This is the presentation given at Castlemaine Art Museum by one of the Prahran Legacy team, James McArdle on Sunday, 16 June 2024:

Today, photography is dead.

I started Photoshop, opened a blank file and typed in my instruction “Create a B&W photograph of a group of 1970s Australian students making a film.”

The result is, at a glance, plausible, though closer examination reveals that AI is as coy about hands as a first year drawing student; the tripod is a Möbius object; the camera seems set up to run on a two-stroke motor; a drought has consumed the nature strip and something is awry with perspective. Were all students in the 1970s men?

No, not dead quite yet…

You can see I’m channelling Paul Delaroche and his oft quoted claim: “La peinture est morte, à dater de ce jour!” (From today painting is dead!) purportedly made on first sighting a daguerreotype. His utterance was repeated just this morning by Emma Beddington in the Guardian saying that is how “Delaroche greeted, horrified, one of the earliest photographs.”

A history painter, his works were famous for their verisimilitude and smoothness of facture that one might now say was “photographic.” It was due to his celebrity that François Arago called Delaroche to provide a report on the daguerreotype for its announcement at the 19 August 1839 meeting of the Académie des Sciences and Académie des beaux-arts. So his famous dictum is an improbable fiction, hot air in fact, invented 18 years after Delaroche’s own death, by balloonist Gaston Tissandier, himself born in 1843, well after the announcement of the daguerreotype, for his Les merveilles de la photographie Hachette et Cie, 1874. In fact, Arago quoted Delaroche as reporting that the ‘unimaginable precision of detail’ and ‘the nicety of form’ of the daguerreotype would ‘aid the education of painters by providing unequalled studies of the distribution of light and concluding that ‘

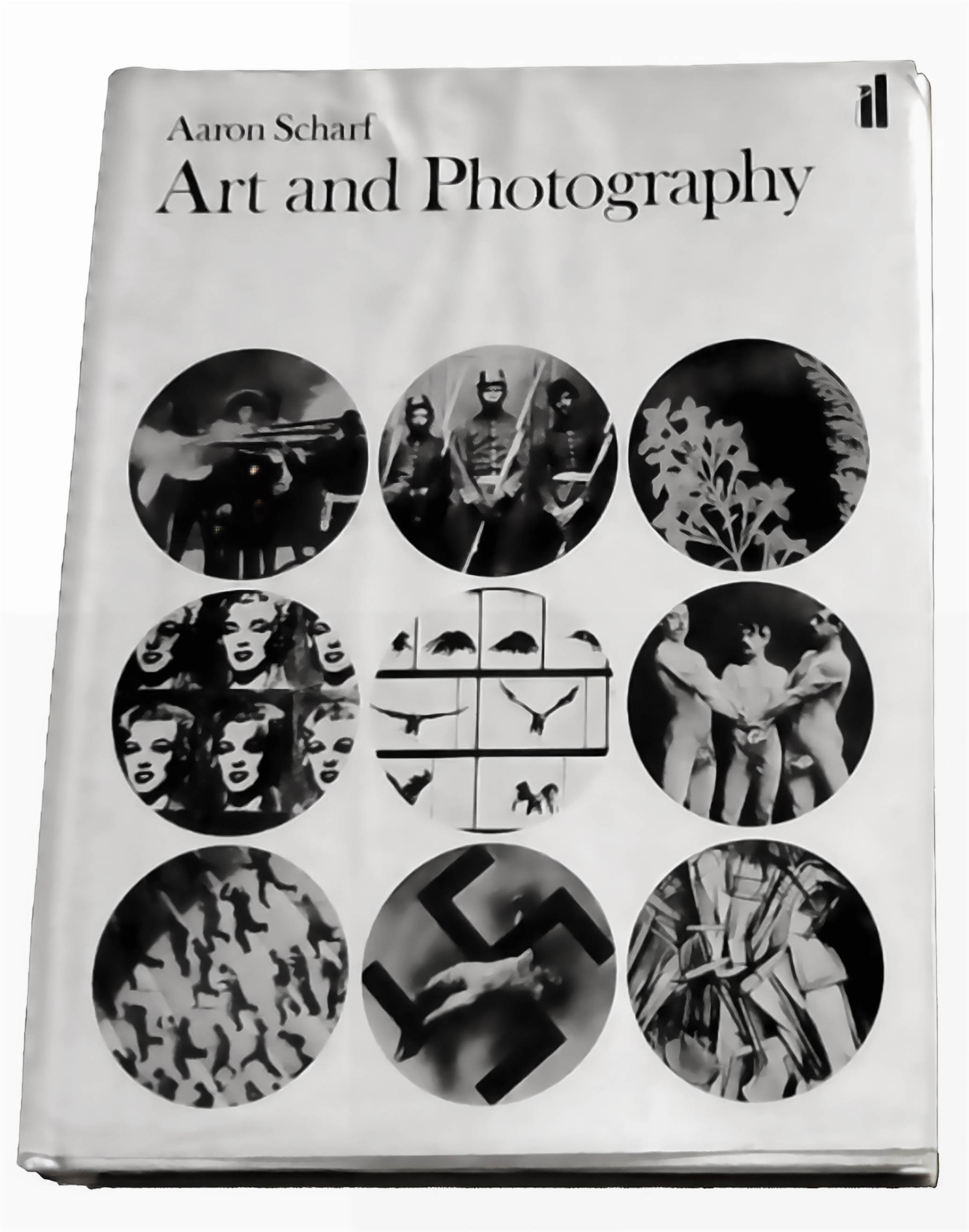

If we are to understand the development and acceptance of photography as art it is useful to survey the uses of photography since its invention. Hundreds of artists who did so were explored over five years of seminal doctoral research at the Courtauld by Aaron Scharf and published in his 1968 book Art and Photography, which was my first purchase of an art book as a teenager.

In that book Scharf shows how America’s Photo-Secession in its gallery 291 and publication Camera Work which showed photographs as well as works by Rodin, Matisse, Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri Rousseau, Cézanne, Picasso and Picabia, was part of a worldwide movement of Pictorialism—to be understood in its derivation from the Latin verb pingere ‘to paint’—which sought legitimacy as art by emphasising painterly qualities through the photographer’s creative input in techniques such as soft focus, special printing processes, and radical composition to evoke emotional responses similar to those produced by fine art paintings.

George Bernard Shaw recounted how;

“At that time the impression produced was much greater than it could be at present; for the question whether photography was a fine art had then hardly been seriously posed. . . . Evans suddenly settled it at one blow for me by simply handing me one of his prints in platinotype.”

Peter Perry as director of the then Castlemaine Art Gallery and Historical Museum added to the collection photographs of artists, intended as pendants to exhibitions of their works. Amongst them is the work of Pegg Clarke, the life companion of painter Dora Wilson, also with works at CAM. They exhibited together and their collaboration is evident.

1968, when Scharf’s Art and Photography was released, was the year in which students moved into a barely-finished $1.5 million multi-storey building on High Street Prahran, with some starting in the newly established photography course in the basement.

Melbourne’s other photography school, which provided technical instruction in forensic, medical or architectural photography, was at RMIT where Lenton Parr was Head of Sculpture before in 1966 he was appointed Head of Art and Design at Prahran.

He introduced fashion and industrial design, and photography for which he appointed architectural photographer Ian McKenzie, and Paul Cox who was then living in what was to become The Photographers’ Gallery in Punt Road in 1973. As Cox describes it in his brief mention of the College in his Reflections: an autobiographical journey (1998):

“A local art school needed a part-time teacher to join their new photographic department. Some students had seen my photographs in the show window [of Paul’s Punt Road studio] and asked me to apply.”

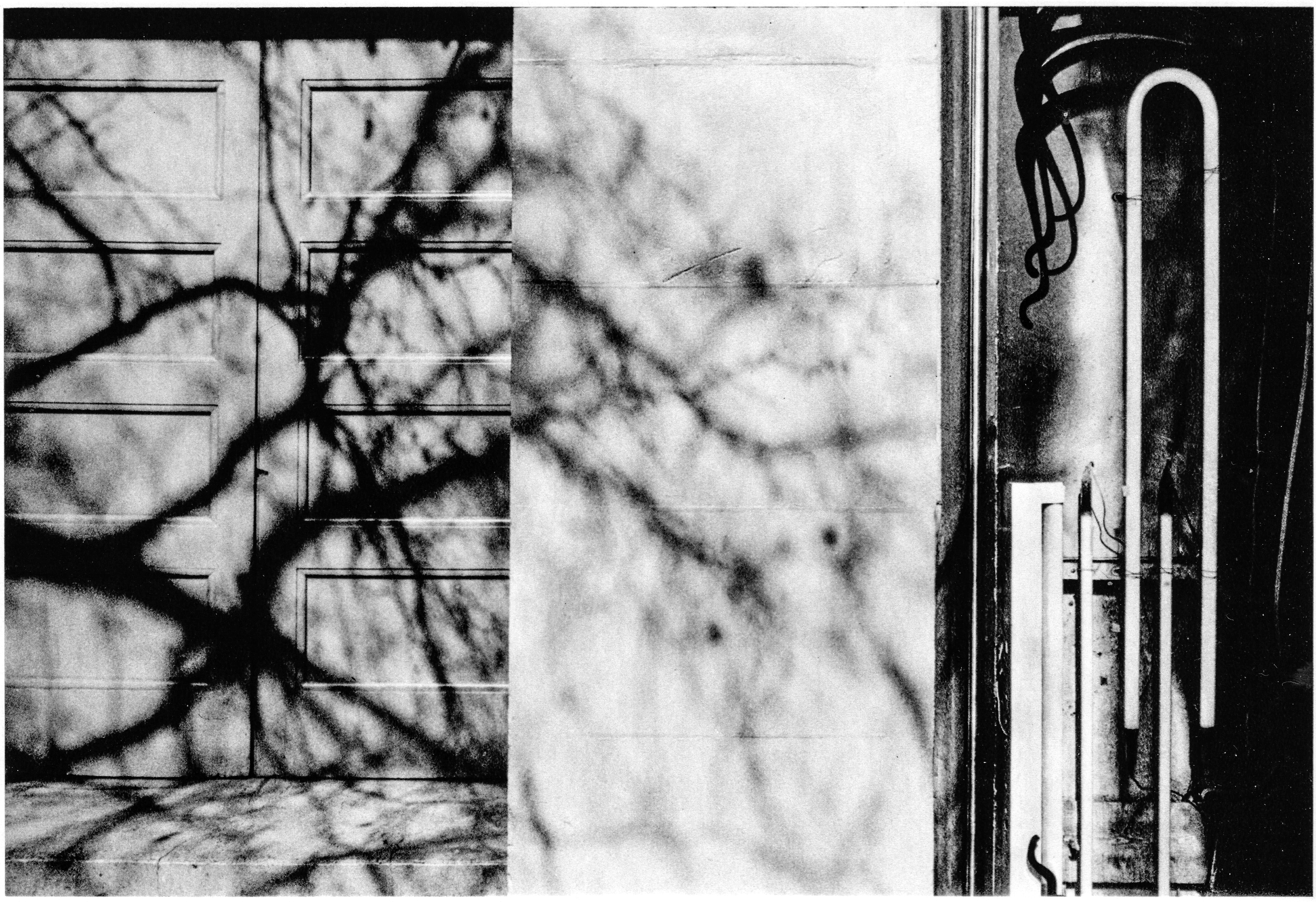

Cox’s own photography is that of an art-school educated European familiar with the post-war French and Dutch humanist, and the German Fotoform abstract photography, and surely knew of his compatriot the firebrand photographer-filmmaker Ed Van der Elsken.

At the age of 20 Paul had set out on extensive travels, first to London to work as a photographer then in the mid-60s he traveled to Australia on its immigration program via India, Nepal and Bali, stayed 18 months, studied at Melbourne University, fell in love, returned on a French cargo ship to Holland where he exhibited to good reviews by photo critic Willem K. Coumans, then returned to Australia and in 1966 started as a wedding-portrait photographer in his shop in Punt Road.

Cox remembers Lenton Parr as “a fine sculptor, a free thinker and visionary,” who made Prahran College “his Australian ‘Bauhaus'”:

“Until the authorities closed in on him, this college had a significant impact on the development of the arts in Australia. I was joined by my friend and mentor, Athol Shmith, and later by John Cato, who will one day be recognised as one of the true greats in the art of photography.

“When the faculty expanded and a lecturer in cinematography was needed, the job was mine. Apart from the few Super-8 movies I had made and some more serious attempts on 16mm, I knew nothing about filmmaking. I was forced to stay one step ahead of the students. That’s how I became a filmmaker.”

$12,404 ($161,300 in today’s money) worth of equipment was purchased for Paul’s teaching of cinema and his approach was to recruit his students as actors and crew on his early films. Julie Higginbotham and others are recorded here in Paul’s photographs of them working on Mirka:

One who benefitted from this approach was Carol Jerrems, whom Paul identifies as “his best student,” who appears in several of his photographs and in the films Skin Deep (1968) and The Journey (1972) in both cases as a lesbian, just as in her own tragically short life (1949-1980) she experimented with her sexuality and was known to put herself in danger in order to get her pictures.

An alumnus, Ian Macrae, who shared a house with Jerrems and became a filmmaker, remembers:

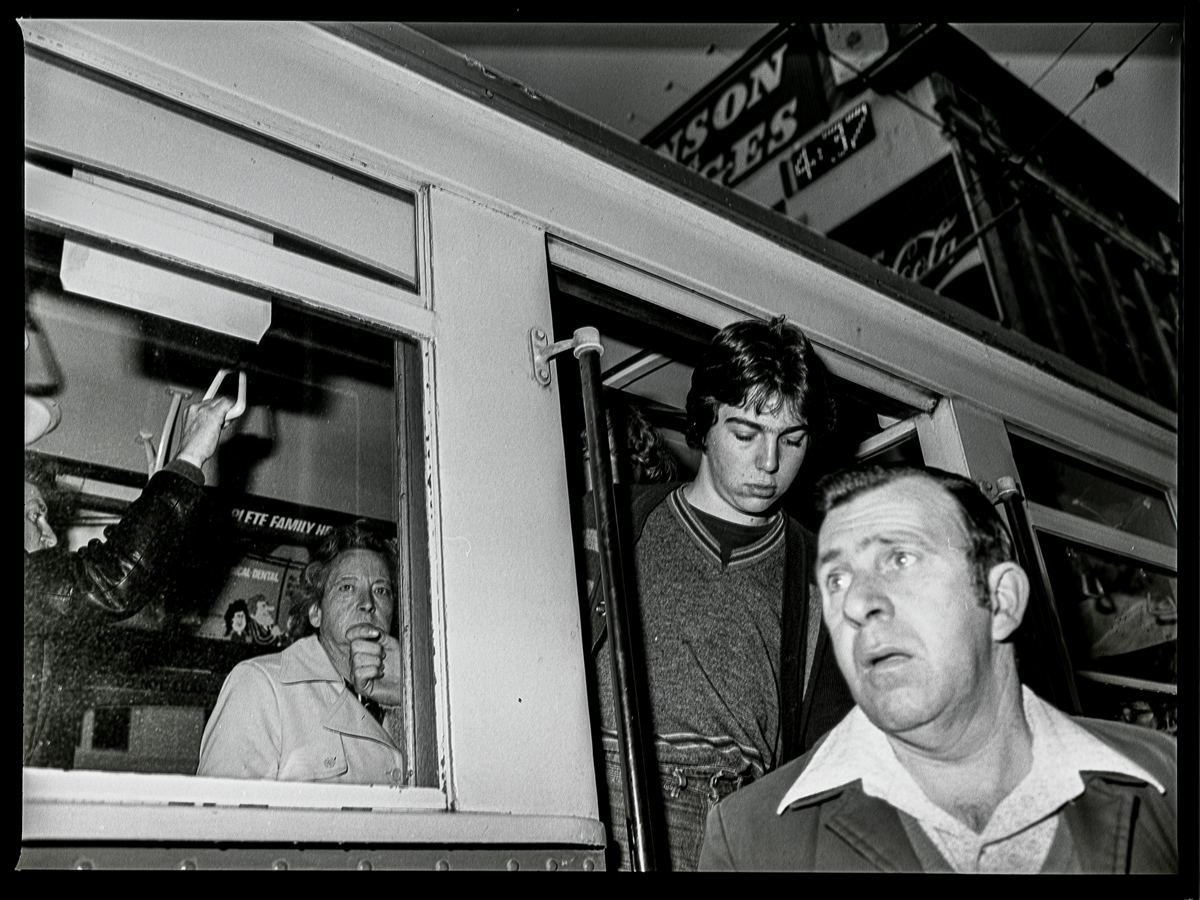

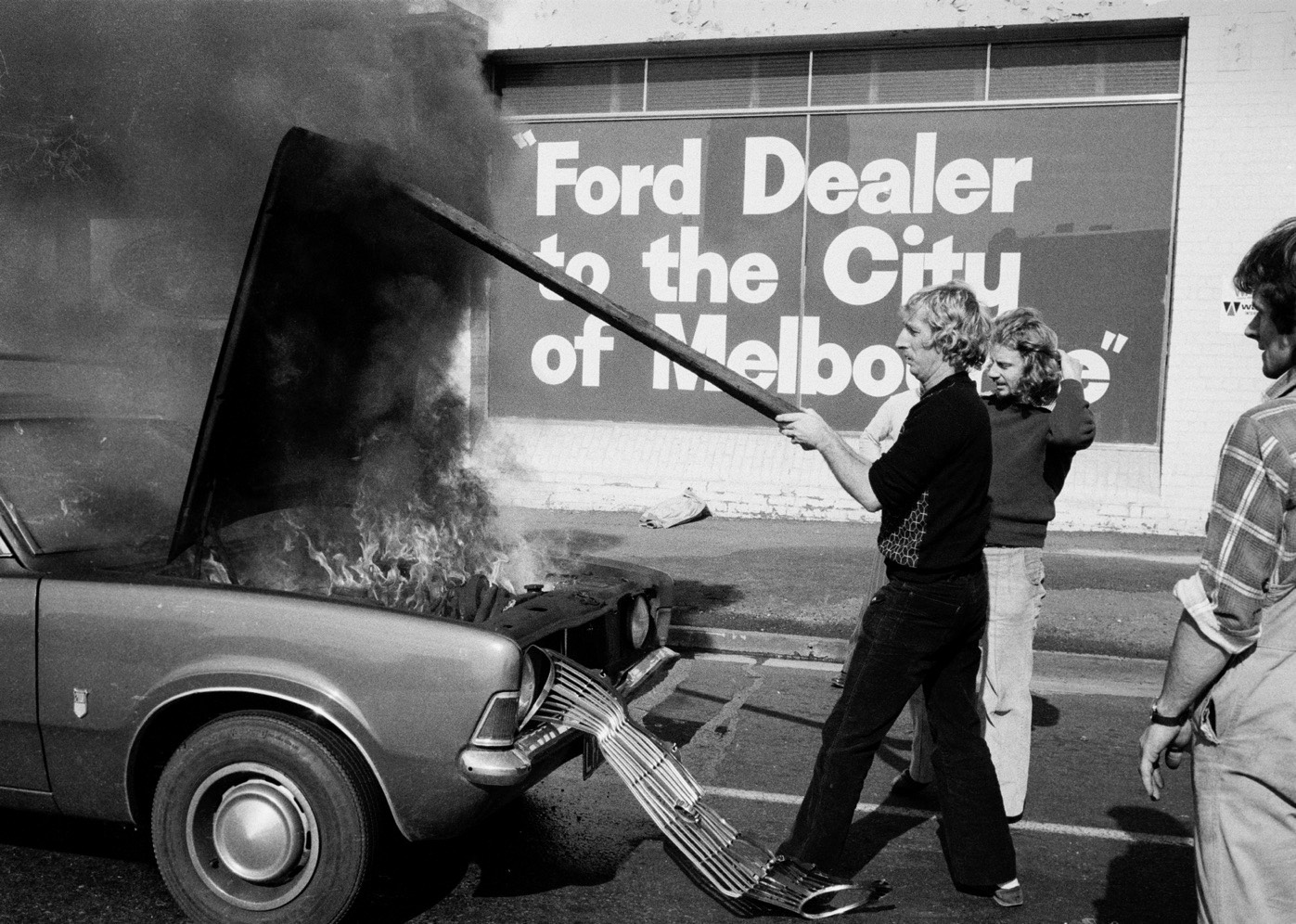

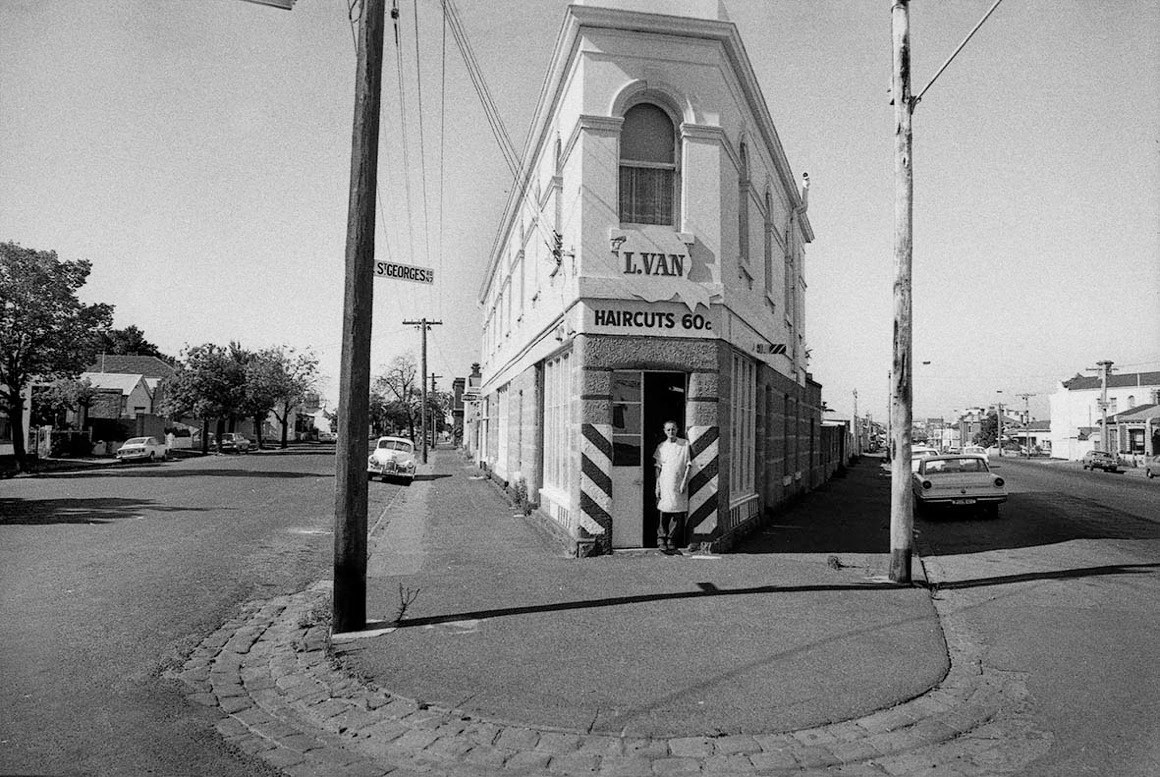

One thing Paul Cox had us do…was to go out to awkward, interesting places. I took photos in a notorious bar in Port Melbourne where all these guys were playing pool [and] at a gruesome abattoir. We found ourselves able to go out and take photos of people in those sort of environments and get their confidence, and build our own.

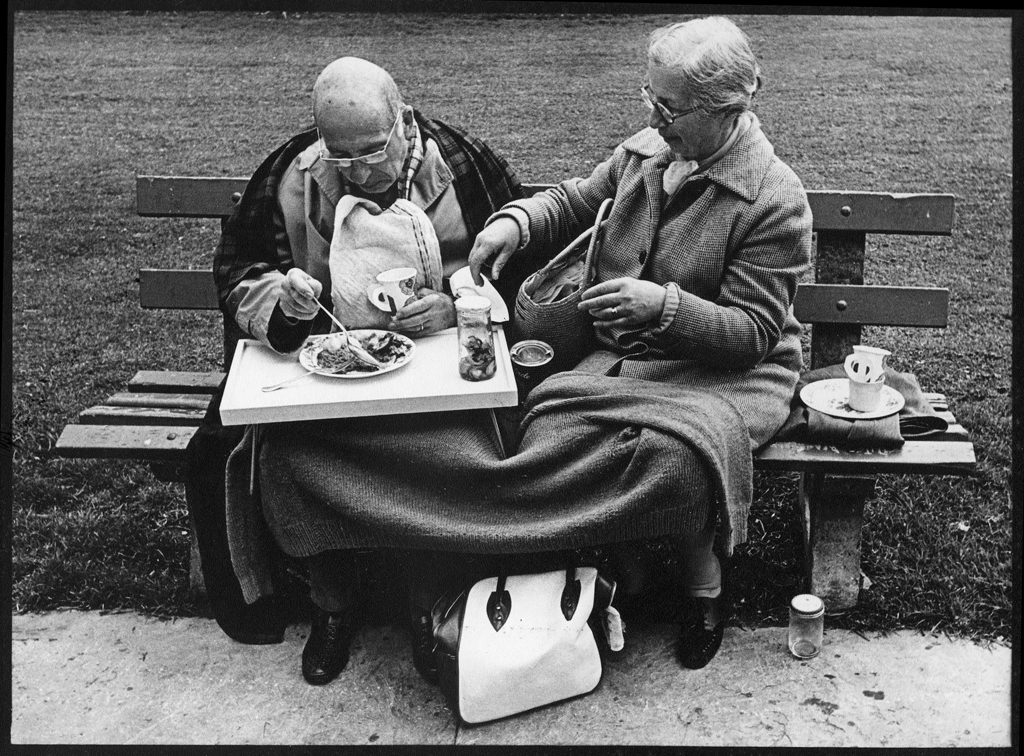

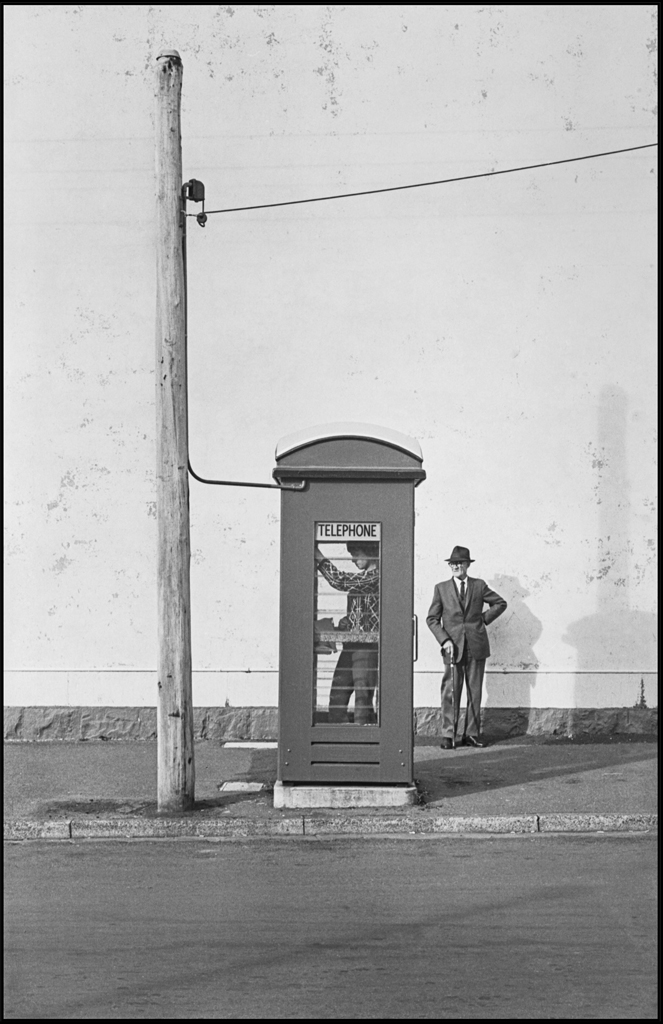

Street photography was a popular genre practiced by the students, and by Jerrems too, immersing themselves in the atmosphere of working class suburbs, as Prahran then was.

As Gael Newton recalls, when Jerrems’ Vale Street was first exhibited in a solo show at the Photographers’ Gallery over December 1975—January 1976, it was an instant hit and was purchased off the wall by the Australian National Gallery. It brought the highest price for an Australian photograph when it sold for $122,000 at a Sotheby’s Australia (now Smith & Singer) auction in November 2020. It was pivotal and signalled her transition from documentary towards a more subjective and collaborative approach that she had experienced from the other side of the camera in Cox’s films. A comparison with Cox’s anonymous nudes reveals Jerrems’ boldness in making hers real, a portrait.

One may trace a continuum of ever more constructed image from Vale Street to Prahran alumnus Bill Henson’s 1977-78 untitled, carefully orchestrated, cycle of works.

In 1974, cultural commentator Craig McGregor wrote that:

“It has taken a long time, in Australia… for photography to be accepted as an art. I am still not sure why this is so;…The ulterior reason…is the apparently representational nature of photography. Like, you click the shutter and get an exact picture of reality – where’s the art in that? The truth, of course, is that photography never has been merely representational and certainly is not today…Even when the photographer simply sets out to record reality, he [sic] is doomed to failure. Whether he wants to or not, he has to act like an artist […] In Australia, for instance, photographers such as Paul Cox and other Melbourne photographers who have been influenced by him deliberately manipulate images to create a desired, quite artificial result.” [Craig McGregor ‘Photography as Art” Art and Australia, Vol 11, No 4, Autumn 1974, p.354]

While Prahran College was thus an arena for this ‘renaissance,’ it was not focused just there, nor was it spontaneous, but had been emerging in the 1960s in the magazines like Australia’s answer to America’s LIFE, Walkabout which under my father Brian’s editorship through the decade, published photography by David Beal, Jeff and Mare Carter, Beverley Clifford, Gordon De Lisle, Max Dupain, Heather George, Helmut Gritscher, Laurence Le Guay, Robert McFarlane, David Moore, Lance Nelson, Graham Pizzey, Axel Poignant, Wolfgang Sievers, and Richard Woldendorp.

Art patron John Reed at his Museum of Modern Art Australia in Tavistock Place Melbourne held from 1961 series of shows of the photographs of Group M inspired in their experimental hanging by the global The Family of Man, still the most-seen photography exhibition with over 9 million visitors, when it traveled to Australia to the unlikely venue of the Preston Motors showroom on 23 February 1959.

The National Gallery of Victoria Department of Photography was established in April 1967 and was run part-time by fashion photographer Athol Shmith, photojournalist Les Gray and its committee Chairman, advertising photographer Dacre Stubbs, who along with sculptor Lenton Parr, then Head of Art and Design at Prahran College, oversaw the purchase of the photography collection’s first work, Australian photojournalist David Moore‘s modernist 1948 Surrey Hills street (purchased through the Kodak (Australasia) Pty Ltd Fund) and in 1971 the acquisition of their first international work František Drtikol‘s Nude (1939) in bromoil, a medium favoured by Pictorialists.

The Gallery’s first solo photographer’s exhibition was by Mark Strizic in 1968 and in 1971 curator Jennie Boddington acquired Jerrems’ Alphabet assignment set by her Prahran College lecturer Athol Shmith. It was a task which remained for several years one of the earliest in the Prahran first-year program and taught the crucial skill of seeing the world in two dimensions in the viewfinder, a conceptual leap now more readily made when photographing via the flat screen of a mobile phone.

Students also attended nearby Brummels Gallery, above a coffee shop in Toorak Road run by Rennie Ellis and Robert Ashton, which showed, amongst major Australian photography, student work by Robert Ashton, Peter Leiss, Carol Jerrems, Matthew NIckson, Euan McGillivray, Jacqueline Mitelman, Geoff Strong, Rod McNicol, Steven Lojewski and Gerard Groeneveld.

The Photographers’ Gallery started by Cox, John Williams, Rod McNicol and Ingeborg Tyssen was taken over in late 1974 by Australian born Ian Lobb who had undertaken workshops with Ansel Adams and Paul Caponigro, and American Bill Heimerman whom Lobb met when with Jerrems when they taught together at Coburg Technical School.

During the 1970s they showed American photographers Larry Clark, Brett Weston, Paul Caponigro, Edna Bullock, Wynn Bullock, Aaron Siskind, Ralph Gibson, Paul Caponigro, Jerry Uelsmann, Robert Cumming, Harry Callahan, Emmet Gowin, Eliot Porter, William Clift, John Divola, Lee Friedlander; Europeans Lisette Model, Franco Fontana and Édouard Boubat; and the Japanese Eikoh Hosoe amongst which they showed Prahran students Andrew Wittner, Steven Lojewski, Graham Howe, Gerard Groenveld, Bill Henson, Geoff Strong, Carol Jerrems, and Peter Leiss, and their lecturers Paul Cox and John Cato.

In 1976 Joyce Evans opened Church Street Photographic Centre, a specialist photography gallery and bookshop in Church Street, Richmond, Victoria as the third commercial photographic gallery in 1970s Melbourne.

By the end of the decade Christine Golden, referring back to Craig McGregor’s 1974 perspective and also acknowledging Prahran College, wrote that:

“In 1980 it is no longer possible to make [a] clear separation between artist and artist-photographer. The younger Australians, aware not only of the dominant American tradition in photography but also of current American and European developments in the arts, produce pictures that require a sophisticated and informed audience. The accepted notion, that photography is somehow simpler to understand and easier to enjoy, results in baffled, bored and sometimes angry reactions to the more complex contemporary work.” (Christine Godden ‘Photography in the Australian Art Scene,’ Art and Australia, Vol 18, No 2, Summer 1980-2, p. 175)

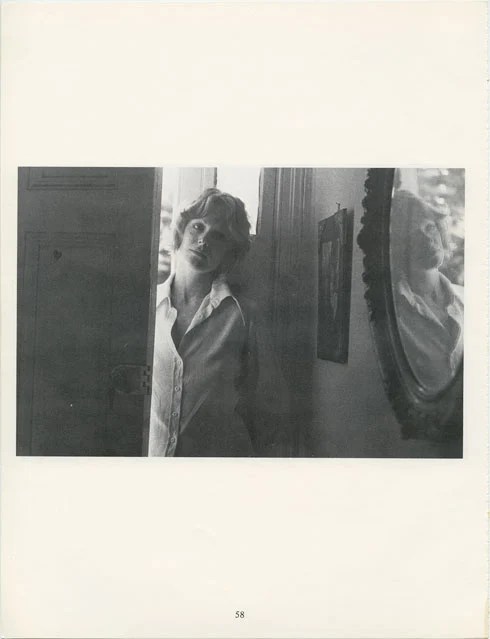

Australian portrait photographer Jacqueline Mitelman, born McGregor, in Scotland, studied for a Diploma of Art and Design at Prahran College of Advanced Education 1973-76, where her lecturers were Athol Shmith, Paul Cox, and John Cato. She had been briefly married to Alan Mitelman who had graduated from Prahran in 1968 and later lectured in printmaking at the Victorian College of the Arts before its merger with Prahran visual arts in 1992.

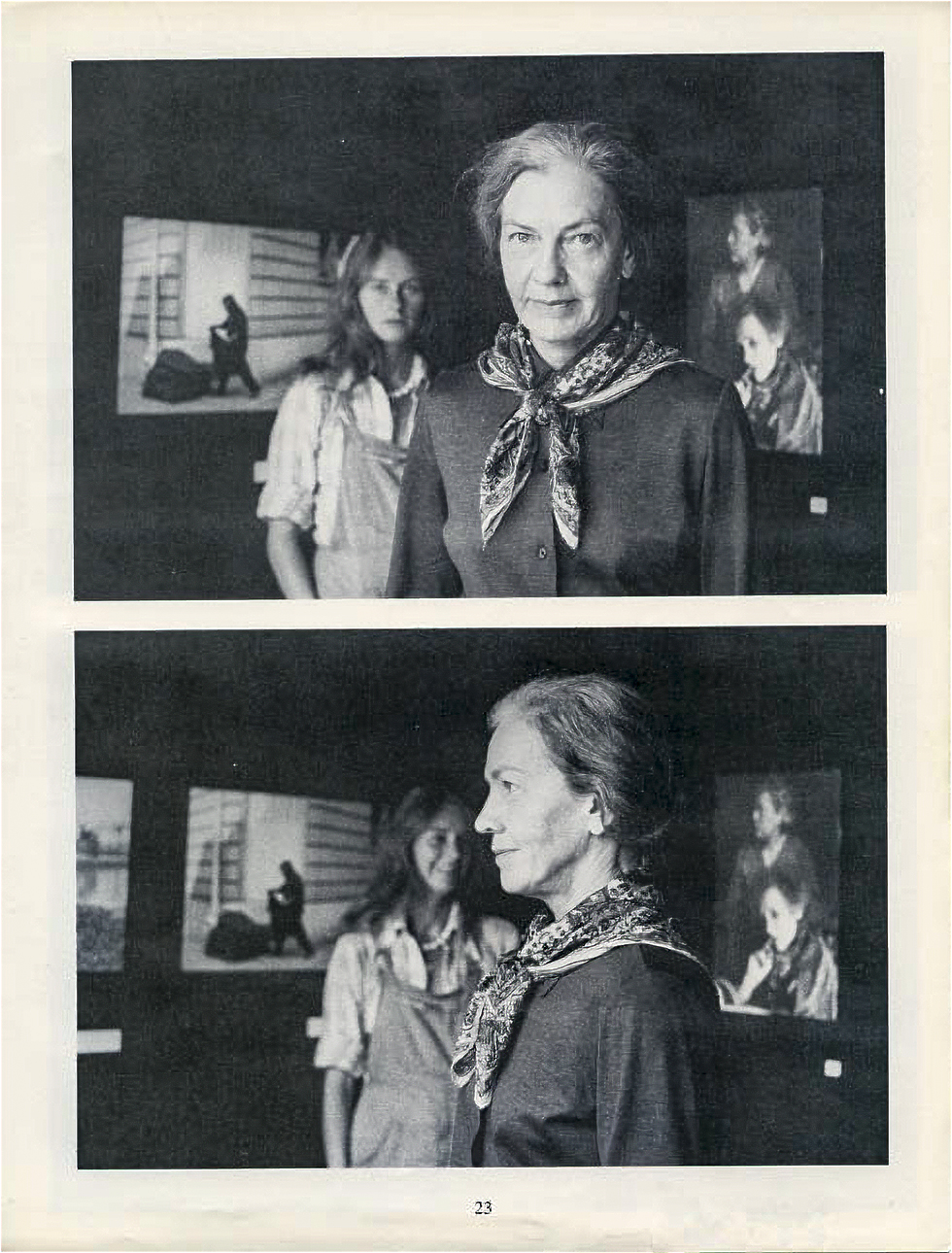

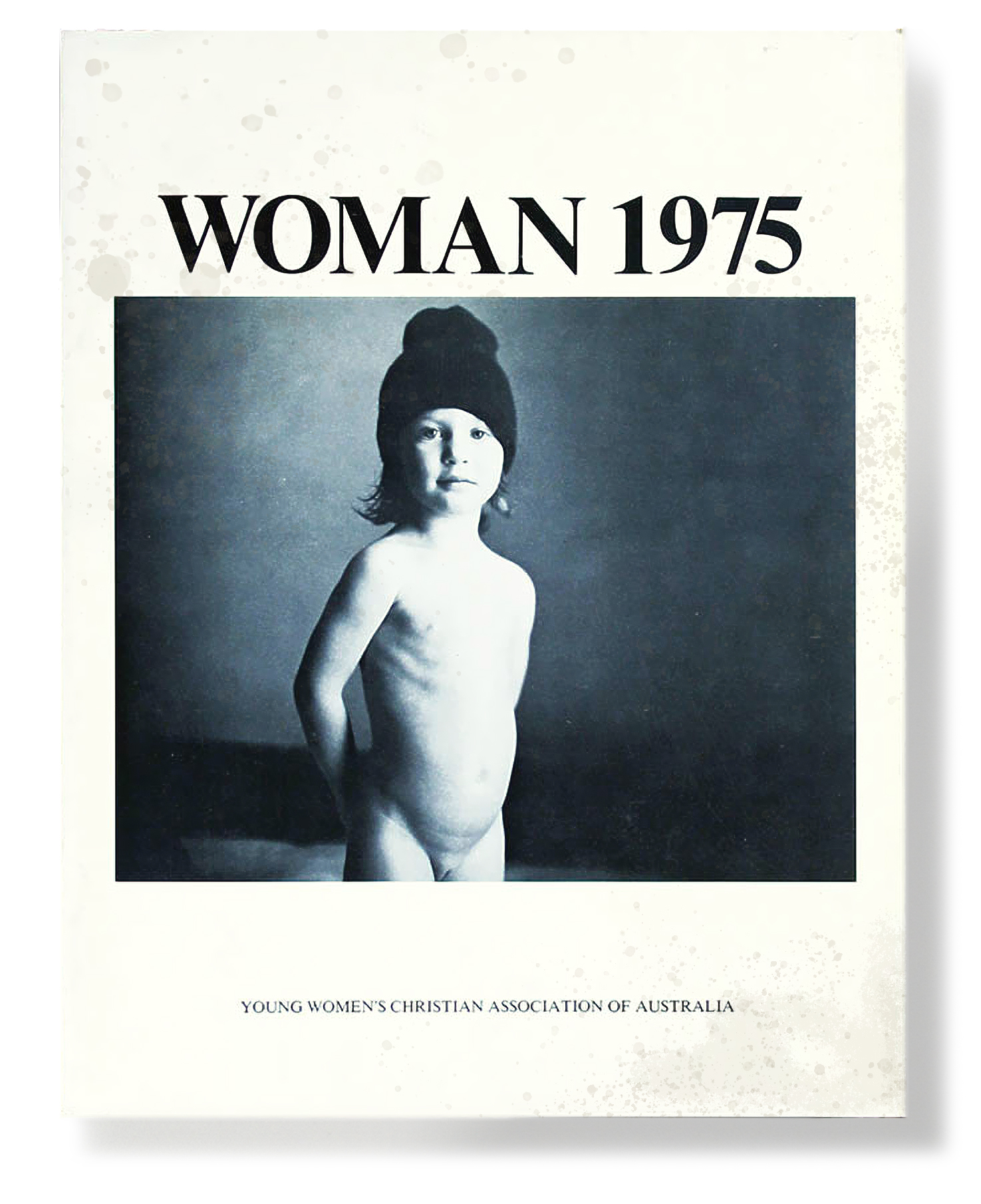

In July 1974 Jacqueline exhibited with fellow Prahran College photography students Matthew Nickson and Euan McGillivray at Brummels Gallery. The next year she showed work in the group exhibitions Woman 1975, which toured, auspiced by the Young Women’s Christian Association of Australia, and at the National Gallery of Victoria in an exhibition curated by Boddington, also for International Women’s Year; Wimmin: six wimmin photographers, with Fiona Hall, Marion Hardman, Melanie Le Guay, Melanie Nunn, and also Ingeborg Tyssen, who with Cox had started The Photographers’ Gallery near Prahran College.

Carol Jerrems had photographed Mitelman for her own International Women’s Year publication A Book about Australian Women.

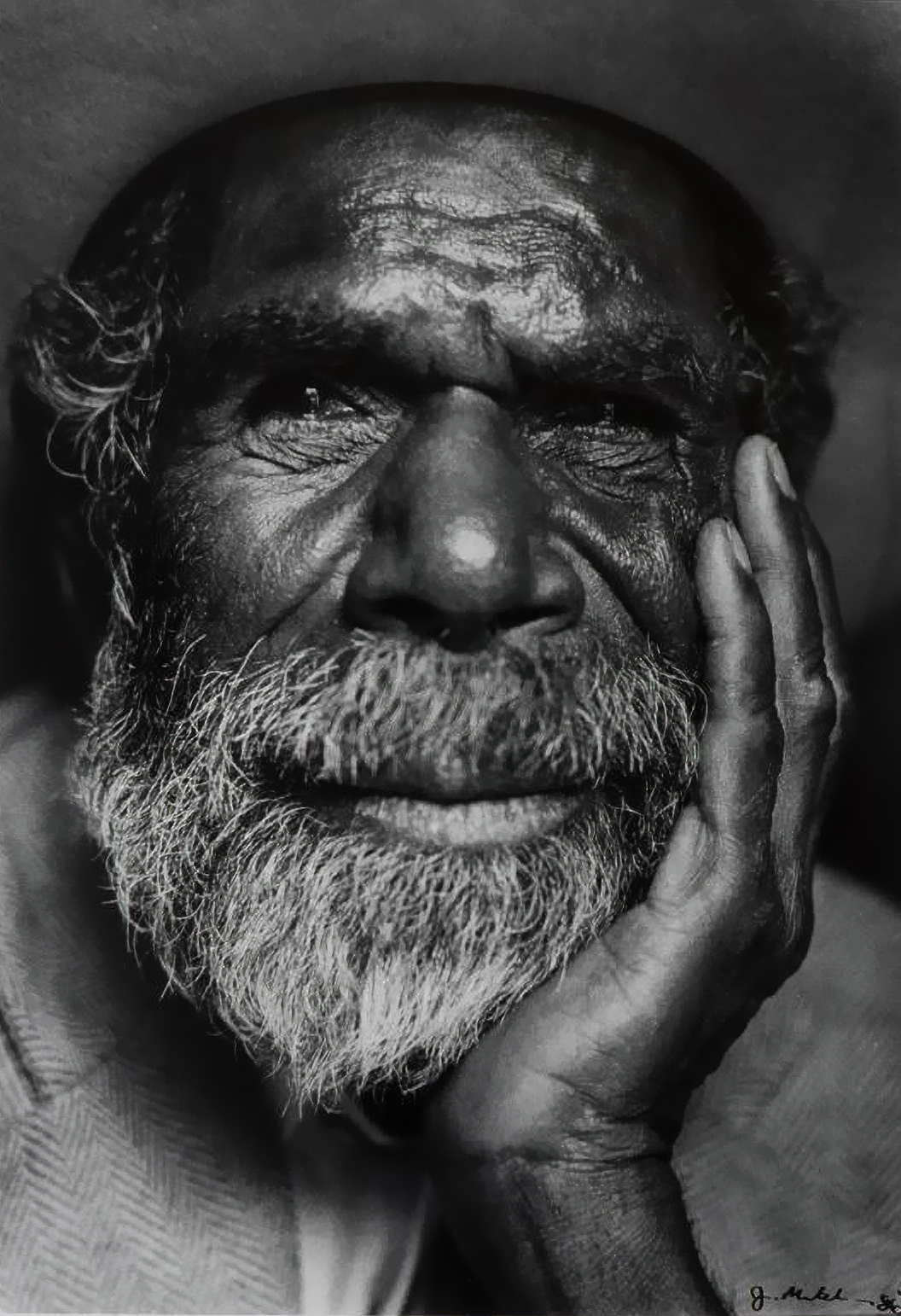

After graduation, Mitelman practiced as a freelance photographer specialising in portraiture for magazines and newspapers, album and book covers, and for theatre and music posters. After a lukewarm reaction to her work in an Age newspaper review by fellow Prahran alumnus Greg Neville, Mitelman softened with more expressive results in later examples which include Paddy Carroll Tjungurrayi a Pintupi artist who contributed significantly to the Western Desert art movement,

Castlemaine Art Museum, purchased 1994. Accession number PC73

…and also her portrait of Brett Whiteley, which are both in the CAM collection.

One of the most penetrating of Mitelman’s portraits is that of her lecturer Paul Cox, with whom she remained a firm friend after leaving Prahran. His last film, of the same year, 2015, when Mitelman took this photograph, was fatefully titled Force of Destiny. It drew on his own experience of life-threatening illness, painful treatments, then a liver transplant, following cancer, which calamitously returned in the new organ. The film was also a tribute to his will to continue working and living.

His frailty is evident as he huddles against his pain, and his legendary vitality remains barely glimmering in his steady, determined gaze into Mitelman’s lens, yet he loved it, she reports, because it bears the aura of his great hero Vincent Van Gogh.

Investigations into the Australian tertiary sector reveal ongoing challenges in accommodating the unique needs of creative arts students within traditional university structures. Reports indicate that these institutions often struggle to provide the supportive environments necessary for fostering creativity and artistic practice.

The Prahran experience for the majority was positive. Students moved through the 3-year course as a cohort and regarded themselves as amongst colleagues with whom they made friendships and built networks that have survived half a century, as they now enter their 70s. Classes continued through the week, and included on-location assignments and group projects, as well as electives in other media. Certainly a sense of competition was promoted, especially in the open group assessment process, but in general that was constructive. Many, like Paul Lambeth, recount how lecturers’ interest in and encouragement of them continued well beyond their College days.

The Prahran entity ceased to be from 1 January 1992 when an Act of Parliament brought Victoria College’s Prahran Campus and Prahran College of TAFE under the auspices of Swinburne University of Technology, with the only tertiary courses, Graphics and Industrial Design, remaining on the campus. All others were moved to Deakin University except Prahran Fine Art under Gareth Sansom which was relocated and amalgamated with the Victorian College of the Arts, where the next Dean of Art was William Kelly.

As the VCA was not split into departments, it was the Prahran heads who were given the role in several cases, with Pam Hallandal becoming Head of Drawing, Head of Ceramics was Greg Wain, previously Head of Ceramics at Prahran, and Victor Majzner likewise became Head of Painting at the VCA. , and with John Cato’s retirement Prahran Graduate Christopher Köller was newly appointed as head of their new department of Photography.

The VCA was merged with the University of Melbourne in 2007 as part of a broader trend in higher education to consolidate specialised institutions with larger universities to streamline administration and ostensibly to share resources and enhance opportunities for students.

The Australian Universities Accord Interim Report, released in July 2023, identified the misalignment between the specialised nature of art education and the broader university frameworks. This has led to difficulties in maintaining the unique identity and pedagogical approaches of art schools within larger university structures.

One comprehensive study Artists as Workers: An Economic Study of Professional Artists in Australia by David Throsby and Katya Petetskayaby for the Australia Council for the Arts highlights significant economic and professional challenges faced by artists, suggesting that the current university system inadequately supports their development. The report emphasises that artists encounter precarious employment conditions, limited financial stability, and insufficient institutional support, despite their high skill levels and the societal value placed on their work

Recent studies have highlighted significant challenges faced by visual arts students in Australian universities, particularly concerning their mental health and wellbeing. A notable report is the “Visual Arts Wellbeing Project” by Eileen Siddins whose conclusions from a comprehensive wellbeing needs assessment of visual art students were that that the university environment often fails to meet the specific needs of these students, and she makes recommendations for enhancing their mental health, resilience, and overall university experience, especially in their level of engagement, sense of meaning leading to positive emotions, in relationships, and a sense of accomplishment. There is a pressing need for targeted reforms to better support visual arts education within the higher education framework.

A look backwards, through this exhibition and publication at the evident success half a century ago of art schools like Prahran could constructively inform such assessments and actions. Geoff Strong’s perceptive remarks about the value of ‘prismatic thinking’ as engendered by the traditional art school are germane.

Angela Connor and Stella Loftus-Hill, curators at the Museum of Australian Photography (MAPh), believe that their exhibition in March-May 2025, and accompanying hardback catalogue and its texts, will be of historical importance in displaying photographic documentation and expression of the 1970s, its new wave of feminism, sexual freedoms, ever-louder anti-war rhetoric, its thwarted swing to the left in politics, new music, conceptual and performance art (which in the following decade was to become ‘post-modernism’) all of which whet students’ passions and coursed through their imagery that they produced on threadbare budgets.

Angela Connor and Stella Loftus-Hill, curators at the Museum of Australian Photography (MAPh), believe that their exhibition in March-May 2025, and accompanying hardback catalogue and its texts, will be of historical importance in displaying photographic documentation and expression of the 1970s, its new wave of feminism, sexual freedoms, ever-louder anti-war rhetoric, its thwarted swing to the left in politics, new music, conceptual and performance art (which in the following decade was to become ‘post-modernism’) all of which whet students’ passions and coursed through their imagery that they produced on threadbare budgets.

Your thoughts are welcome…

Hi

No content in this mail, Cheers

Sandra Graham sandragraham.aus@gmail.com

>

LikeLike

Hi Sandra, thanks for letting me know. WordPress generates the emails. The post mentioned is at https://prahranlegacy.org/2024/06/20/discussion-photography-in-the-art-school/

Regards,

James

LikeLike