It’s here: The Basement, the book! The first delivery of the limited edition, I believe, is already sold out, but more are on the way.

It’s appropriate that Anouska Phizacklea, MAPh Director introduces it, as she does in her Foreword to this historical record of the photography course—started in the basement of this small art school—which was ground zero of an explosion of art in photography in Australia:

“From its establishment in the late 1960s through to the early 1980s, the Photography Department at Prahran College of Advanced Education was a catalyst for expanding creative photographic practice in Australia. Under the vanguard of influential photographers such as John Cato, Paul Cox and Athol Shmith, the school became a breeding ground for some of this country’s most important art photographers. Against the backdrop of huge political and cultural change, these artists have gone on to shape Australian art and art education.

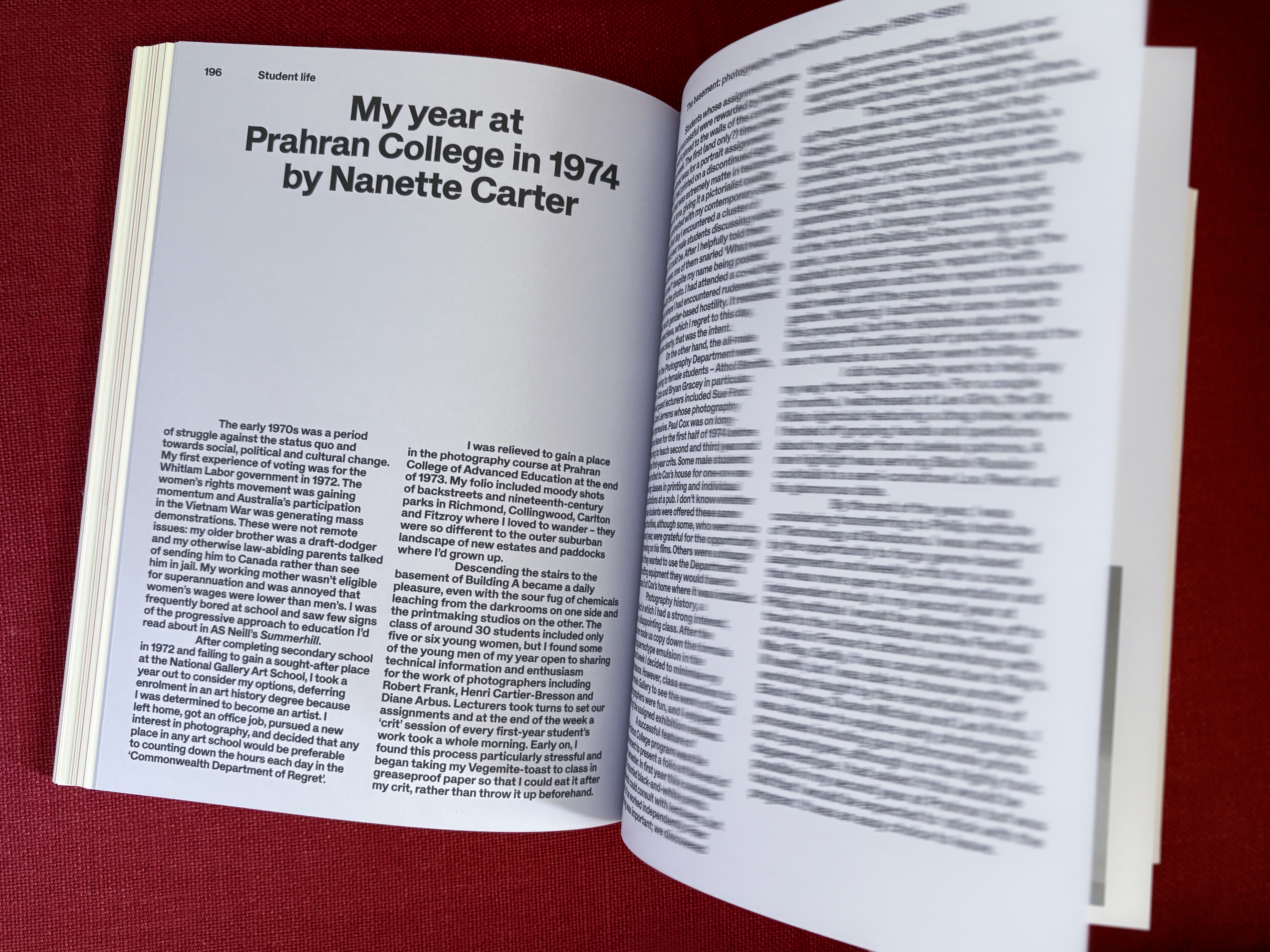

“Through a selection of insightful essays and first-hand accounts, this publication brings together a number of respected scholars, curators and artists. Helen Ennis provides cultural context through the back stories of some of the teachers at Prahran College; Gael Newton describes her observations as a young curator at the time; Daniel Palmer shares his research on the gallery scene between the 1960s and 1980s in Melbourne; Nanette Carter, James McArdle and Nicholas Nedelkopoulos recall their experiences as students at Prahran College; Adrian Danks writes about the influence of Paul Cox and his films; and Susan van Wyk interviews Bill Henson, one of the most renowned artists to come out of the College. The book includes a wonderful array of photographs and student portfolios, some of which haven’t been seen since they were produced and exhibited in the 1970 and early 1980s.”

[. . .]

“Our sincere thanks go to the City of Monash for its continuous support. We are particularly grateful for the generous support of our publication partners, Colin Abbott, Andrew Penn AO and Kallie Blauhorn, and the Gordon Darling Foundation who have made this important publication possible.”

In the book curators Angela Connor and Stella Loftus-Hills follow Anouska Phizacklea with their joint introduction. The text, while it covers every section shown on the gallery walls, deviates slightly in sequence from the curators’ organisation of the exhibition itself from which the illustrated works are taken, and which are supported by the fine quality of the reproduction of the mixed monochrome and colour images.

That finesse is a tribute to Wilco Art Books of Amersfoort in The Netherlands; on the matt, slightly warm-toned paper blacks are dense, detail crisp and colours are rich, albeit slightly more muted than they would be on a glossy stock which, had that been selected, would have broken the equilibrium of the tightly curated design.

That is the work of Paul Mylecharane whose many clients, beside MAPh, include the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art; Artspace (Sydney); A Published Event; Behind the Wire; Bus Projects; ETH University (Zürich); Institute for Contemporary Art (Graz); Kunsthaus Erfurt; Liquid Architecture; MUMA Monash; Neon Parc; Next Wave; Occasional Papers (London); Onomatopee (Eindhoven); Open Humanities Press; Perimeter Editions; RMIT University; Soft Opening (London); Surpllus Editions; Un Projects; University of Melbourne; University of Western Sydney; and Van Abbemuseum (Amsterdam).

Paul’s take on 1970s photography and design is carried through in his use of a safelight-red paper stock that drenches the bold black type as if it were a print immersed in a tray of developer. The red pages visually announce the beginning of each of the chapters and sections and form an excellent visual index complimentary to Sherrey Quinn‘s comprehensive text index; in every way this book is a resource for which future researchers into 1970s photography will be grateful! The expertise invested in The Basement is of the highest order.

A visitor to the show encounters first a wall of images devoted to the theme ‘A Time Of Hope’, and in the book that is illuminated by the writing of art historians Helen Ennis, who examines ‘Interconnections: the early years’ and Daniel Palmer, who surveys ‘The gallery seen: photography exhibitions in Melbourne 1960s-1980s’.

For ‘The New Photography’ which is housed in the second gallery, Gael Newton provides a more national perspective in her ‘Prahran College and Melbourne, a visitor’s view’, and we return to the other walls of the opening where hang the ‘Down on the Street’ collection, and Stella Loftus-Hills’ essay ‘Finding their voices on the street’.

The exhibition is interspersed with moving images, and the film productions of the College staff and students are acknowledged in Adrian Danks‘ ‘A student of cinema: Paul Cox at Prahran College’.

In the exhibition, a partitioned space is devoted to works from the MAPh collection by the lecturers Paul, Athol, and John, with the addition of a print by the lecturer whose tenure extended beyond all of theirs; Derrick Lee. Their images face Carol Jerrems‘ Alphabet series, an evidence the impact of their provocative teaching and challenging assignments.

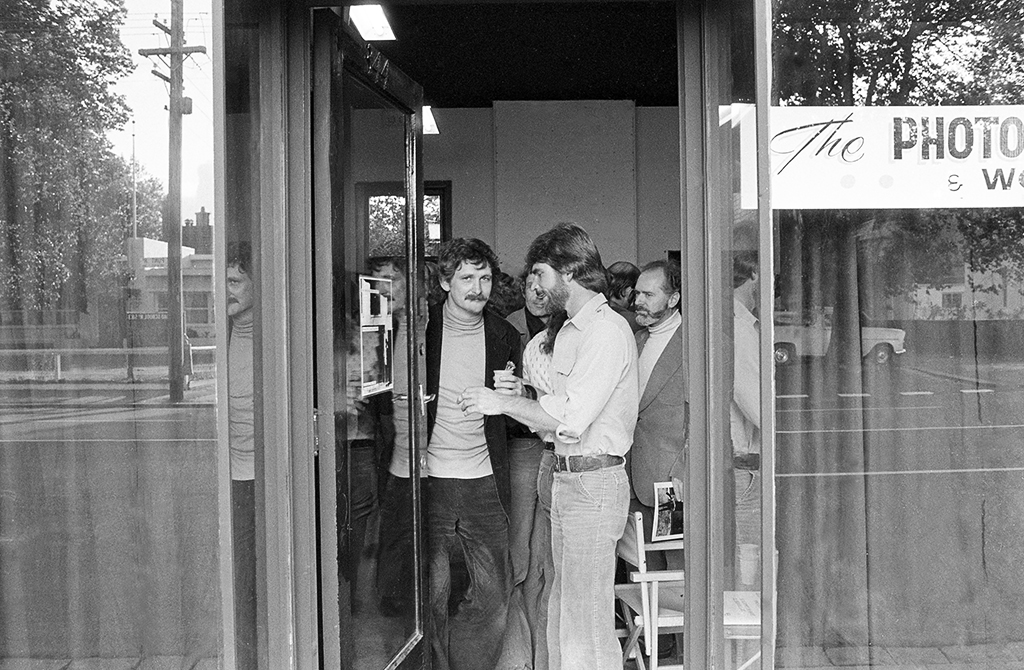

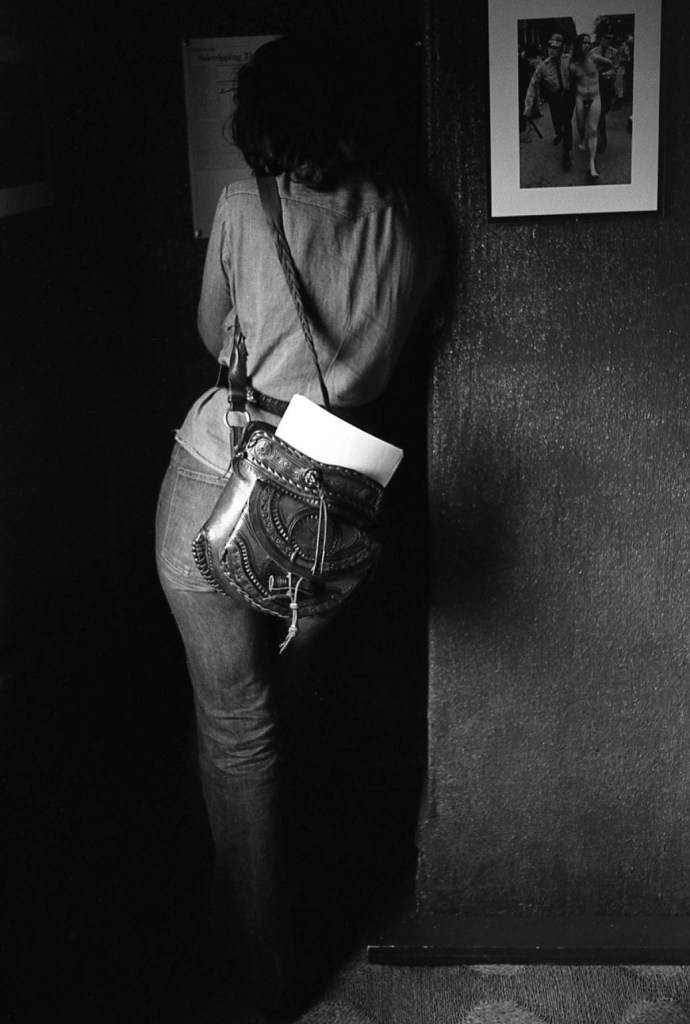

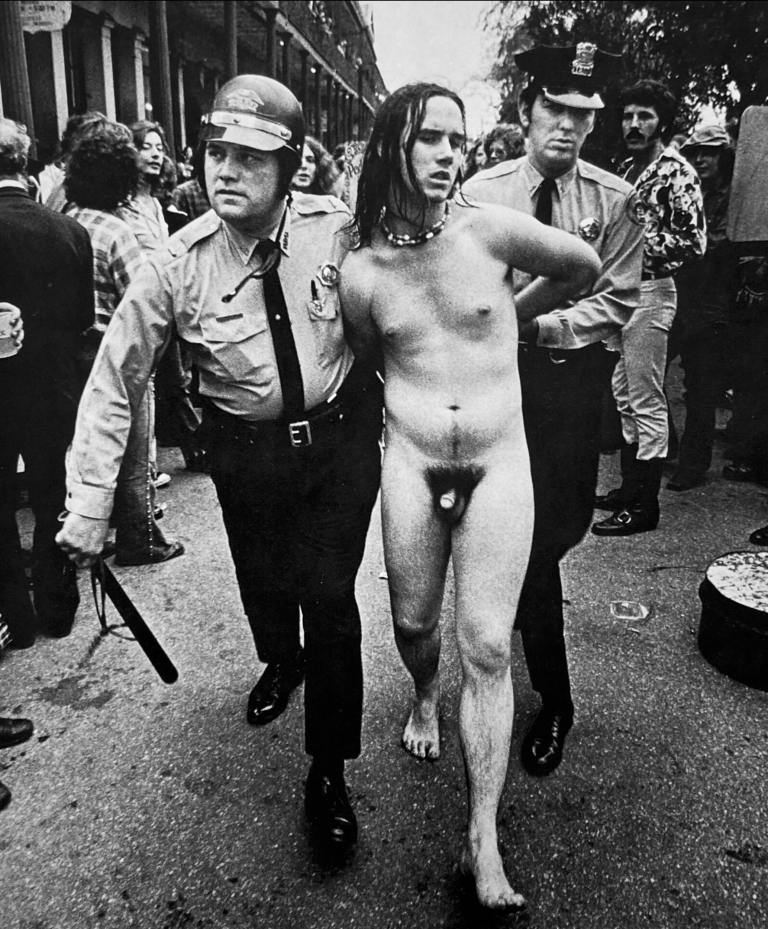

In the book, the first images encountered are portraits of Shmith and Cox by Rod McNicol, and one of Cato by Shmith, followed by pages of mostly candid or impromptu vignettes of them amongst the students and representative samples of their own work. These flow, behind the muted-olive title page for ‘A Time of Hope’, into a series of pictures by students, of students. We are pulled up at Peter Bowes’ back view of a visitor to Sidetripping at Rennie Ellis’s and Robert Ashton‘s Brummels Gallery, themselves back-to-back with the streaker in Charles Gatewood’s famous, more tightly cropped 1973 photograph. The American image in Australia’s first private gallery of photography faces the red title page of Helen Ennis’s chapter ‘Intersections: the early years’ and is a reminder of the dominance of the U.S. over us, in the 1970s.

Ennis examines photography education at Prahran during Australia’s social transformation of the late 1960s and early 1970s, but challenges the narrative that innovation stemmed exclusively from youth, instead emphasising productive intergenerational exchanges between students and their older educators. Where Donald Horne characterised Australia as “racist, anglocentric-imperialist, puritan, sexist, political genteel—acquiescent, capitalist, bureaucratic and developmentalist,” Prahran represented a space of creative possibility and hope.

Prahran’s pedagogical innovations are traced to earlier developments in the 1950s, when commercial photographers like Athol Shmith formed alternative collectives outside conservative professional organisations—what Max Dupain (see Helen’s recent Max Dupain: a Portrait) termed a “revolt;” early initiatives that established a collegiality that was later central to Prahran’s educational philosophy. The school’s head, Lenton Parr, described as “a free thinker and visionary,” implemented Socratic teaching methods and a multidisciplinary approach that integrated photography with other art forms in what Paul Cox praised as an “Australian Bauhaus.”

Ennis details how Prahran’s educators—particularly Shmith, John Cato, and Cox—contributed, despite belonging to what historian Ian Turner identified as the “ten per cent minority” amid youth-dominated cultural movements. These educators maintained open-door policies, socialised with students, and were themselves evolving as artists. Their approach incorporated historical awareness; Shmith served on the committee advising the National Gallery of Victoria’s Department of Photography, while Cato brought historical knowledge influenced by his father Jack Cato, author of Australia’s first photography history.

Ennis’s is not an uncritically celebratory narrative or institutional hagiography; it acknowledges Prahran’s limitations. Student Greg Neville found the curriculum “not well designed,” while Bill Henson “rarely attended classes because he found them irrelevant.” Most critically, Ennis addresses the gender imbalance, noting examination records from 1974 showing only five of twenty students were female, with the first woman (Julie Millowick) not appointed to teach until 1983. She contextualises this within broader Australian sexism while noting that women like Sue Ford were creating significant work outside institutional frameworks, deliberately positioning themselves beyond such constraints.

The scholarly tone of Ennis’s essay balances appreciation for Prahran’s innovations with critical examination of its shortcomings, actively acknowledging dissenting views and gender disparities. In concluding with a symbolic reference to a photograph of young Caroline Slade from Jerrems’ 1975 International Women’s Year publication A book about Australian women, she points to the “hopeful future” to come, despite the documented limitations—hers is a nuanced treatment of both Prahran’s progressive aspirations and its failure to fully transcend contemporaneous social and art world inequities.

The title of Daniel Palmer’s “The Gallery Seen” is characteristic of his wry humour that so lightly carries the underlying density of his research evident in his several book publications and in this critical analysis of Prahran’s exhibition landscape that expands on his and Martyn Jolly’s encyclopaedic Installation View. He tells how these galleries helped legitimise photography as an art form while providing crucial platforms for emerging photographers. Palmer advises that when he arrived in Melbourne from Perth in 1997, Prahran’s photographic heyday had already faded in the shadow of developments in Sydney. That sets up a contrast between his retrospective view and the dynamic period that he experienced directly.

Palmer frames the 1970s as a transformative era for Australian society and photography, characterised by social activism, the progressive Whitlam government’s policies (1972-1975), abolished university fees, and expanded cultural funding. This created what Palmer describes as perhaps “the best moment to be young and creative in Australia,” with affordable rents and unemployment benefits serving as “quasi arts grants” that allowed creative experimentation. While acknowledging middle-class white men dominated the scene, Palmer positions the photography boom as one of the baby boomers’ most significant cultural legacies.

The essay details three independent photography galleries that operated within kilometers of Prahran College: Brummels Gallery of Photography, The Photographers’ Gallery and Workshop, and Church Street Photographic Centre. Palmer argues these spaces were crucial when “physically visiting exhibitions of photography was the main way to discover what was happening” in pre-internet times. As Australia’s first independent photography gallery, Brummels (established 1972 by Rennie Ellis) played a pivotal role in exhibiting Prahran student work, including Carol Jerrems, Rod McNicol, Steven Lojewski, and others. Palmer cites Ellis’s ambition “to align photography with the fine arts in helping Australians towards self-definition and development,” positioning these galleries within broader cultural nationalism.

Validation of its institutions was critical to photography’s growing status, a process commenced with the National Gallery of Victoria’s groundbreaking Department of Photography (established 1967) following lobbying by photographers including Athol Shmith. The NGV’s 1968 exhibitions, including The photographer’s eye from MoMA, coincided with Prahran College’s first photography student intake, establishing crucial synergies. Jennie Boddington‘s appointment as the NGV’s first photography curator in 1972 further strengthened Prahran connections, evidenced by her acquisition of Jerrems’s Alphabet portfolio produced as a college assignment.

The essay is particularly insightful about intergenerational relationships in Australian photography. Palmer describes how commercial photographers like Shmith, Paul Cox, and John Cato transitioned toward creative practice and teaching at Prahran, creating bridges between commercial and art photography. Dutch-born Cox exemplifies this transition; after establishing a portrait studio in South Yarra (later the site of The Photographers’ Gallery); his provocative nude window display being literally gate-crashed by a car allegedly “endeared him to the students” from nearby Prahran College.

Palmer agrees with Ennis in acknowledging a significant gender imbalance in this photographic world, noting it was “very much a man’s world in the 1960s and 1970s, while women were often the object of its gaze”. However, he balances this observation by highlighting pioneering women photographers, including Sue Ford (first woman with a solo show at NGV in 1974) and Jerrems, whose “Vale street” later became the highest-selling Australian photograph at auction while elsewhere noting that a NGV trustee described photography as “a cheat’s way of doing a painting”.

While Palmer acknowledges his historical distance from events, his research details the commercial challenges faced by independent galleries and the period’s gender politics. He more directly experienced the postmodern move away from the raw, self-expressive imagery of the early 1970s toward the more self-conscious and conceptually driven work often influenced by international trends and theoretical discourses. This transition involved a greater awareness of photography’s constructed nature and its relationship to broader cultural and political contexts. This shift inevitably impacted the College, influencing subsequent generations of students and shaping the critical frameworks through which photography was taught and understood, but by 1988 Geoff Strong‘s rear view through The thousand mile stare was of a divisive factionalism breaking out at the end of the 1970s. Palmer confirms that “tensions between and within fine art, documentary and commercial approaches to photography were alive and well” by the time of Prahran’s merger with the VCA and when he was working at the former Victorian Centre for Photography.

Gael Newton’s essay “Prahran College and Melbourne, a visitor’s view” is a concise, reflective and engaging account of the vibrant photography scene in Sydney and Melbourne during the mid-1970s to mid-1980s, centred on the influential role of Prahran College. It surveys the scene from a wider perspective. From her experiences as the first curator of photography at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, she feels that both cities thrived on a youthful enthusiasm for “New Photography,” enriched by an environment where senior photographers, educators, and emerging artists interacted dynamically. Newton highlights the diverse and passionate nature of the Prahran College community, where an unstructured curriculum and open debates encouraged multiple approaches—from documentary and still life to collage and staged tableau—while the influence of European cinematic sensibilities and the local film and music scenes added depth to the artistic expression.

Newton analyses individuals’ experiments with collage and colour photography in the exhibition; innovative works such as John Brash’s “Carlisle St” with its retro American road-trip feel and Leonie Reisberg’s constructed image “Mythological Dream,” which combined a cut-out of a colour Polaroid with a black-and-white print to create a layered, symbolic narrative. The discussion extends to the ‘social history’ genre, noting how images of protest marches and parades capture more than just the attitudes of participants—they also serve as rich records of the social milieu in such examples as Graham Howe’s Moratorium image of 1971 that prompt reflection on the era’s political and cultural dynamics.

Gael writes engagingly from personal recollections, this blog’s survey of former students, examples of influential works, and experience of the motivating charisma of Athol Shmith, John Cato, and Paul Cox, to underscore the lasting impact of their teaching and creative legacies. While she acknowledges challenges—like the limited presence of First Nations students, gender discrimination in professional opportunities, and the difficulties inherent in sustaining dedicated photographic spaces—Newton notes that early pessimistic predictions about art students’ career prospects were disproved, as many alumni enjoyed successful and diverse professional lives. While both critical and celebratory, balancing nostalgia with a clear-eyed assessment of institutional shortcomings and the need for proactive efforts to preserve this dynamic legacy, she emphasises the urgency of ensuring that the cumulative energy and innovation of the Prahran photographers be recognised within the broader narrative of Australian art.

Space, and your attention, forbids reviewing here the content of Adrian Danks’, Angela Connor’s and Stella Loftus-Hills’ essays in the book which warrant a separate future post.

Nor should we pre-disclose here the conversation between Bill Henson and Susan van Wyk, or the colourful memories of alumni Carter, Nedelkopoulos and McArdle that are set out on Paul Mylecharane’s mauve paper (purple prose perhaps?)—instead, reserve your copies at the MAPh online shop and you will receive them when reinforcements arrive from The Netherlands! The limited-edition book will become a collector’s item, and should be in the hands of anyone serious or curious about Australian photography.

5 thoughts on “The book”