One should not underestimate the contribution of one often unsung class of staff member in an educational institution. Good advice to any beginning teacher, and a valuable recommendation for students too, was that in starting at a school, college or university, the first people to make friends with should be the technicians. Teachers and lecturers may contribute wonderful ideas, but nothing gets done without the technicians.

At Prahran College Andrew (‘Andy’) Lyell was the go-to for fresh chemistry, to borrow a large-format camera or to assist with unfamiliar equipment, until he retired and was replaced by that paragon of patience, Murray White, in 1974.

For alumnus Lynette Zeeng the most valuable lessons she received were from Bryan Gracey‘s teaching and from Andy LyelI in the darkroom; “many of the skills and techniques he showed me became a significant part of my teaching and professional work. Andy Lyell must have taken a shine to me and was very helpful, I guess because I respected the darkroom.”

Julie Millowick who studied at Prahran 1974-6, also remembers the invaluable help given her by Andy Lyell during her initial weeks in the course. She would visit him as he worked in his own personal darkroom sited on the opposite side of the corridor to the teaching darkrooms, where she found him a highly skilled printer. His one-on-one support came at a crucial early time and helped secure Julie’s first job in photography late in her first year at the Shmith-Cato studios, and subsequently in 1986 when printing 40x50cm and 50x60cm archival fibre-based photos of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones from the original negatives of Dezo Hoffman. The latter assignment lasted over 20 years and was secured through skills Andy had taught Julie decades previously.

Andrew Robertson Lyell was born 25 October 1913, the only son of Mary Emma Lyell (1876-1950) standing proudly in the snapshot below. She was notable as the second woman to be president of the Historical Society of Victoria 1935-42. Born at Maryborough, Victoria, she became qualified as an accountant before the Institute of Accountants and Auditors rejected the admission of women in 1912 (a rule they reversed in World War One when the shortage of male accountants meant women had to step in to take their places).

On Christmas Eve 1912, at age 36, Mary became the second wife of the man next to her in the snapshot, Andrew Lyell, whose resemblance to his son is uncanny and, according to his descendants, was, like Andy, a fine photographer as well. He was managing director of Lyell-Owen Pty Ltd, originally located in 239 William Street, on the corner of William Street and Lonsdale Street (now the Magistrate’s Court).

Lyell Snr. was President of the Master Process Engravers’ Association and the sole owner and managing director of Lyell-Owen Pty Ltd., a friend of World War One military commander ‘Pompey’ Elliott and, from 1929-1935, a Hawthorn City Councillor. He was also a devoted Rotarian and once was Master of the Hawthorn Masonic Lodge. He died on July 1948 aged 73, noted by The Argus as “one of the oldest process engravers in Melbourne. His wife Mary died only 2½ years later on 7 November 1950 aged 74. Andrew Lyell senior’s father came from Scotland and moved to Stawell where he was the proprietor of the Pleasant Creek News, beginning a long history of printing and photo engraving in the Australian family.

Andrew junior with his two step-sisters lived in Hawthorn in Fairview Street, not far from the Yarra River and trained for the printing industry in the family business. He married Kathleen and they had their first child, a son, in January 1939, nine months before World War 2 was declared and during which he enlisted in the Survey Corps of both the Citizen Military Forces (CMF) in 1941, and from 1942 in the 2nd AIF (Australian Imperial Force) where he was made Captain. He served only in Australia.

Andrew Lyell jnr. at first worked, before and after the War, in his father’s business as process engraver and Assistant Manager, maintaining a successful and prominent business which garnered praise. In an article ‘From Cradle To Manhood The Story Of Victoria’ in the Literary section of The Age of 17 November 1951 ‘D.J.B.’ reviewed The Story of the Century, 1851-1951 and notes that “Democratic governments are necessarily heavy and slowly-moving vehicles. They are often accused of being unimaginative. This may be so. But let it be said at once that in the field of publishing, or rather in stimulating this art, the present administration [John McDonald’s Country Party] has revealed surprising initiative and vision. Produced in the opulent format of the story of gold discoveries, this latest volume has character. It is packed with facts and photographs and spiced with color [sic].”

The article concludes with the following accolades;

“The Story of the Century is more human than history ordinarily. For this we have to thank the author, Mr. Harold Balfe. Also in a list of high credit must be mentioned Mr. John Alanson for the production, the Specialty Press Ltd. for printing and binding, Department of the Interior for color photography, and A. Hughes and Sons and Lyell-Owen Pty. Ltd. for the engraving.”

Lyell-Owen made plates for numbers of popular Australian histories including the deluxe hardcover, Land of the Southern Cross: Australia by Bryce Kinnear and the Australian Publicity Council and further assisted in publishing Victorian history in its provision without charge of production of plates for There goes a man; the biography of Sir Stanley G. Savige (the army officer and founder of Legacy) by William B. Russell, published by Longmans, UK in 1959.

In 1963 the partnership was dissolved and the business moved to a converted building at 101-107 Rosslyn Street, West Melbourne constructed for the large company of partners Alfred Felton (his Felton Bequest benefitted the NGV) and Russell Grimwade (he who brought Captain Cooks Cottage to Melbourne). Before once again it was converted, this time for apartments, it was Creffield’s digital design and printing firm who next occupied the building. That was ironic, given how computer-to-plate (CTP) technologies had dispensed with human-controlled steps in photomechanical process engraving for plate-making in which the Lyell-Owen business had triumphed.

Process engraving during the 1920s-1940s was a labour-intensive and highly skilled profession, requiring expertise in both artistic interpretation and technical processes to produce the imagery in newspapers, magazines, posters, and advertisements; materials of the visual culture of the time. The proliferation of mass media advertising, and quality publications at the other end of the scale, caused the competitive industry to undergo significant development and refinement.

Process engravers worked through several intricate steps and specialised techniques. To prepare original hand-drawn illustrations, paintings, or photographs for photoengraving often involved touching-up or adjustments to enhance clarity and contrast. The half-tone process operator poured collodion over one surface of glass plate, and placed it in a bath of silver nitrate for sensitising, then the plate, in wet condition in a dark slide, was taken to the camera for exposure by the photo-operator. For halftone work the operator first focussed and adjusted the position of a crossline screen. For line work no screen was used. After exposure they would develop and fix it, intensifying, if necessary, by immersion in a copper or silver solution or lead nitrate. Colour images required four separate plates to be exposed, processed and printed in exact registration. Plates were then acid-etched by operators with specialist skills. Proofs were made to check for accuracy, clarity, and colour fidelity and adjustments or corrections would be made on the plates before the final relief, lithograph or intaglio gravure was printed.

Janet Russell, Andy Lyell’s daughter, points to the way that artistry, attention to detail and care demanded in the printing industry honed his skills as a photographer and photographic printer. She found him patient in teaching her how to print. After studying at RMIT from 1968, Russell continued with a lifelong career in photography including at Latrobe Studios in the B&W department, and printed for Ian McKenzie, the earliest appointment in the Prahran College photography department. She says she met her husband through Andy when he answered the phone to Dennis Russell who was looking for a printer.

Presumably it was in 1963, after the dissolution of the family business that Lyell Jnr. set out on a new career as a photographer.

Presumably it was in 1963, after the dissolution of the family business that Lyell Jnr. set out on a new career as a photographer.

Some of his work was for architects, and what little of that remains is preserved in copies of CROSS-SECTION: A Private Communication to Architects and Master Builders a newsletter printed with good quality illustrations by the Department of Architecture at the University of Melbourne from November 1952 until February-March 1971.

The Cross-Section Collection, a valuable entrée into the history of mid-twentieth century architecture in Australia, includes more than 4,000 photographs and numerous negatives sent in to the editors by architects, builders and designers from across Australia. One set of images is of unnamed commercial offices including photographs taken during their construction in Victoria, New South Wales and Western Australian in the 1950s and 1960s and published in Cross-Section between 1956 and 1971. In an index to this collection—which names important architects including Ernest Fooks and Harry Seidler—Andrew R. Lyell is singled out as a “notable photographer.”

Andrew R. Lyell’s photographs appear amongst the Melbourne Architecture Faculty holdings of 75 black-and-white prints of flats and apartments in Australia of the 1950s-1960s alongside those by Helmut Newton, Wolfgang Sievers, Max Dupain, Mark Strizic David Moore and Ian B. McKenzie. That raises the question of whether it was McKenzie who hired Lyell for the position of technician, having perhaps worked with him on such jobs, however Ian Macrae, who started amongst the first cohort taking the Diploma in photography, does not remember him, and Lyell appears in neither John Cato’s history of the department nor in Judith Buckrich’s Design for Living: A story of ‘Prahran Tech’. No student seems to have photographed him. He has indeed been unfortunately overlooked in histories.

Lyell was sixty-one years old in 1974 when I encountered him, and on the verge of retirement, which then was 65. He was installed in a narrow darkroom/office next to Bedric (‘Fred’) Valis’ printmaking studio, and across the corridor from the photography classroom A4 in which our assessments were held. He is given credit as technician in this catalogue for an exhibition at the AMP Building of Prahran photography students from all years;

When few people were around Andy would mix up chemistry for the students’ darkroom and the deep tanks in the film processing booths, which were tucked beside a narrow passage which reeked of chemistry, pipe and cigarette smoke, leading to Athol’s office and to the colour film processing UniLab darkroom.

First thing Monday morning he’d make a lethal cocktail of fixer by just pouring the hypo crystals straight into the trays filled with hot water—contact with your prints would bleach them a negative version of chicken pox! No wonder that Andrew Chapman remembers “asking him (as a raw first-year student) if any of the chemistry could harm you. He thought a bit about it and replied, ‘if you drink too much hypo, it’ll probably give you the shits!’”

I knocked on his door once and asked him to top up the dev. and found him printing on a massive floor-mounted Durst Laborator 138, and there discovered, pinned to the walls, his prints of steam trains, which he had been photographing and publishing since at least the 1940s. It was a revelation, since no-one had mentioned this of our technician. It is rare for commercial photographers to pursue a personal passion for the medium in their own time after employing their talents to clients’ demands. Andy was one of the few and his family were witness to his dedication when they accompanied him on his constant quest for the perfect train photograph.

There is a long tradition of railways photography published for a strong following of mostly male enthusiasts that relates closely to the rather English hobby of trainspotting which was at its peak between the wars.

After WW2, a fresh form of the trainspotter subculture viewed their quarry through a lens of nostalgia, romanticising it as a reflection of a cherished era in British history. During Lyell’s youth of course, Australian popular culture was contiguous with the British.

His pictures, about 5,000 of which may be found in the Buckland collection of 25,000 railway transport photographs in the National Library of Australia, while an invaluable, technically excellent archive of the days when steam was the primary means of moving freight and passengers around this country, they may not equate to the virtuoso night performances of the American O. Winston Link, nor do they sweep us up in such energy as is found in the Swiss, René Groebli’s classic book Magie der Schiene (‘The Magic of Steam’). They are picturesque, in that they ‘make a picture’ of the subject in imitation of a picture already seen and admired, and are thus a species of Pictorialism unrelated to the Modernist machine-worship we see in the commercial work of Max Dupain. His image of the Ghan’s then contemporary and thus less glamorous diesel engine is made at a more objective distance but evokes, with the nicely placed framing of a Eucalyptus papuana, the outback landscapes of the classic Australian Pictorialist Harold Cazneaux.

Lyell was fastidious and strategically photographed different engines from an habitual advantageous viewpoint to produce almost identical images, by which means he refined his composition.

Nevertheless, Lyell’s infatuation with steam trains is not mere trainspotting. The Light Railway Research Society of Australia in its Light Railway News of April 1978, after his death on 8 January that year aged 64, remembered him as a contributor to Light Railways who was:

“an authority specialising in the history of early mining railways and tramways of Victoria, besides being an outstanding photographer and patient researcher…he was also a long-time member of the Victorian Model Railway Society. In that capacity, he participated enthusiastically in helping to create detailed working models of historic V.R. locomotives and rolling stock to operate on the elaborate model railway built by V.M.R.S. members in association with the V.R., which was one of the outstanding exhibits during the Railway Centenary Celebrations in September 1954. In this project he was aided and abetted by his wife, who became equally skilled as a model-maker.”

A technical photographer, he was employed in an art school in which lecturer Paul Cox was treating the medium as an artform. His own imagery of steam trains evinces a brand of industrial romanticism, though one in particular stands out as poignant. It is a scene with no locomotive, like a portrait without a sitter, representing the decay of the rail system that once spread its steely veins and countless capillaries across the state of Victoria.

After his retirement, or perhaps precipitating it, Lyell fell ill. His former Head of Department Athol Shmith sent a fulsome letter of appreciation in sympathy and hopes for a fast recovery.

Athol’s letter reads:

“Dear Andy, I was most distressed to learn of your recent bout of ill heath, and trust, as this year is ending, that 1978 will bring you all health and happiness. I have always appreciated your kindress and assistance during our association at Prahran — mostly beyond the call of duty. I cannot recall any occasion when your expert knowledge was not available to myself and the students. Apart from being a help mate I have always valued your friendship — a situation I hope shall continue in the future. Many have asked me to pass on their best wishes for a speedy recovery. John Collins and others from the National Trust may have already written. When you feel better they would appreciate your assistance in preparing a publication including your shots of vintage trains and bridges—particularly on the old Bendigo to Melbourne line. If I can be of help in this direction, please do not hesitate to let me know. Look after yourself dear Andy for we do miss and need you. With warmest love, Athol”

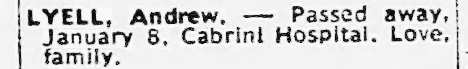

Regrettably Athol’s wishes for his former technician’s return to health were not to be. Too soon, this death notice appeared in The Age:

It was followed by another on 10 January 1978. Clearly he was remembered fondly at his former workplace:

[NOTE: These biographies are a work-in-progress for which primary research is preferred, but since not all the subjects are living or contactable, they may rely on a range of secondary or tertiary references. If you are, or if you know the subject, please get in touch. We welcome corrections, suggestions, or additional pertinent information in the comment box below or by contacting us at links here]

4 thoughts on “The Technicians: Andy Lyell”