As a child, I would play with toy cars on the floor of my father Richard’s office, as he drew with a nibbed pen and pressed Letraset onto the page to create graphic images for advertising agencies.

As a child, I would play with toy cars on the floor of my father Richard’s office, as he drew with a nibbed pen and pressed Letraset onto the page to create graphic images for advertising agencies.

I was a lazy kid and marvelled at his ability to earn a living with the stroke of a pen—he even let me create a symbol, that he improved on, for one of his clients and bought me an ice-cream—more wonderful still was the seemingly effortless way Richard Beck created iconic images and his bold refusal to bargain when agency heads balked at his prices.

The Coonawarra wine label, featuring a woodcut of the winery, is still the most recognisable Australian wine label, more than 70 years after the company was forced to build the path that my father imagined for it, when visitors, perplexed, asked why they couldn’t find it on the property.

The curator of a 2012 exhibition of historic Olympic posters, unaware of my relationship with my dad, confided in me that his 1956 Olympic Games poster was his favourite amongst posters by David Hockney, Andy Warhol and Roy Lichenstein. That example was why I decided at an early age not to strive to be famous, but to be respected by my peers in whatever I did, just like my father, who never promoted himself, which was another trait I admired.

After freelancing for most of his working life in England and Australia where he became a leading modern designer of the 1950s and 1960s, he took a job teaching graphic art at Prahran College in 1969 for which he designed its logo.

After a heart attack in 1972, he left teaching to resume his graphic design career at the age of 60, but, like music and fashion, times had changed and younger designers, some whom my father taught, were in vogue.

He got some work but he turned to other creative ways to make a living while my mother, after raising four children during the time of one income households, took on various jobs and created a catering business to make up the difference.

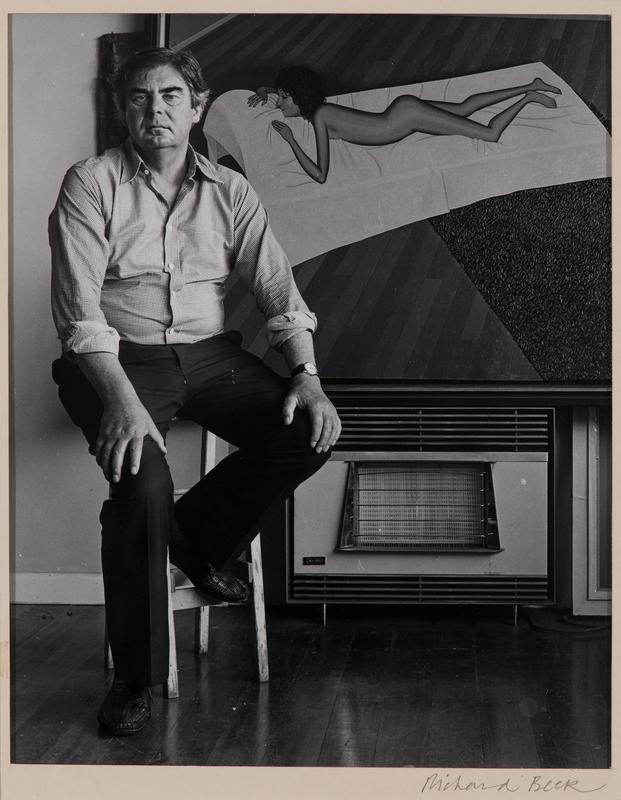

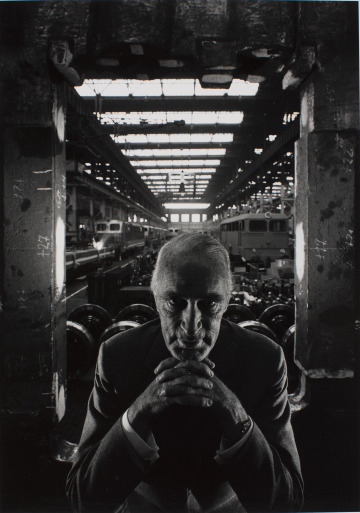

He was friends or acquaintances with many artists and struck on the idea of immortalising them in their studios with his trusty Rolleiflex and selling the images to the Victorian National Gallery for prosperity.

His photographs of artists, including Brett Whiteley and Fred Williams, are housed in galleries and museums in Australia, while his graphic design and posters are internationally displayed, including at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

He built a darkroom in a bedroom vacated by my older siblings and got to work. I developed an interest in photography as a teenager helping my father, sloshing the prints in and out of chemicals.

As a 16-year-old, I had been accepted at RMIT on the strength, I found out later, of my father’s legacy. The head of the art department discovered early on that despite my heritage, apart from amusing cartoons, I had no ability with the fundamentals of drawing, painting or sculpture. Far from being demoralised I turned to photography, and Mushroom Records and independent labels gave me some work photographing bands.

My fledgling career was cut short by a mental illness that saw me in and out of hospital for seven years in my 20s. My father died in 1985, before I dragged myself out of insanity and vowed to use the inventiveness, he had nurtured in me from the darkroom and his favourite armchair. He would draw on a pipe as he nestled a glass of red and quietly entertained with stories about history, artists and their art, his days as a camouflage expert in Tahiti during WW2 and the Quakers, who he admired for their simplicity and humanity. He never boasted about the awards he received or the admiration of his fellow and upcoming designers (he was posthumously, the first inductee, with fellow designer Les Mason, in the AGDA Graphic Art Hall of Fame in 1992).

Between mental breakdowns, I was accepted in the photography degree at Prahran College in 1984 on the strength of a folio, that my father looked over and encouraged me to present. This time John Cato, the head of the photographic department excused himself from deliberation because he knew my father, but I scraped into the final 16 anyway.

I was the only student to fail the first assignment. It was a simple project to introduce ourselves. I took the concept a bit too far and presented 10 images of close ups of my face in various guises. I don’t remember them all but there was one with my head tightened with reams of glad wrap and anther blowing smoke rings; happy sad, angry, frustrated. I’m not sure why I did it because I never told anyone there about my mental history, even after the facial horror was unveiled. I watched on nervously as students showed pictures of themselves surfing or even moving house – sociable images. A hush enveloped the room and my cheeks flared red. The students and John Cato were subjected to small bizarre images of my contorted facial expressions poorly mounted on flimsy card. I have always worked very quickly and had no patience for bevelled edged mounts. The humiliation was compounded by my shyness. It took me months to show any personality when I started at a school. After about three months I would open up and transform into a talkative, friendly chap. I remember one student told me she thought I was mute initially. So, I had to repeat the first assignment because my photos were considered poorly executed and probably ridiculous to those unaware of my mental condition.

Further exercises, including colourising black and white photos, bored me stiff. But the one tutorial that gave me hope was former student, Julie Millowick’s photojournalism class. I had already been a huge fan of Bill Brandt, with his high-contrast, imaginative portraits, and I was aware of Max Dupain and Olive Cotton and I followed some of the better Age photographers such as Catherine Tremain and Michael Rayner, but Julie introduced me to compelling photojournalism from Bruce Davidson, Robert Frank, Elliot Erwitt and Arnold Newman. Life—not news about disaster or dispute—but life as we live it.

I was intrigued by the moral dilemma for two brothers Mark and Dan Jury who had photographed their family for years, when their grandfather developed dementia. Should they produce images that could humiliate their family? They decided to continue and the series was full of love, humour and understanding. Julie illuminated the process, thought and morality behind photographic series and portraits that told stories about humanity.

I also remember the class analysing images – how they were created and the intent behind them. Arnold Newman’s clever portraits that visually explained something about the subject, included the powerful image of Alfred Krupp in 1963. Newman was commissioned by Newsweek to take a portrait of Alfred Krupp, a convicted Nazi war criminal. At first, the Jewish Newman refused, but eventually, he decided to take the assignment as a form of personal revenge. The resulting portrait became one of the most controversial and significant images of its time.

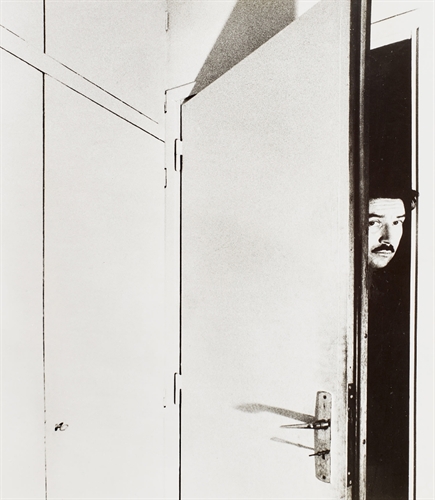

So much to digest in Julie’s class. There was also some overthinking. We discussed Bill Brandt’s methods and the meaning behind some of his portraits. The French writer and filmmaker Alain Robbe-Grillet poked his head through a door and we decided Brandt was expressing a voyeurism, the prying eye of the writer, thinker and director who kept his eye on the world surreptitiously. It turned out that the room was too small to fit them both, so Robbe-Grillet was forced to peer through an open door. Practical matters were also a consideration in the best photographs. I immersed myself in the work of the greats of photojournalism.

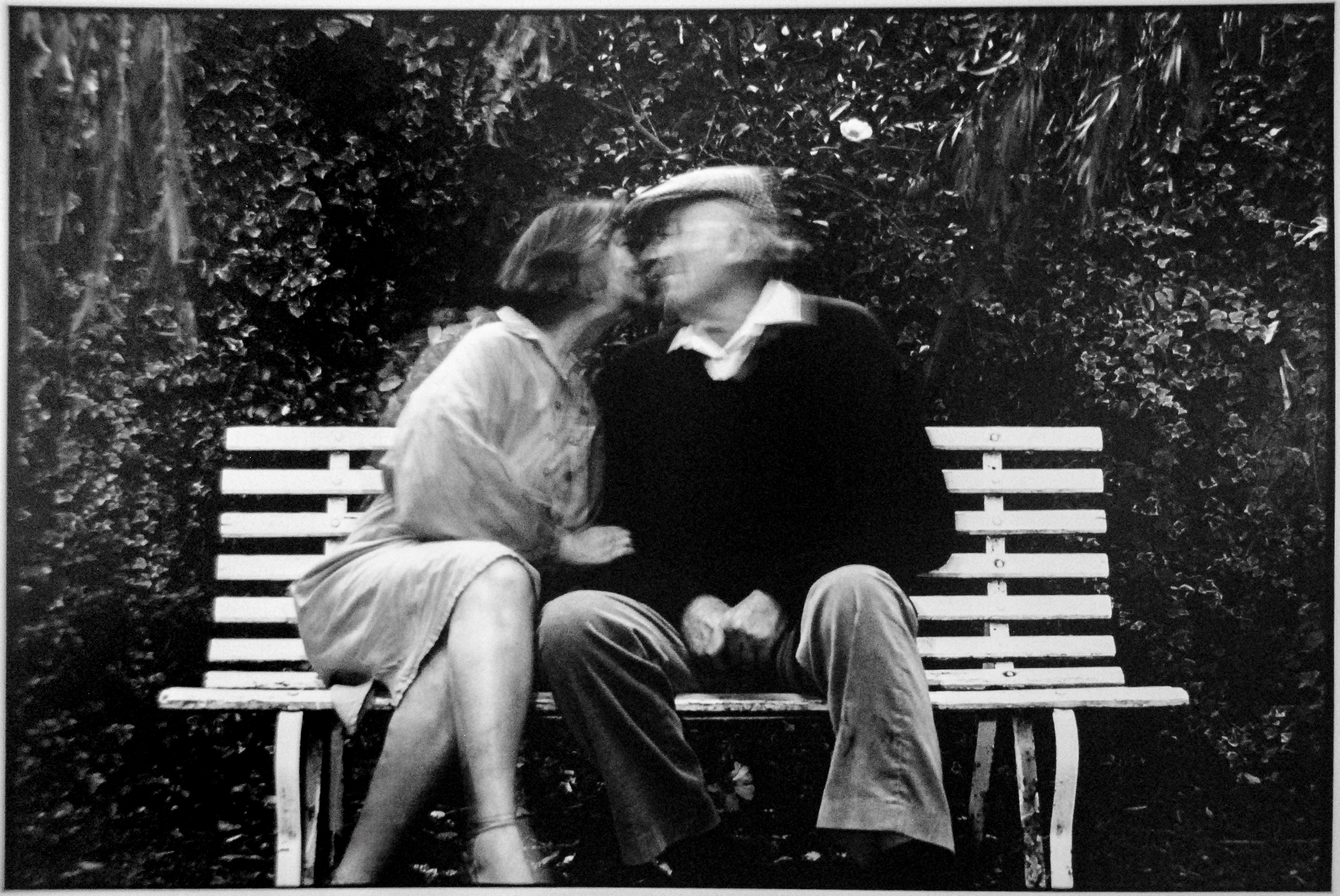

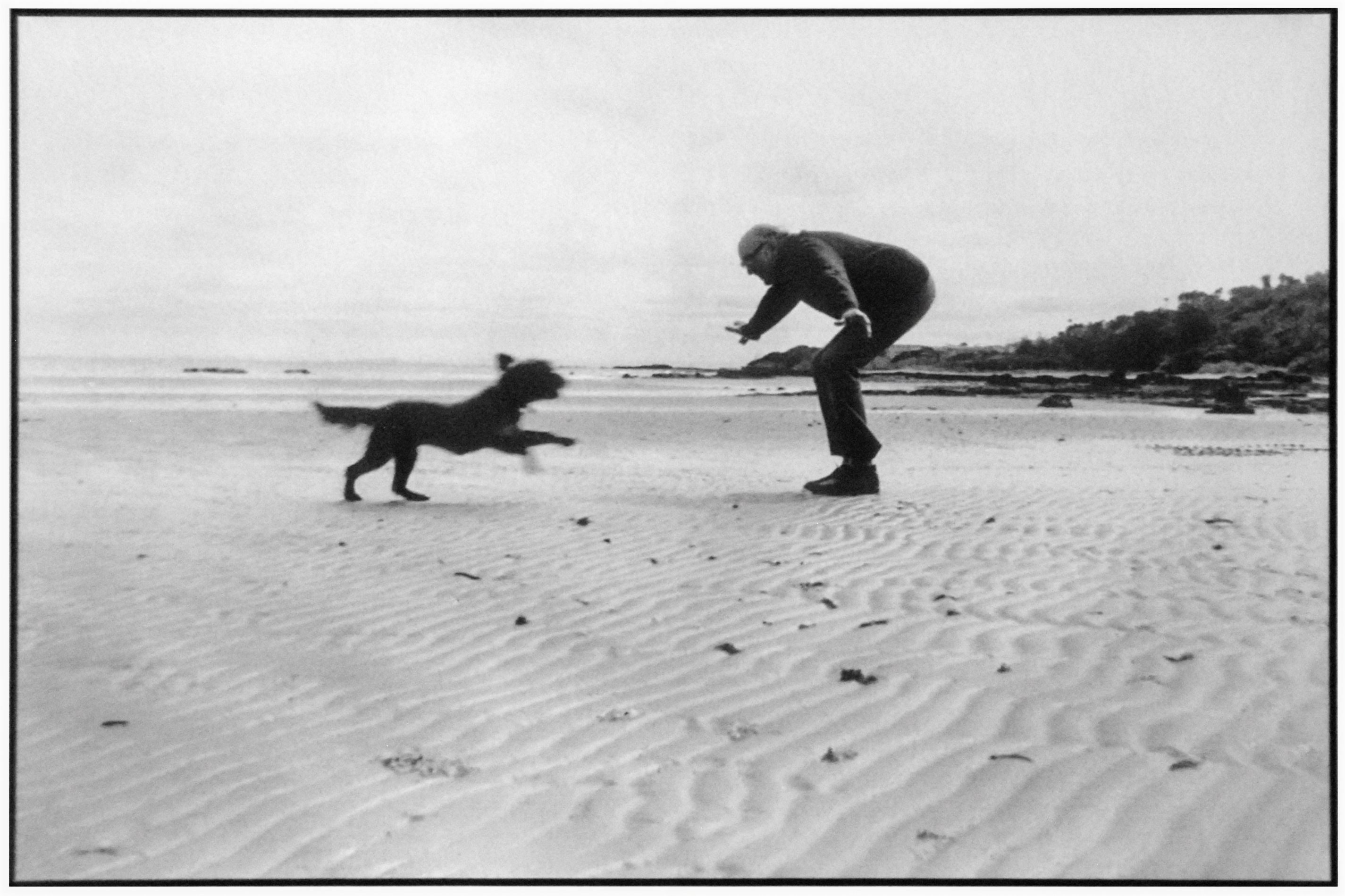

For my next assignment I created a pictorial series about my parents who were significant opposites. My father was a shy man who enjoyed solitude and despite having a good sense of humour was known for getting the joke a week later. My mother was a bright, talkative woman more interested in other people than herself. Photos of her surrounded by people and him alone on the beach, him contemplating with glass of red hand and her happily chatting with a cup of tea and biscuit concluded with them together on a bench kissing. That is one of only two of my photos I framed for my wall. The other is from my next assignment, a series of people’s relationship with their dogs (I later published a likeminded book). My father was in in poor health in his 70s and our dog was 16 and they walked gingerly around the house and napped together every afternoon. But every morning they let loose on the beach and I captured them in a joyous moment.

It was becoming clear I had no interest in the pure art of photography. I wanted to tell stories about people, life as we believe it to be or don’t. John Cato had a stern but understanding talk with me and I left Prahran College before the end of first year to pursue my calling. A couple more mental breakdowns and the death of my father later, I found some determination to defy my mood disorder. It hung around in a lesser way for the rest of my life but I learned to live with it by being more stringent with medication. It was time to make a change.

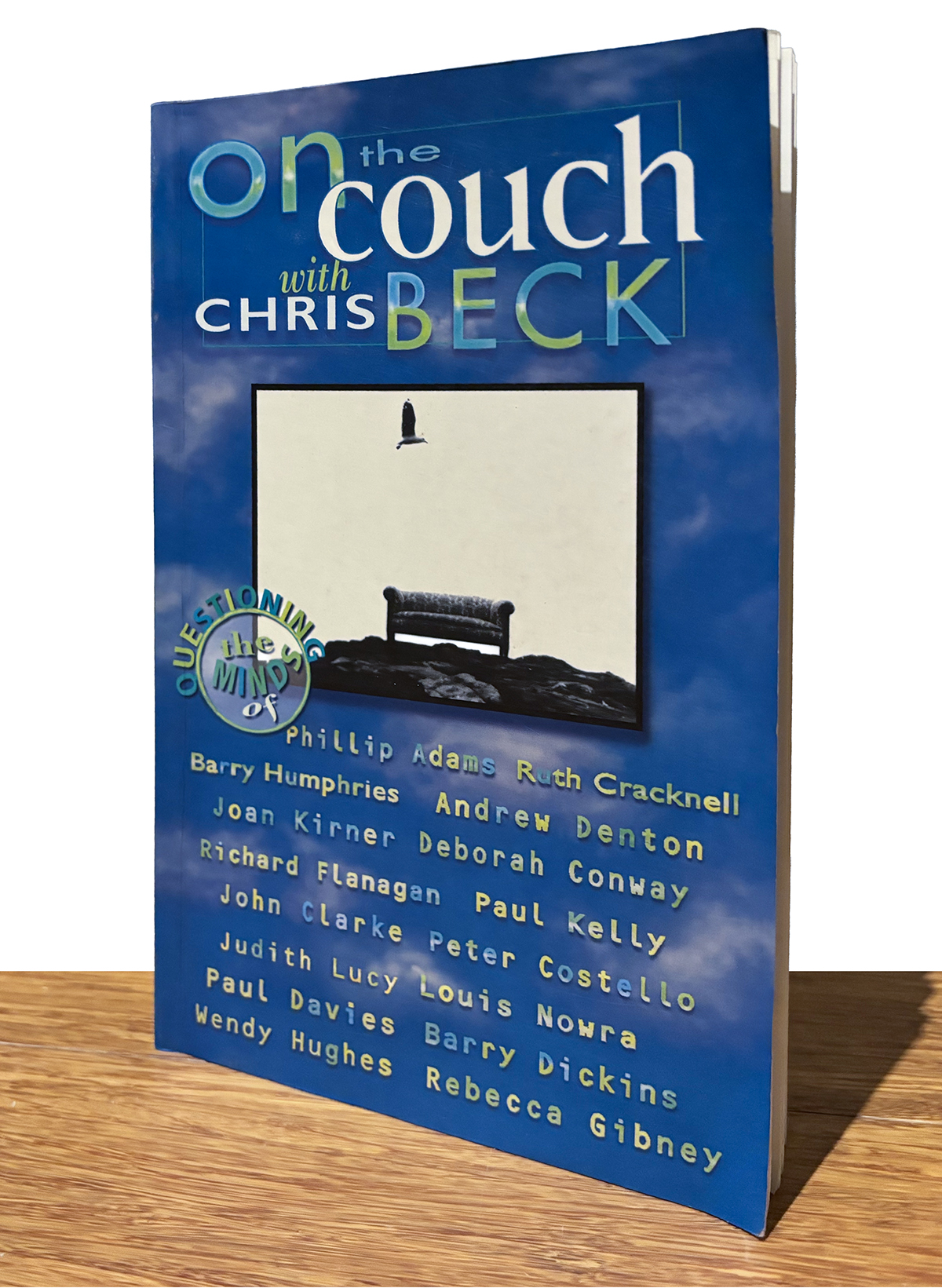

After working with local papers and freelancing briefly in London, I landed a job at the birth of The Sunday Age in late 1989. Soon I was writing stories and taking photos. I came up with column ideas for the ‘EG’ entertainment section that led to ‘On the Couch’ for The Saturday Age, which lasted six years before I pulled the pin. I always believed my idiosyncratic approach to delving into a person’s mind was a combination of my questioning life when mentally wobbly, my mother’s seductive interest in people and my father’s creative philosophy. It wasn’t an intellectual approach but always inquiring as though the interviewee was helping me. The portrait was as important as the interview in revealing the subject.

The series was exhibited at the Centre for Contemporary Photography, Fitzroy, in September 1994.

A book was published by HarperCollins and Andrew Denton, who had told me he read ‘On the Couch’ every week from Sydney, hired me as the writer for the ABC interview series, ‘Enough Rope with Andrew Denton and Elders’ (2003-2010).

In researching Chris’s book one finds, apart from Michael Leunig’s amusing and extended foreword to the book, an uncredited 29 October 1996 review published in Tharunka student magazine, of the then New South Wales University of Technology (now UNSW). That, amongst several reviews appearing at the time, provides the most incisive insight into the approach Beck used for the interviews and photographs it contains:

“Catering to the cult of personality and introduced by Michael Leunig, this book is a surprisingly entertaining compilation of interviews with various celebrities. Chris Beck is a photographer and columnist for The Age, his softly-spoken, inquisitive interview technique a breath of fresh air from the self-gratifying intrusions most pop-culture vultures push. Instead of asking questions that concentrate on the fame and achievements of the interviewee, he uses direct and simple observations to bring-out the motives and philosophy of his subjects.

“Like a psychologist, he lets them ramble on about themselves, directing them with seemingly innocent little questions, encouraging them to open up instead of putting words into their mouth. The focus is always on what makes them tick, not what they’ve done.

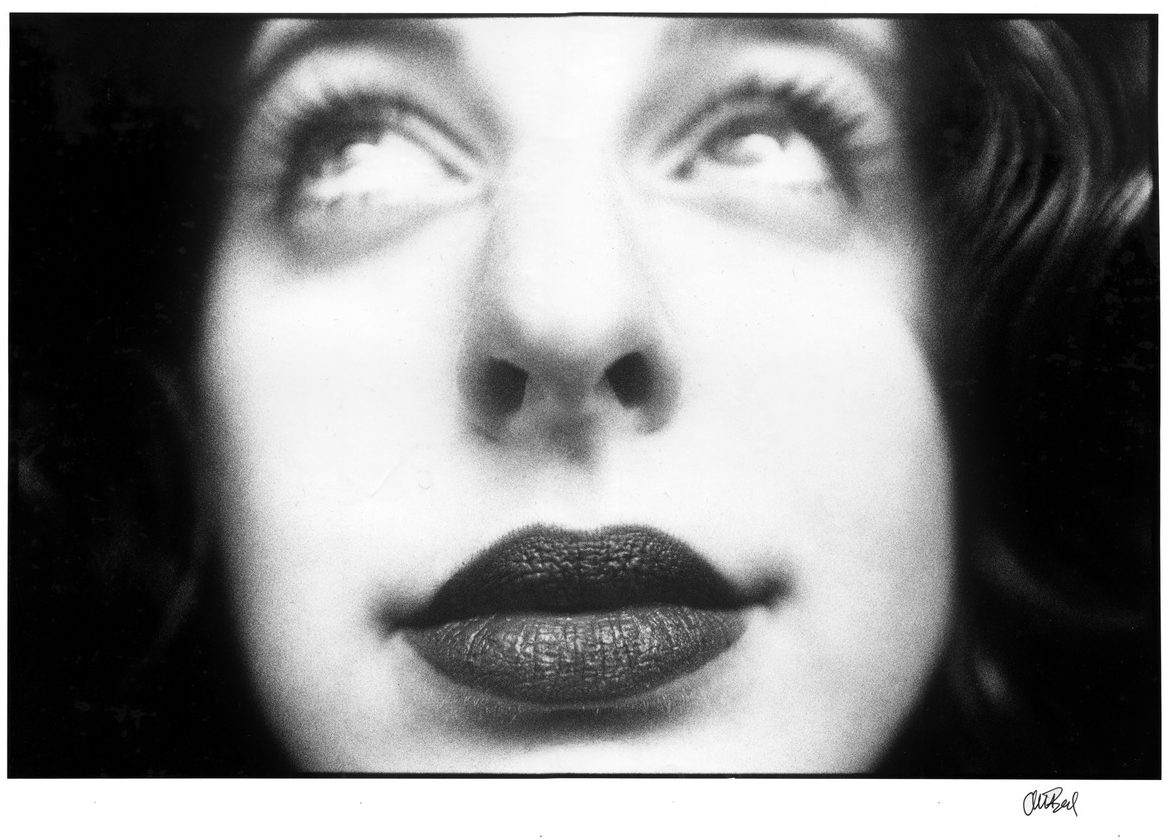

“Amongst the sixty-five characters he investigates in this book are Kate Fischer, Jimeoin, Deborah Conway, Denton, Peter Costello, Poppy King, David Williamson, Ruth Cracknell, Phillip Adams, and Judith Lucy…Egotists, exhibitionists, politicians and people, their souls searched and laid bare before us in soudbite size. The responses and anecdotes he illicits [sic] are frank, honest and more amusing than the usual, Jimeoin talks about having dark thoughts about shooting Ray Martin, Phillip Adams about inserting Logies up Ray Martin’s arse, Kate Fischer says she is proud to be a dumb tit-joke. It’s incredible what prima donnas will say, given a slightly off-beat, receptive listener. Beck’s imaginative black and white portraits also accompany each interview, rounding off a book well worth buying.”

He collaborated with Leunig on another book Dogs and Lovers, published in 2000.

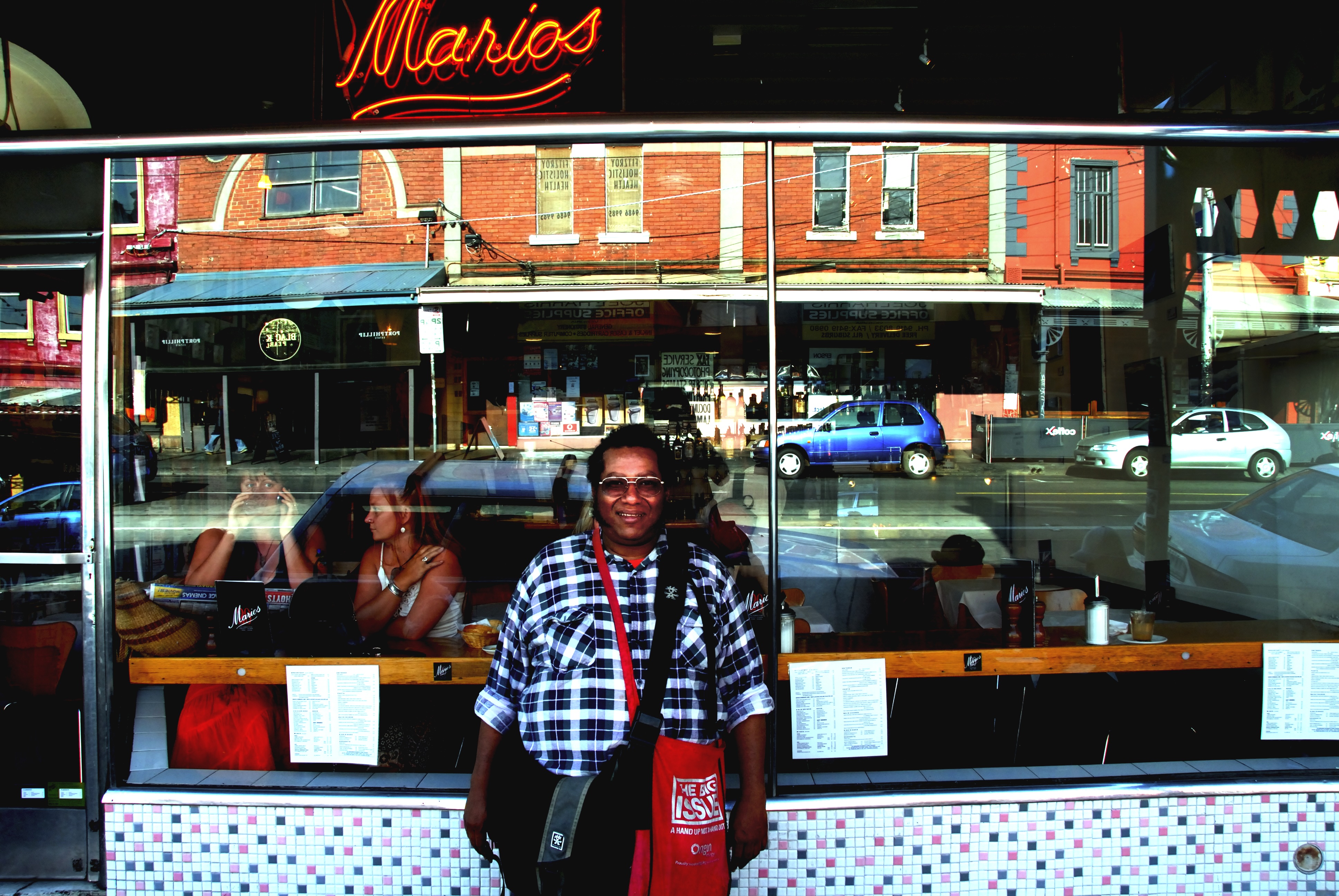

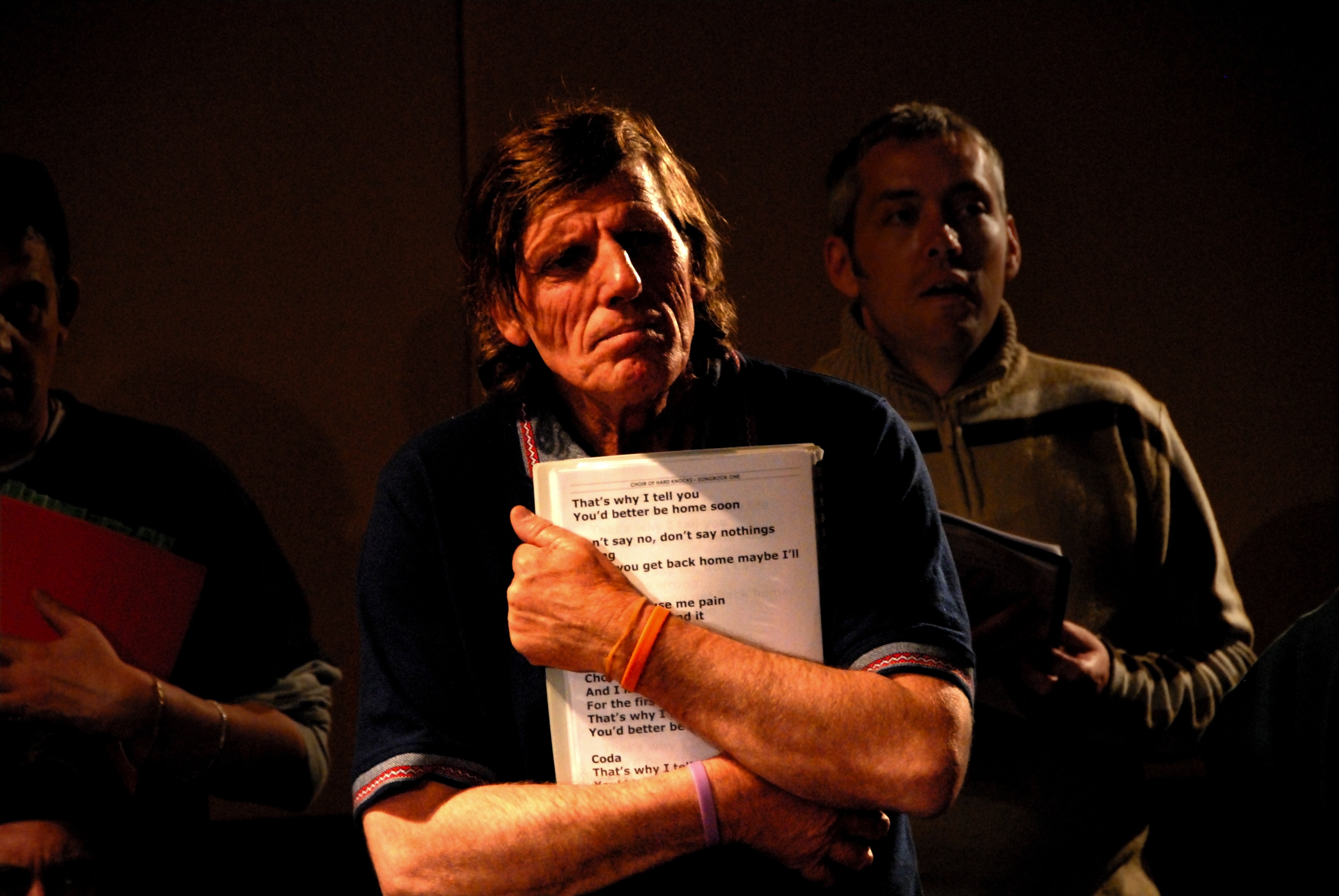

I also produced a photographic book, exhibition and images for the 2007 ABC TV series, following a choir of homeless people around Victoria and ultimately to the Sydney Opera House, which was one of my favourite assignments.

I continued to work in photography, but mostly in combination with writing for publications. I am forever disappointed that my father never saw me recovered mentally and managing to work in the creative industries with some success.

If it hadn’t been for that short time at Prahran College discovering the edifying brilliance of the great photojournalists, I doubt I would have had the privilege of discovering and retelling ideas and concepts about life through researching, talking to and photographing people from all walks of life. Thanks Julie.

Great to read this Chris

LikeLike