Bryan Gracey, whose lectureship at Prahran spanned exactly the decade of the 1970s, was interviewed by Peter Leiss:

At the beginning of 1970 I went along to Prahran with my portfolio, with a view to becoming a student. Gordon De’Lisle was then head of the department. He looked at my folio and said, “Why would you want to become a student?” He said, “You’ve got a lot of skills in photography and colour printing. We need someone with your technical abilities. We can offer you a position here at Prahran”. I honestly couldn’t believe it, and that was how I started at Prahran.

I was born in Ireland and went to school in London then came to Australia when I was 16. My first job here was as an assistant photographer to a newspaper photographer in Yallourn, in the Latrobe Valley which was where I got an interest in photography. I wasn’t particularly interested in it as a kid, but there weren’t a lot of jobs in the Latrobe Valley and that was one I slotted into very easily. That was my start in photography. I left Latrobe Valley and went to Adelaide where I worked as a photographer in a hotel taking photos of clients having dinner in the restaurant at night. You’d take the photo, process the film and return to the client with a 10 x 8 print in a folder, which you would hope to sell.

When I then came back to Melbourne I was working at the Southern Cross Hotel, and one of the clients who was always having dinner there was Athol Shmith and he always tried to have his picture taken [laughs] which I found very flattering.

I think I drifted into photography rather than made any conscious decision to become a photographer. I found taking photographs fairly easy, pretty straightforward. One of my first jobs was doing the catalogue photography 2-3 days a week for McEwans, a forerunner of Bunnings. It all became rather repetitive, so that’s when I decided to apply to Prahran to see if I could expand my horizons a bit.

Around that time I was employed by a company called Latrobe in Latrobe Street, which was probably the biggest commercial photographic studio in Melbourne at the time, and I worked in their colour lab. My main role was processing colour film, both colour negatives and colour transparencies, and getting involved with colour printing, but also in photographing paintings and flat art in the studio.

I started at Prahran in 1970 and was there through to 1980. Initially Gordon De’Lisle was head of department, and Paul Cox and Derrick Lee were there. There were 4 of us teaching.

Prahran was part of an art school and the orientation of the course was very much one of encouraging free expression, in terms of the students. Compared to that, RMIT was very much a technical course. I know that because after I had started at Prahran they said I hadn’t got any formal qualifications, so it would be good if I went to RMIT as a part-time student to complete the Diploma of photography, then later the Degree, which I did. The difference between the courses was extreme; Prahran was very free and very open, whereas RMIT was more concerned about the technical aspects. Funnily enough, my main skill was in the technical area so I enjoyed teaching students who were trying to express themselves, encouraging them in how to actually do it in a reasonably technical manner.

I was twenty-three when I first started at Prahran and I had just been married, and then over the period of the following ten years while I was at Prahran we had five kids, so I had a different perspective on life to a lot of the students who were single and just making their way in the world and trying to express themselves creatively. I found it interesting that a lot of the students were happy to come home to where I lived in Carlton at that time to sit around and have a cup of coffee and a chat. I found that very enjoyable, but at the same time was aware of their much freer existence, where I was very concerned about keeping food on the table and keeping five kids fed. At Prahran there was a not lot of interest in commercial photography. It was more about the students’ desires.

Both Athol and John were ideal people to be in the role that they had—Athol as head of department—because they had years of experience and especially John Cato who was a very active photographer in his own right. His work was mainly black and white, though he did some in colour and he did exhibit; it was great for students to see someone of his caliber and standing exhibiting his work.

Whilst I was at Prahran I also had a small business on the side, which was called Overnight Colourstat Services. Its main function was to service advertising agencies who would produce renderings which they wanted to have copied and blown up overnight. I would leave Prahran, go to the advertising agency, pick up the job, take it back to my studio—which was in Carlton in those days—photograph the artwork, process the negatives, do the prints to the required size and then deliver them to the agency in between 8:00-8:30 in the morning because I had to be at the College at 9:00. So I had this interesting two sides of my life; one was the art side at Prahran; and the other was the commercial imperative to actually do the work and deliver to a short deadline.

Subsequent to leaving Prahran I joined Brian Brandt at CPL and actually the business has continued right through to the current day as an active lab, but we no longer do wet processing; it’s all inkjet printing.

My involvements with John and Paul were very different. With John I used to print a lot of his black and white prints for him, and that continued after I had left Prahran. With Paul, I had not had any experience with cinematography before I went to Prahran, but there was a lot of equipment there and Paul was always working on projects in which he got me involved. So I actually ended up shooting, being cameraman on two of Paul’s early films. One of the first films on which I worked with Paul was Illuminations. The interesting thing was that both Paul and I were very shocked when it ended up getting nominated in the 1976 AFI Awards for Best Cinematography, sponsored by Kodak Australasia (winner that year was Ian Baker for The Devil’s Playground). It was an enjoyable project to work on.

The photography course at Prahran was flexible and progressive and the main advantage for students was the ability to present their work and have it critically analysed by Athol, John Cato or Paul Cox, who all had different opinions on the subjects, the way to approach the subject, and the way to light it. It was a worthwhile exercise for the students.

I can remember one of the exercises which I gave my students in the early days was to actually go out and photograph an object, a building or a tree; something that didn’t move, and to photograph it over the twelve hours of daylight, so they would actually see the way the light influenced and changed the shape of the object over time. Paul was more philosophical in his approach to the students, and he and John both often introduced music into their courses to get the students to think about the impact of other arts on their work.

One of the difficulties in running a photography and cinematography course is the cost of equipment, and other departments did not have the same financial restrictions. It was always a struggle to try and get the best cameras at the right price, especially the movie cameras. When you have fifteen students in the class it was very hard to teach them with one camera. We were very fortunate that we had probably 4 or 5 cameras, so you have three or four of them working at the same time.

Having said that, space-wise we were very lucky in that we mostly had a whole floor in the art and design building in the basement. So we had a reasonable sized studio and one large classroom for lectures and also for discussion where students’ work was put up around the walls and everyone would come in and we’d sit down and we discuss it.

Even after John Cato left Prahran I was still involved with him in terms of printing his work although obviously he wasn’t shooting as much in those days. When John died, both Paul and I were somewhat disappointed that John had never received recognition for his work. The opportunity came up to have an exhibition of his work at the 2013 Ballarat Photo Biennial. We decided to produce a small book which illustrated his work and discussed his life, because John had a fascinating life and he was totally dedicated to conveying his vision of photography and its place in the world.

Among the students who went on to have interesting careers in photography; Phil Quirk had a very successful career based in Sydney. We had Rob Gale, who was a student at Prahran who went up to Hong Kong and worked out of there for a number of years in a very successful career as a commercial photographer shooting annual reports and many other things. Bill Henson has probably got the highest profile of any students, although he only had a very short period at Prahran. I think Bill always knew what he wanted to do and he continues to be a client of CPL to this day; we still process his film even though we don’t print for him any more. Julie Millowick and James McArdle both went on lecture at other colleges. Chris Köller lectured at the Victorian College of the Arts and there are many other students who went on to have very successful careers, too numerous to mention.

I think the merger of the Prahran photography department with the VCA was inevitable because art schools were on the way out and the only successful art school was the Victorian College of the Arts. I think it was the appropriate transition for Prahran and the style of photography in the early years of Prahran College was very different from the style and standard of work that has developed from that point.

The most significant experience in my life was getting married and having five kids. Of the five I have, Cassandra works in the music industry in the UK, very successfully. Michael Gracey, my son is a film director and his first feature film was The Greatest Showman. He’s currently just finishing a feature on Robbie Williams and he was the executive producer on Elton John’s film. Patrick, my other son, is a general manager and producer on the stage, in the theatre, in London. My other two daughters Natasha is a teacher-librarian and Jacinta is a neuropsychologist at a hospital here in Melbourne. But if you speak to my wife, she will say the two girls have got real jobs that have a big influence on people’s lives… so, you know, do people who work in the arts industry, do they have a bigger influence on people’s lives than someone who is having a more regular type of career?… I don’t know, I think that each have their own impacts on people’s lives.

Given the development of artificial intelligence at the moment and the ability to create images from as few as 3 or 4 words that are very hard to pick from something that somebody has gone out, set up, and photographed, so the change between photography now and five years ago has been enormous. And it is going to continue to evolve.

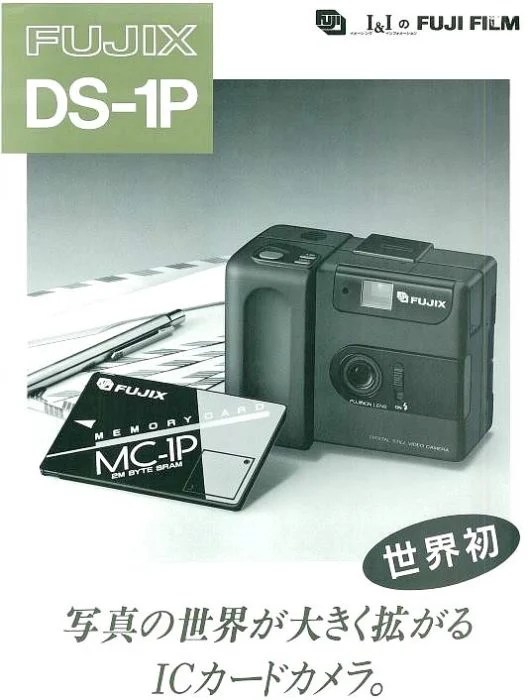

It’s hard to believe that Kodak, which was the single biggest photographic company in the world, failed to fully embrace digital, and subsequently over time slipped further and further behind and eventually went broke. The Japanese supplier of Fuji film managed to have a much greater impact in the photography business than Kodak because they did embrace digital, did produce good cameras themselves and had good people who had worked in the business and encouraged and supported photographers.

One of the main things as a photographer, or in my case as a lab person, is that you have to keep adjusting to the market place in terms of the demands of the clients and also the availability of supplies. Kodak, Fujifilm and Agfa in the early days were big suppliers of photographic materials, especially colour materials, but Agfa exited from the market place and no longer brought supplies into Australia. So you have to keep changing to the demands of the market, the marketplace and availability of materials.

Whether it’s for the better or not is obviously open to interpretation, but I think it’s becoming harder for photographers to make living in the current environment than it was in my early days, you know, ten and 20 years ago. It was very easy to open up and start practising as a photographer and make a living. To try and do it today is so much harder.

6 thoughts on “The Lecturers: Bryan Gracey”