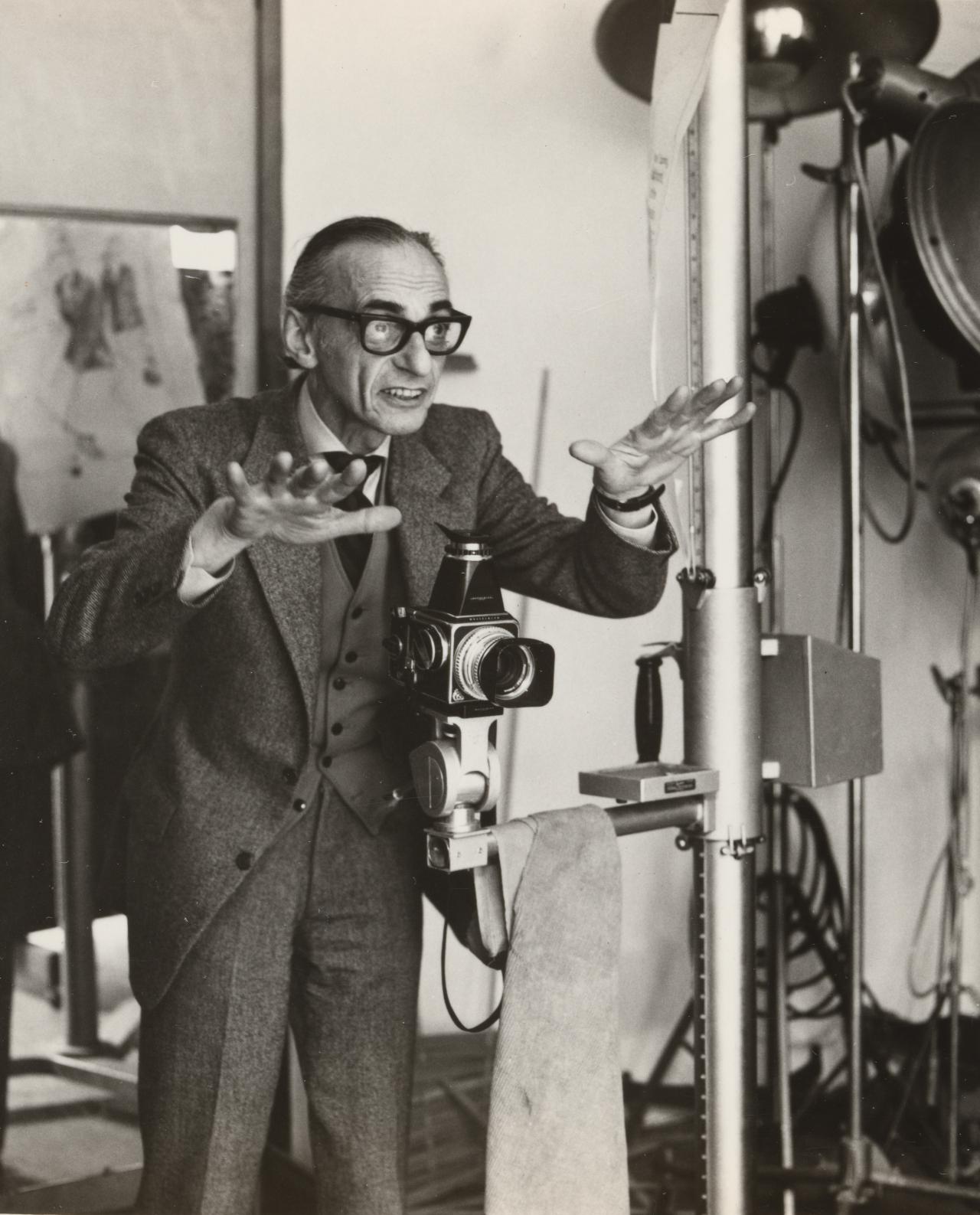

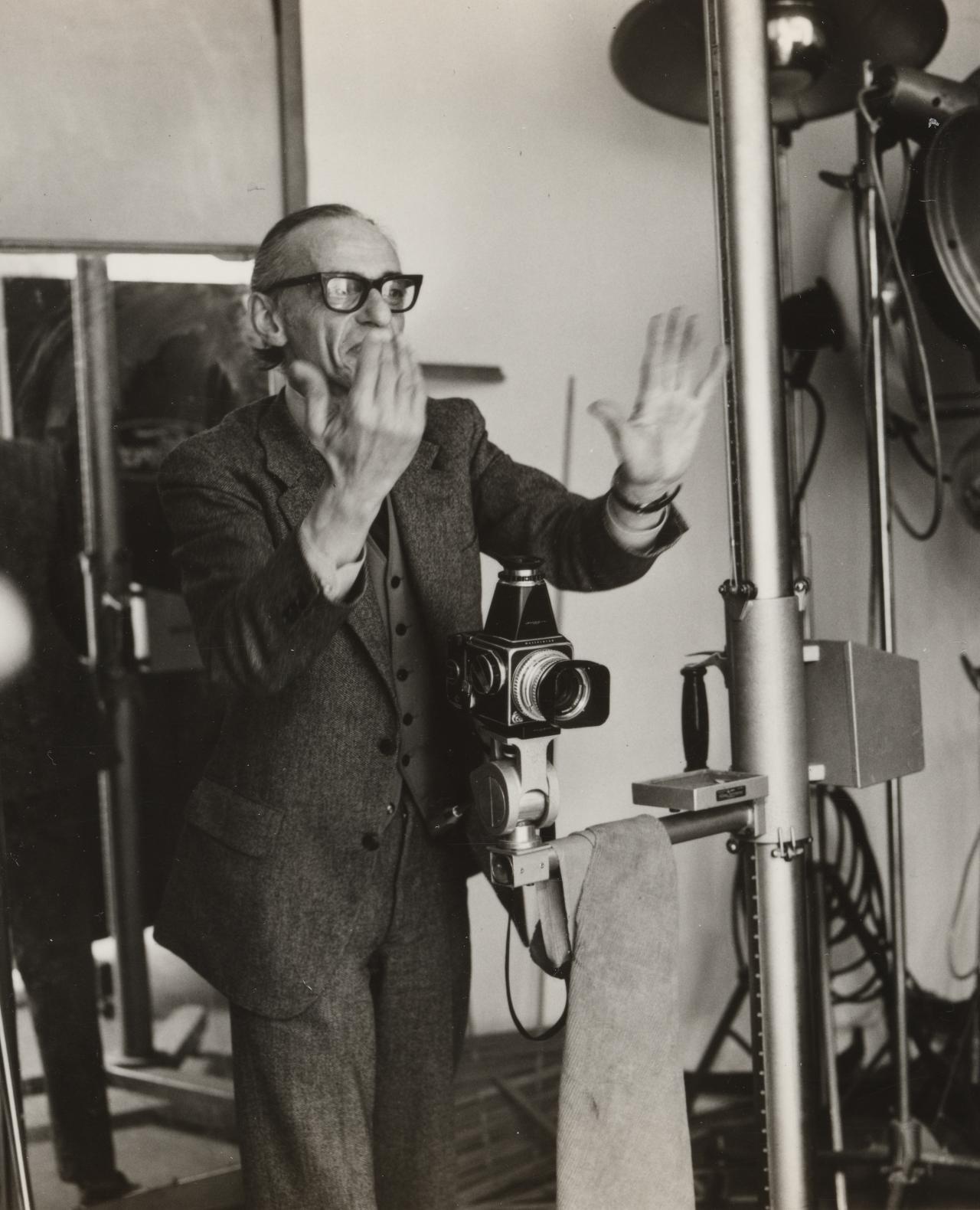

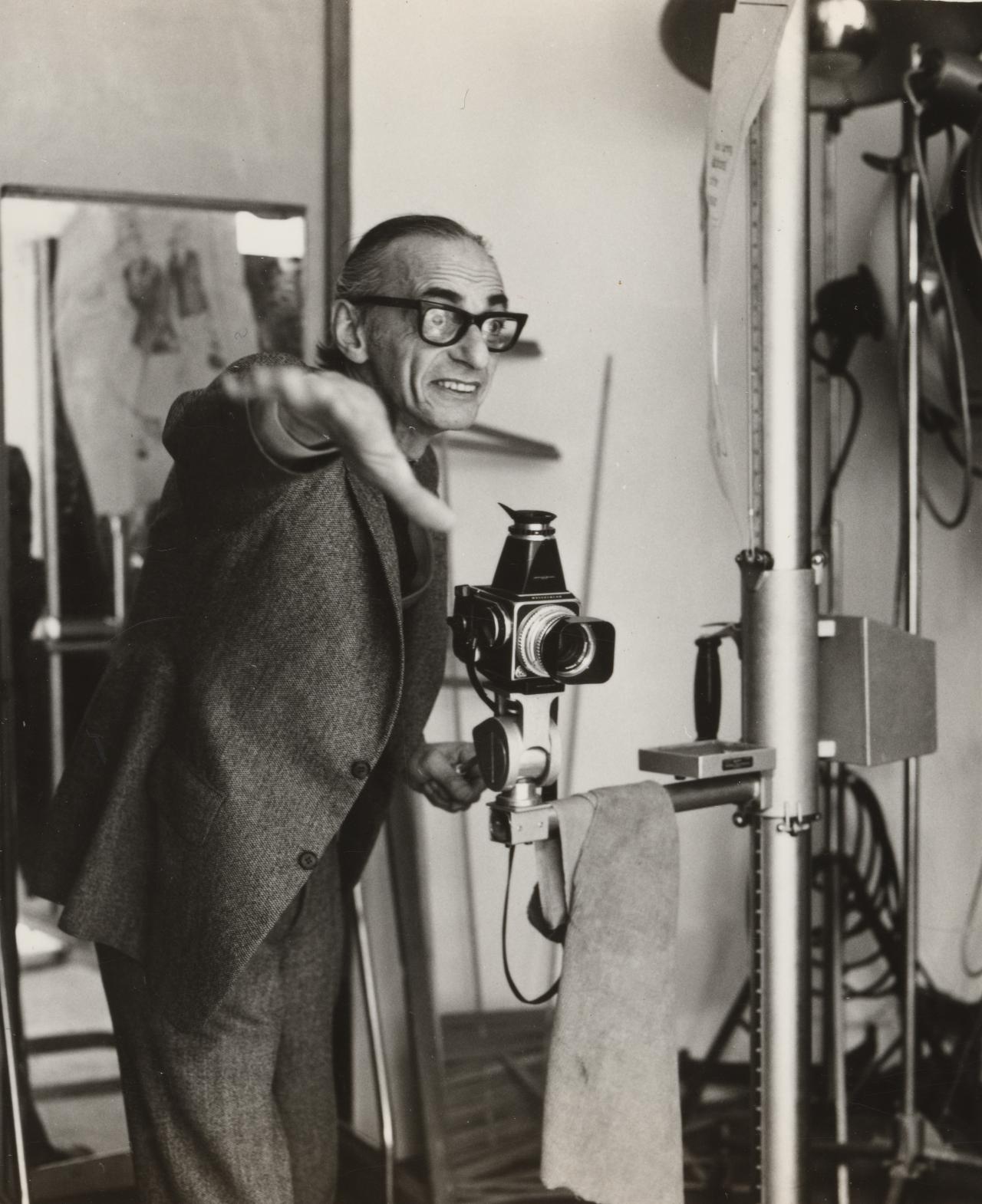

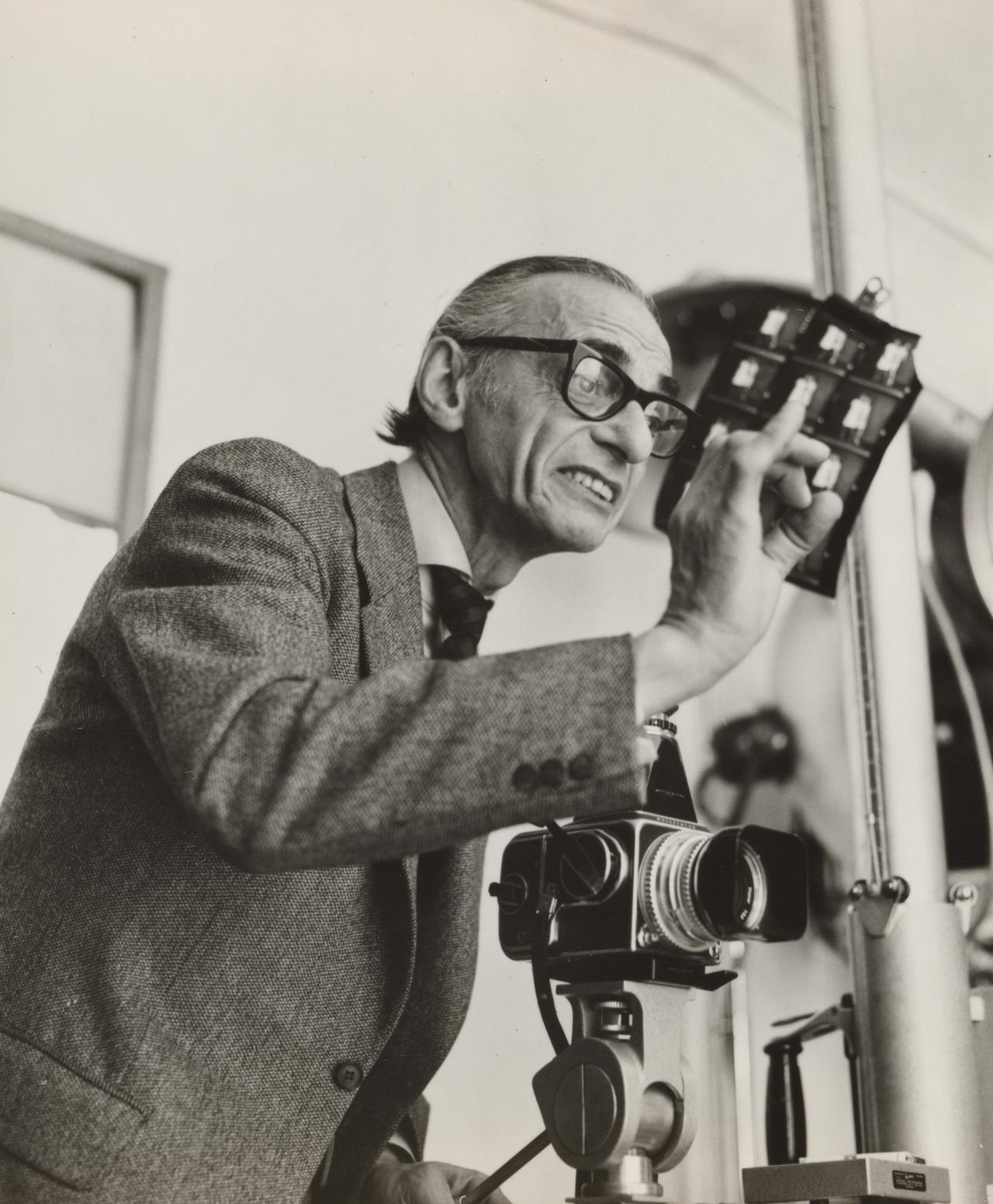

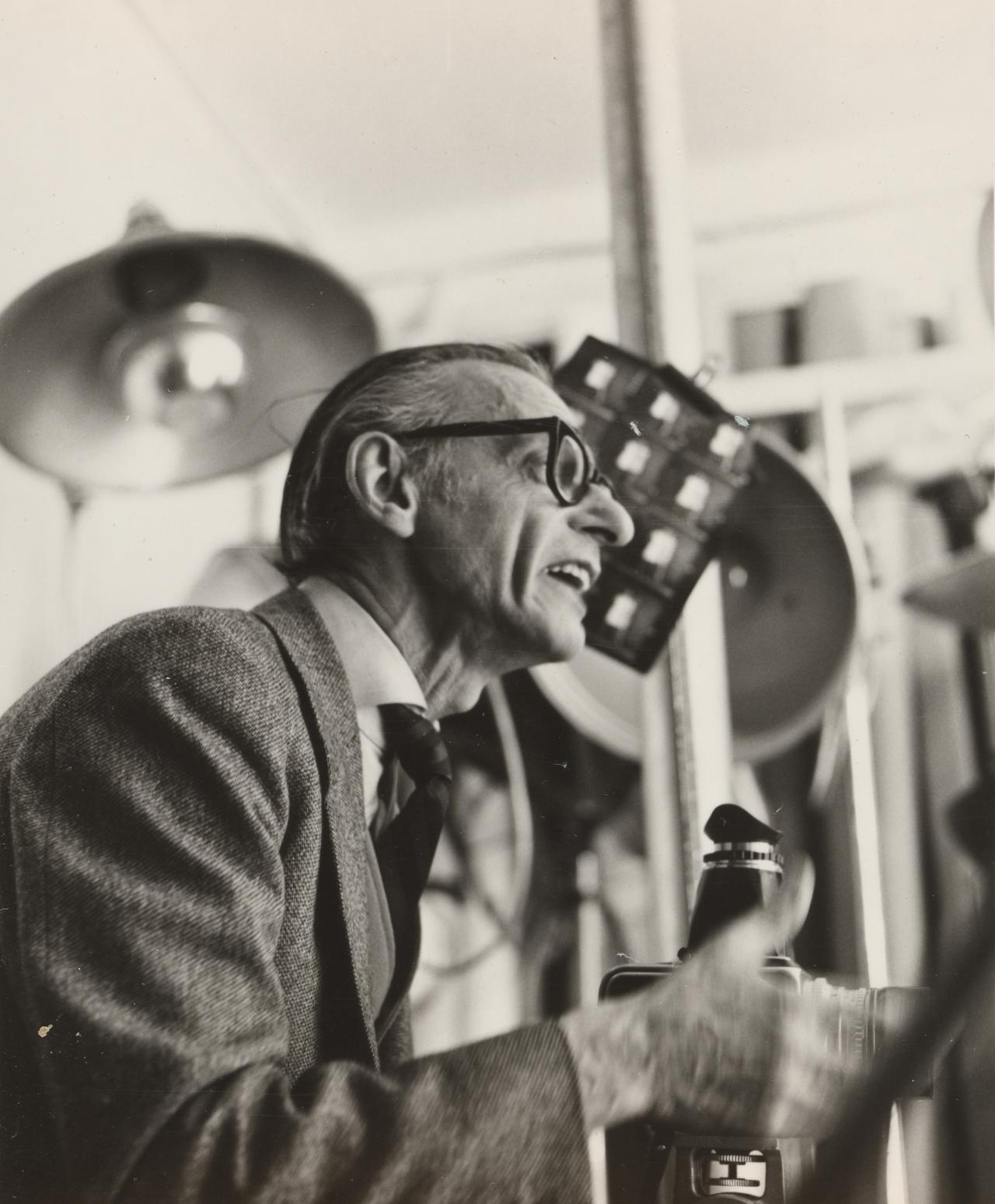

Featured image: Rod McNicol (1978) Athol Shmith, gelatin silver photograph

I was lucky enough to be a student of Athol Shmith F.R.P.S., at Prahran College in Melbourne, Australia, and graduated with their Diploma of Art and Design nearly fifty years ago, so forgive me if this post involves a bit of reminiscence and is an undisguised paean to someone who was a great influence in my life.

I’d belatedly discovered that university Art History would keep me away from my first love, photography; they never deigned to mention the medium in my undergraduate course at Melbourne Uni…it wasn’t considered worthy as an art form in the late 1960s in Australia. So I dropped out and found myself in the dingy, malodorous basement of the Prahran College of Advanced Education.

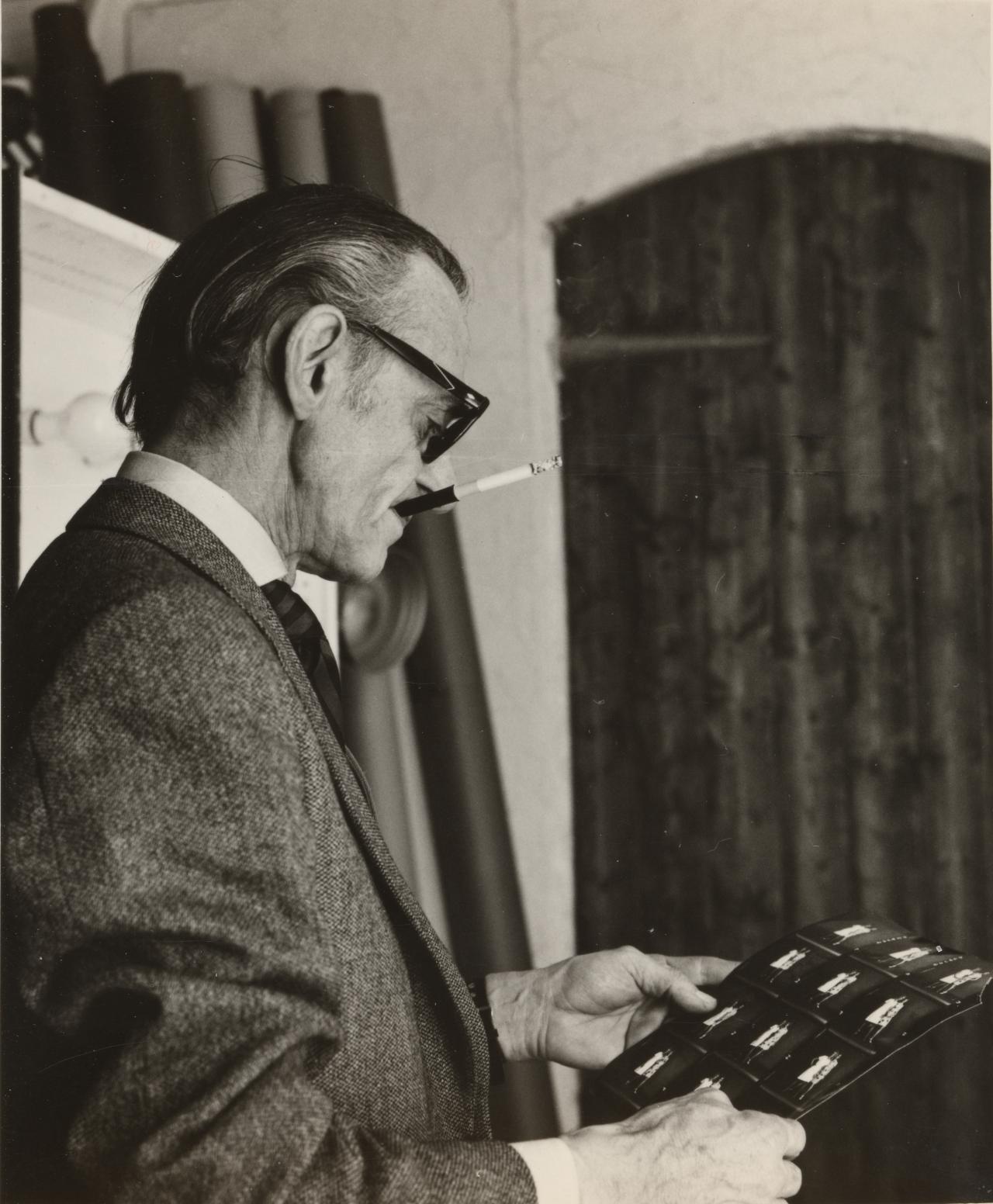

Standing before a beanstalk of a man, I presented my entrance folio, some days after the closing date, apparently. He muttered something about remembering my late father and consented to consider my entry, even though ‘we’re full up’. In the summer heat, my flush-mounted full-frame 16×20 prints were curling from their cheap strawboard mounts in protest at my crappy spray adhesive, while Athol, in a cloud of cigarette smoke, scrutinised them at an uncomfortable range. He called in John Cato. I vaguely remember they asked me a few questions, then told me to take a walk.

When I returned, they were sitting in Athol’s little office deep in conversation and seemed to have forgotten me. Hesitantly, I knocked on the door; “Oh, McArdle,” said Athol…a dramatic pause followed…”You’re in. I think you could edit your folio more thoroughly. We’ll help you with that.” He turned back to John, while I stood there blushing and beaming foolishly. John asked to be remembered to my mother in indication that it was time for me to go. I was stunned…I had now idea that they’d know my parents! So I collected my prints, leaving with the nagging feeling that maybe I’d only got in because of a personal connection..was this nepotism? But I was in. Later I’d find out that the photography world in Melbourne was tiny, that everyone knew everyone, and that other students too had a familial connection with someone in photography.

Athol was a native of Melbourne, son of Genetta, née Epstein, and manufacturing chemist, Harry Wolf Shmith, both from England. He grew up not far from our little College in St Kilda, started photographing at fourteen with he Ansco that his father had gifted him, then at a young age abandoned his music and joined a studio. Just before the advent of WW2 he’d graduated to his own, in the tree-lined Collins Street in the graciously named Rue de la Paix building at 125. It was across the road from the office in which my father Brian McArdle (1920-1969) had edited Walkabout travel magazine through the 1960s, in the Coates building, then the only glass high-rise threatening the renowned Parisian atmosphere of the surrounding Victoriana. In the 1980s those gems were reduced to mere decorative facades for towering skyscrapers, or worse, swept away altogether. The best thing you can read about this era, and about Athol, is this truly inspired piece of journalism by Athol’s son Michael, who also wrote the entry in the ADB.

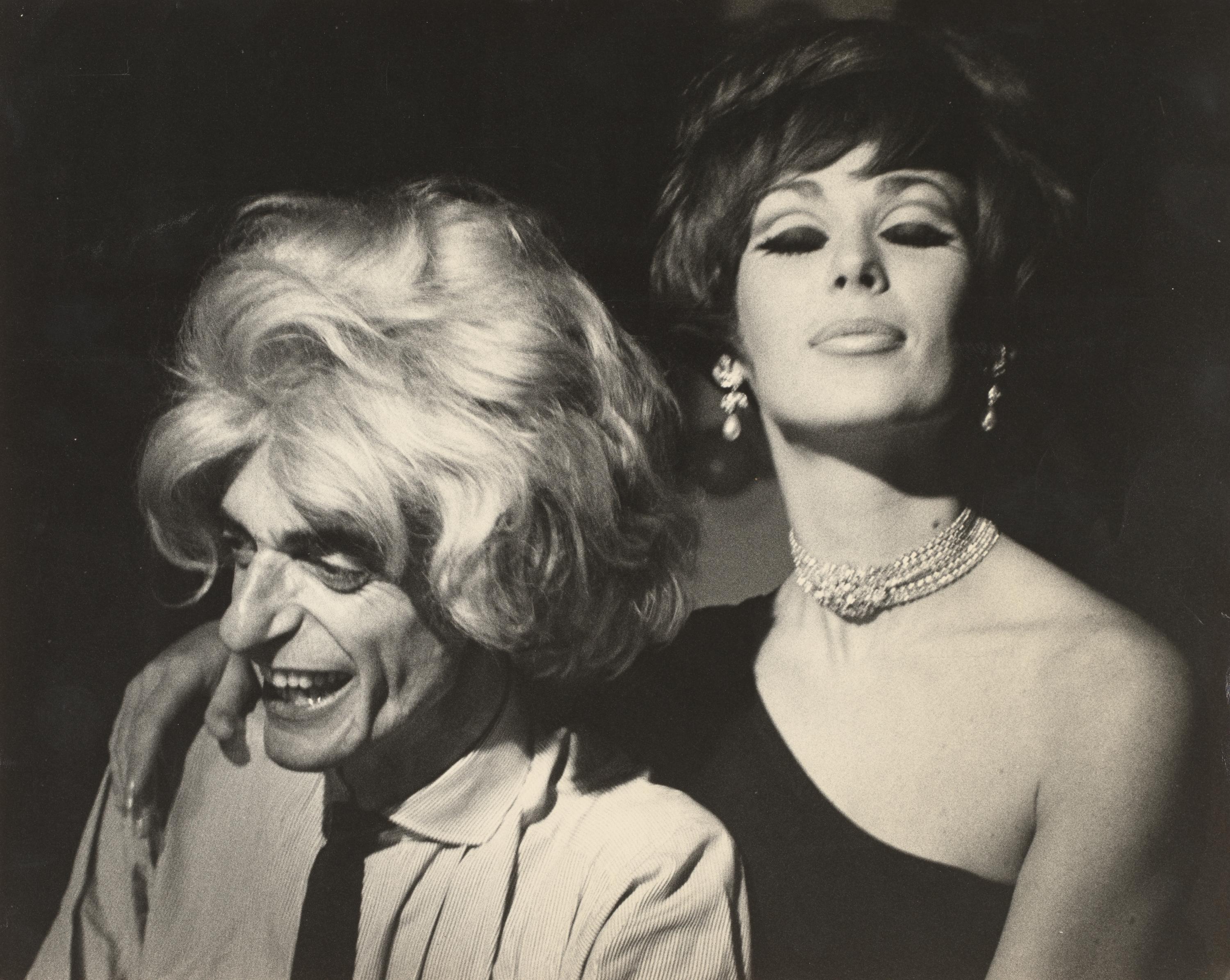

There he was at close quarters to The Oriental cafe, first to serve patrons at tables on the pavement (lending credence to the term ‘The Paris End’ to describe this stretch of Collins St.) and to other photographers of the 1940s-1970s; Helmut Newton, Jack Cato, Wolfgang Sievers and Mark Strizic, with a Bohemian touch added when Georges Mora and artist wife Mirka lived at number 9, the Grosvenor Chambers, and opened their Mirka Cafe, 183 Exhibition Street. Later joined by business partner John Cato (Jack’s son), Athol photographed the lissome fashion models of the era (three of whom he married) and celebrities including Noel Coward, Vivien Lee, Robert Helpman, Laurel Martyn, Prince William, Yehudi Menuhin, Isaac Stern, Sir Dallas and Dame Mabel Brooks, artist Sir Daryl Lindsay, and many more, but many a soldier, including my father, was photographed by him before they went off to New Guinea or elsewhere in the Empire to fight. Cato pursued the more commercial work promoting cars, furniture and factories.

After so many years in the studio, Athol knew lighting; “A photographer’s tool is light.” he would say to his class (“…and heavy is his heart!” unkindly whispered some wag behind the great man’s back). We were held spellbound by the jargon he spouted around portraiture; there was no doubt that here we were getting the full bottle, we’d entered the mystique of real photography: about ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ light, ‘key’, ‘fill’, ‘bounce’ and ‘back’ lighting, reflectors, background washes ingeniously textured with a handy tree branch or cardboard cutout, ‘inky-dinky’ hair lights on teetering booms,  scoops, floods and spots, cheesecloth and vellum diffusers, ‘cutters’, and ‘hatchet’ shadows for manly noses and jaws and ‘butterfly’ lighting to lift the cheekbones of female subjects. “Light for the shadows” he would say, then wheel in a six-foot high Brownbuilt steel cabinet crammed with a multitudinous array of 500 watt floods, threaten all of Prahran with a blackout by switching it on, then hang a smouldering sheet in front of it to show us how to banish shadows altogether (“just the thing to show off the garment fabric in a fashion shot”). The College studio was a maze of ancient lights on well seasoned stands, most of which had come from his own studio, and they were ours to use! I was soon on my way to my first big commission; using my newly learned lighting skills in my illustrations for Anne von Bertouch’s book on sculptor Guy Boyd.

scoops, floods and spots, cheesecloth and vellum diffusers, ‘cutters’, and ‘hatchet’ shadows for manly noses and jaws and ‘butterfly’ lighting to lift the cheekbones of female subjects. “Light for the shadows” he would say, then wheel in a six-foot high Brownbuilt steel cabinet crammed with a multitudinous array of 500 watt floods, threaten all of Prahran with a blackout by switching it on, then hang a smouldering sheet in front of it to show us how to banish shadows altogether (“just the thing to show off the garment fabric in a fashion shot”). The College studio was a maze of ancient lights on well seasoned stands, most of which had come from his own studio, and they were ours to use! I was soon on my way to my first big commission; using my newly learned lighting skills in my illustrations for Anne von Bertouch’s book on sculptor Guy Boyd.

But it was not all just lighting. Athol was a genius at directing models. Urbane, sophisticated and witty, he was by no means handsome, but always impeccably dressed, even when lecturing, in brass-buttoned navy-blue reefer jacket, red waistcoat and Windsor knotted tie—always—while the male students sitting around him (and a couple of his fellow lecturers too) wore flared jeans, beards, long hair and sandals or bare feet. But his mesmerising pop eyes, conspicuous nose and gangly limbs he put to good use. Verbal directions would only interrupt the stream of banter that he used to calm nervous sitters, so after saying perhaps, “Head to the light, now eyes to camera” as if directing a movie star on set, he instead used mime and subtle hand signals; the subject would barely be conscious that they had lifted their chin, shifted their weight, or relaxed their shoulders just the way he wanted them to, they just did it, prompted by his own gestures that they then imitated.

But it was not all just lighting. Athol was a genius at directing models. Urbane, sophisticated and witty, he was by no means handsome, but always impeccably dressed, even when lecturing, in brass-buttoned navy-blue reefer jacket, red waistcoat and Windsor knotted tie—always—while the male students sitting around him (and a couple of his fellow lecturers too) wore flared jeans, beards, long hair and sandals or bare feet. But his mesmerising pop eyes, conspicuous nose and gangly limbs he put to good use. Verbal directions would only interrupt the stream of banter that he used to calm nervous sitters, so after saying perhaps, “Head to the light, now eyes to camera” as if directing a movie star on set, he instead used mime and subtle hand signals; the subject would barely be conscious that they had lifted their chin, shifted their weight, or relaxed their shoulders just the way he wanted them to, they just did it, prompted by his own gestures that they then imitated.

We came to understand that photography was not merely about the camera, but how we interacted with our subjects. To Athol, his Hasselblad was an extension of his long limbs, like his ever-present cigarette holder, his fingers manipulating the camera’s controls like a prestidigitator’s though he appeared to pay it no attention, instead beaming all of his spider-like concentration onto the sitter.

Once he demonstrated his method; “Freeze!” he said in a commanding tone, walking into the classroom one day, “Don’t move. Now look around you at your classmates…what do you see? No-one is sitting in the same pose! We come with our own personal pose; use that fact when you photograph people. Just look at them before you start ordering them around and you’ll know straight away how to photograph anyone!”

Athol’s assignments challenged us to put such skills to use with our humble Pentaxes and Minoltas. We were pushed well out of our comfort zone and into “The Greek Community”, or required, with no prior warning (there was no such thing as a ‘syllabus’), to photograph “A Day at the Races”, or “Anzac Day” (for those of us who had dodged the draft and had marched against Vietnam, this was conscience-altering), or we’d be sent to the Ballet School. There, my classmate Bill Henson produced a series of head shots that became an exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria held, thanks to encouragement by Athol, when he was at the tender age of eighteen.

Most of us experienced such moments of insight and transformation, though without the instant fame, during an Athol assignment, or during the gruelling process of assessment. At these regular sessions, everyone in the class was required to be present, and to speak up, to make some judgement about fellow students’ work alongside sometimes three lecturers’ inquisitions.

His lit cigarette in its holder hovering dangerously close to our precious prints, Athol would scrutinise every offering before starting over to deliver his judgement. There were often tears and some stormy exits, but we learned to see our own work through others’ eyes, to divest ourselves of prima donna egocentrism and to find a voice in speaking about images.

When I graduated to become a freelance photographer and art teacher, it was the memory of these assignments and this assessment method that I took with me.

However, I regret they have no place in contemporary educational institutions with their online teaching, quality assurance, OH&S, student feedback, rigid curricula, and no room for teacher innovation or on-the-fly individualisation prompted by the particular momentary students’ needs in one’s classes.

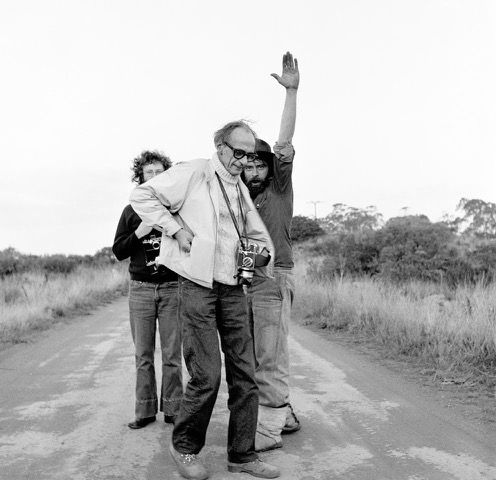

Furthermore, Athol was not one to stand in an Ivory Tower. His interactions with his class included inviting the whole lot back to his home in South Yarra, where we admired his art collection that included exquisite original portrait drawings by Ingres, and after his divorce, we partied at his tiny new apartment. We might regard Athol with reverence, but he would soon show he loved to have fun, to act the fool. Mimmo Cozzolino recorded this incident when Athol took the class to the Red Tulip Chocolate factory just down the road from Prahran, which often sweetly perfumed the neighbouring streets of the College:

“As soon as the factory minder told us we had to wear hats for OH&S and gave us some, Athol said he was going to be Napoleon for a day, turning his into a bicorne, and even wore it in his car for the trip back to college. The shots I took of the factory production line were dismal but I don’t mind the couple I took of Athol.”

He might dress as if for the opera, but was utterly without pretension and when the biscuits ran out, he resorted to buttering his tie with paté and licking it off, to lighten the mood at an exhibition opening.

By a process of osmosis, we came to love photography as he did. He spoke of the medium using the terminology of the musician he was in a past life, and of the lover of esoteric ‘Maaahler’ recordings that he had become

Athol’s selection of his associate lecturers was inspired. There was his business partner John, whose father had written the first (and at the time, the sole) history of photography in Australia, and whom Athol seconded from managing the Collins Street studio that was still in operation.

John had met in person many of the greats through his father Jack, and helped edit his book The Story of the Camera in Australia. At a time when histories of Australian photography could be counted on one hand, he was the resident historian of our medium with intimate, uniquely Australian, knowledge of his subject.

Paul Cox was the earliest remaining appointment for the department recruited in 1968 by Lenton Parr, after having established ‘The Photographers Gallery’ in South Yarra. He was a Dutch beatnik and occult filmmaker, changelessly dressed in sagging black corduroy jacket and slacks that reeked of pipe tobacco, and sandals whatever the weather.

Teaching colour processes was Bryan Gracey whose statuesque figure and Michelangelesque features belied the fact that he was barely older than his students, who in those days were mostly in their early twenties. He and Derrick Lee urged us to digest Micheal Langford’s technical volumes on Basic and Advanced Photography. Lee, appointed by previous head Gordon De’Lisle in 1969, had his training in the UK Midlands and besides lecturing, moonlighted as a children’s magician. He conjured all sorts of tricks from the chemistry of toners and stains, unravelled the complexities of the infant medium of video, and showed us how to ‘paint’ the corridor with light.

These were halcyon days! Thank you Athol, from the bottom of my heart!

[This is largely a repost from James McArdle’s On This Date In Photography of 21 October 2016, on Athol’s birthday]

[NOTE: These biographies are a work-in-progress for which primary research is preferred, but since not all the subjects are living or contactable, they may rely on a range of secondary or tertiary references. If you are the subject, please get in touch. We welcome corrections, suggestions, or additional pertinent information in the comment box below or by contacting us at links here]

A true gentleman

LikeLike