a primal vortex, reflected in symmetrical windows, in all but the one behind which ‘Anne’ stands inside, looking out.

However though their bodies become familiar (there are sixteen nudes in the first half of the book) we are left unknowing the individuals and personalities despite Howe’s quite apparent intention to represent them as real people, naked, enjoying a sense of freedom in identifiable, subjectively relevant, or semi-surreal, locations, and without the directed, sometimes preposterous poses that make Paul Cox’s versions often so stilted.

One nude figure, Gillian Flounders, is given her full name, a photo by her, of a man photographing a woman in a park, appears in Graham’s 1974 The new photography that he produced for the ACP, and in which he prints her biography: “Born on September 15, 1951, in London, England. She has studied film and television at Swinburne College of Technology, and has worked for Laurie Thomas commercial and industrial photographer for two years. Her work appears in McMillans Educational Text books. She likes travelling to the bush, reading and being at home.”

Flounders graduated in 1971 from Swinburne with Gillian Armstrong, illustrated Department of Agriculture publications (1977), is listed in McCulloch’s Encyclopedia of Australian art (1984 ed.), and was a contributor alongside David Druce, Ron Eden, Sandy Edwards, Rennie Ellis, to Woman 1975 a YWCA and Dove Communications production for International Women’s Year.

It was feminism’s decade, but you won’t find the word in Graham’s book.

There are other illuminating details that emerged from our ‘virtual’ discussion, however minor, that might have democratised this book, such as the identity of Robert Reid whom Howe remembered to me as a “friend and fellow musical and visual arts creative…whom I had known for five years since our days at the Glen Waverley Camera Club” and who shared their flat, “a converted stable.” He was a colleague of Susan Russell and Mimmo Cozzolini on the student rag, Thigh and posed nude for Howe on several occasions.

Peter Timms makes an appearance, photographed in Shepparton in his motorbike helmet and embracing a pair of cattle dogs in the dust, but it’s useful to know that he, like Graham, was soon to become a curator, assembling important shows for the regional gallery there, then graduating to director. What influence did these ascendant young men have on each other?

The conservatism of Australian society so at odds with the counterculture of Howe’s cohort is made emphatic in several juxtapositions in his book’s layout, and the most powerful sequence is his documentation of the Moratorium to end the War in Vietnam in September 1971. This is not the first Moratorium of May 1970 which 100,00 attended, but the fourth, which also gridlocked the streets of Melbourne.

With the advantage of being a tall man, Howe is able to survey the crowds to produce outstanding imagery as protestors listen intently to the speakers, federal Labor politician Jim Cairns (later Deputy Prime Minister under Gough Whitlam), Jean McLean (leader of Melbourne’s Save Our Sons, ALP member and later, Prahran College Union director); Laurie Carmichael, of the Amalgamated Engineering Union; and student representative Harry Van Moorst.

“Then came our war-not the World War of our parents, but the Vietnam War. Australia’s alliance with the United States brought it close to home. At eighteen, living in Singapore, I filled out my conscription papers, waiting to see if I’d be called for military training.

“But the geography unsettled me. Singapore was just a thousand kilometres from Vietnam, practically neighbors. My life was a mosaic of Chinese, Malay, and Indian cultures; the Vietnamese weren’t distant foes but familiar faces, fellow Southeast Asians. Yes, we lived in a British-dominated enclave, but the idea of going to war against neighbors felt jarringly surreal.

“At eighteen, I was compliant, unquestioning, yet deep down, there was a quiet confusion, a sense that something didn’t add up. What did it mean to fight a war so close to home, a war that seemed both near and impossibly far in its purpose?”

As an autobiography Epoch presents an image of Graham as bold and purposeful in his photography. He ‘knew what he was about,’ as might have been said of him as an Air Force dependent when at 16 his family was posted to Singapore, where he attended the RAF Changi Grammar School for three years and studied for London Board of Education “O” and “A” levels.

” I found a deeper sense of identity and purpose, a glimpse of who I might become.”

Surprising for such a school, it also offered Studio Art. The school’s teachers (“exceptional” in Graham’s estimation) nurtured his artistic talents and “interests that were discouraged in my previous Australian schools.” Coincidentally, both Howe and Bill Henson attended Mount Waverley High School, but five or six years apart.

Details such as on Howe’s relationships with the persons pictured are sparse within the covers of Epoch and though one might regret that as a lost opportunity, especially given Howe’s stature in the photographic world, it is expedient. As Newton emphasises, this is “Graham Howe’s retrospective view of his life as an undergraduate art student at Prahran College, Melbourne, in 1970-1971, presented as an artist’s book.” For this sumptuously-produced photo-book, admittedly, such material would be expensive to include, so one must limit one’s recommendation of it to the high quality of the photographs and their historical value.

Howe confirms that the book is:

“a tribute to that time a reflection of my experiences, the people I met, and the stories that unfolded around me. Each photograph serves as a snapshot of my growth as an artist and an individual. I wanted to share these images not only as a documentation of the past but also as a reminder of the power of observation and the importance of seeing the world through our own unique perspectives.

“I hope readers feel a connection to this era and find inspiration in the raw, unfiltered moments that shaped my life. The 1970s in Melbourne was more than just a phase; it was a defining moment that continues to influence my work today.”

Further intelligence awaits Graham’s more comprehensive autobiography or biography.

Gael Newton has reviewed the book here.

One thought on “Epoch”