Peter Johnson, a food and advertising photographer, was born in 1948 in the north of England and migrated to Australia with his family in the late fifties. He recounts his experience at Prahran College and in a career dedicated to photography.

At the age of twelve, I had saved enough for my first camera, a Brownie Starlett which, though I was not to know at the time, was a purchase that would come to define my life. My love for the fine machinery of photography continued to grow over the years, and upgrading to a new Nikon F reflex camera in the mid-sixties showed me how the camera lens could serve as an extension of my eye.

After graduating from Toowoomba Grammar School, I promptly moved to Brisbane to study architecture at St Lucia (University of Queensland), pursuing a passion that remains to this day. However, finding studies too regimented, I moved on to Sydney where I worked as a junior art director at George Patterson, creators of the iconic VB Big Cold Beer ad. It was this work that introduced me to the idea of photography as more than just an interesting hobby.

Advertising eventually paled, and at the end of 1970, at age 22, I was interviewed by Gordon De Lisle for entry into Prahran College. My experience as an art director, and the publication of several of my black and white images on the back page of The Australian‘s pseudonymous, breezy ‘Martin Collins’ gossip column gained me acceptance into First Year Photography, skipping the orientation year.

My lecturers at Prahran included Paul Cox, Brian Gracey, Derrick Lee, and Athol Smith who, when De Lisle suffered a heart attack, replaced him as head of the department. Among my fellow students were Philip Quirk, Robert Rosen, and Mimmo Cozzolino. Graham Howe was one year ahead. It was an eclectic and interesting mix of students, each with very different approaches to their work.

Like many young students, I was inspired by the work of Magnum’s Cartier Bresson and his documentary photographer colleagues in that famous photo agency, but personally, I was most influenced by American Phil Marco who studied fine art at Pratt Institute and the Art Students League. His work is represented in MoMA. He was described in the New York Times as a minimalist, ‘whose images are sensual, whimsical, often surreal, always strong and deceptively simple.’

Marco’s graphic simplicity aligned with my ‘less is more’ philosophy and my desire to tell stories with the minimum of embroidery. I strived to convey the story with the minimum of elements; It’s what I call ’scrabble photography’ where you have a given number of elements (including the weather and time of day) to make a front cover pic, or double-page chapter opener.

Another strong influence at the time was my experience as a resident of Labassa in North Caulfield, living in Flat 6, which had two rooms; mine was the corner room overlooking the balcony. Spacious and airy, it had a fireplace and four windows. I remember a wonderful, light-filled space that caught the early morning sun; a place where I would lie in bed and study indistinct landscapes on the ceiling.

This was a magical house, one of Melbourne’s grand gold rush mansions that by the seventies was a down-at-heels dowager. Split into high-ceilinged apartments, it was inhabited by a diverse mix of actors, one of whom was Jane Clifton who was then starting her acting career and for whom I made publicity shots. There were filmmakers, musicians, students—including some from Prahran—gays, and film directors – people who had never thought inside the box. It was breeding ground for ideas. In Flat 6 with me was John Kidman with whom I had played in a rock band while at Toowoomba Grammar, he on vocals, me on bass. He was doing his Dip.Ed. at Monash University.

Our spacious bathroom doubled as my dark room with the enlarger on a table opposite the shower, a wooden rack over the bath for developing trays, and the bath itself for a print-wash. The flats weren’t particularly secure and once my enlarger was taken from the unlockable bathroom.

I met Olga Kohut six months after we moved in, and she eventually joined me in the corner room.

motorbike. Photo:

I had always loved to cook, as had Olga, who was of Ukrainian descent, and from her cooking I developed a lifelong love of that food. My own speciality was Spanish and Indian food. We produced wonderful meals from that tiny kitchen, a skinny room next to the upstairs bathroom, fitted with only a gas stove and sink. That was perhaps an early inspiration for my life as a food photographer. The rent was only $16 a week, but we were students, so splitting the rent three ways helped. I worked as a bus driver at night driving a bus from Elsternwick to Princes Bridge, Route 605, then home to Labassa and dinner by 8.30pm. At weekends I worked for a soft drink manufacturer in Footscray.

These excursions gave me a steady stream of portrait (and streetscape) subjects for Prahran’s rolling assignments which were critiqued each Friday afternoon by lecturers and students from all years, providing valuable feedback.

Jane Clifton was someone we saw often, and one College project with her and Simeon Kronenberg (a poet, and later, founding director of Anna Schwartz gallery in Sydney) as models in Judith Cordingley’s flat was titled ‘A Sequence’, and featured them posing for a ‘Victorian’ portrait, first with Simeon in my pinstripe suit, Jane in her vintage dress and fox fur. Over a sequence of ten shots, they gradually swapped clothes and positions; it was almost a story of residents of the house.

It was my love of food that enticed me to specialise in culinary photography. From my earliest memories of helping my Mam knead bread in that distant English kitchen, to growing vegetables for my father’s home-made pickles and chutneys, my world has long revolved around food. It is a passion that has filled both my working and private life, and that continues today.

At the end of my second year at Prahran, I spent some months working for Brian Brandt at his studio in Chapel Street, where I shared the space with Peter Bailey and Rob Imhoff – an exciting and influential time. Ultimately, Europe and travel called. I spent over a year working in London and Exeter before moving to Denmark to the largest and best-equipped studio I had yet experienced. I travelled frequently in that time, to places like Spain, France, and Morocco, where I ate and enjoyed the local cuisines, always learning and shooting on 35mm.

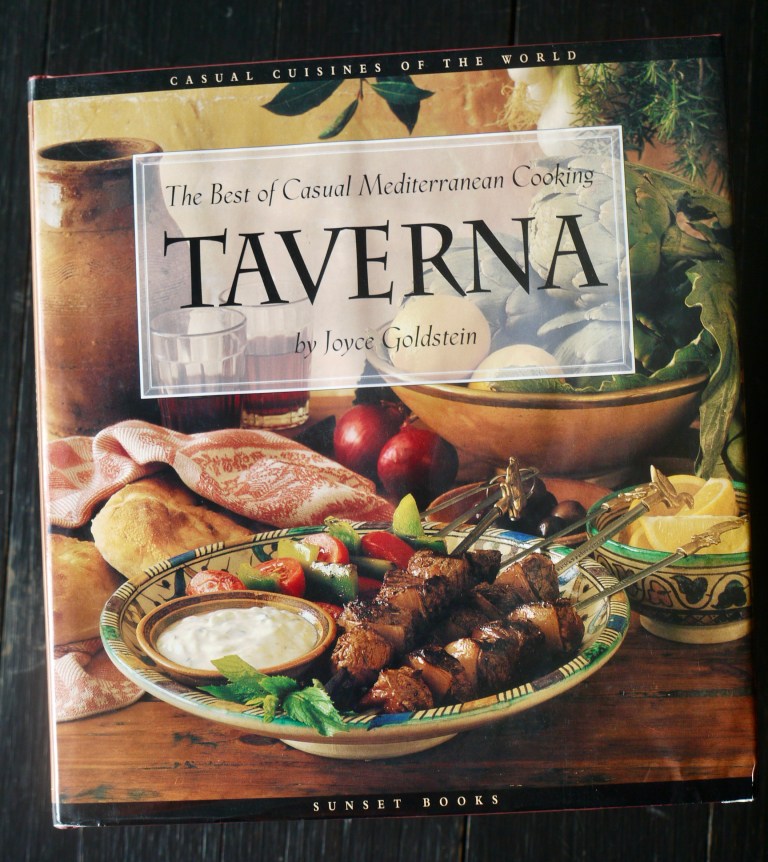

On returning to Australia, I established my own studio in Sydney and within my first year won the Hasselblad Masters Award. In subsequent years, my work has appeared in just about every major lifestyle publication in Australia, including Belle, Gourmet Traveller, Vogue Entertaining, Harper’s Bazaar and Good Weekend, as well as in advertising campaigns and high-end cookbooks, many of which were commissioned by American publishers and sold around the world.

My reputation was clearly established by 1985 when I was described by Elisabeth King in the Sydney Morning Herald (27 August 1985) as ‘one of Sydney’s top food photographers’ in an article on the outfits worn Sydney chefs when they were cooking, and she for some reason saw fit to interview me amongst them.

In 1986 I worked with Gretta Anna and her husband Dr David Teplitzky on her second cookbook. For her first, published in 1979, they had approached a number of publishers and they all said that hardcover cookbooks without photos on the front cover sell 2,000-3,000 copies at the most. Nevertheless, the Teplitzkys decided to finance the book themselves and since then it has been reprinted more than 13 times had sold around 100,000 copies.

For the new book, published in 1987, Gretta, always fastidious, cooked her homegrown recipes for all my photographs herself and I assisted with coordinating the elegantly simple styling, for which white crockery was used throughout and shot from overhead with broad-source light and presented on a white marble background.

Gretta Anna Teplitzky, Tessa Schneideman (1987) More Gretta Anna recipes. 1st ed. Quando, Sydney, ISBN:9780908435012

When in 1991 Italy: A Culinary Journey was published, Sheridan Rogers wrote in Good Weekend (28 September, p.56) that;

‘…browsing through Italy: A Culinary Journey…I felt as though I were back there. The photos of both food and country evoke the smells and tastes, the earthy guts at the heart of Italian cooking…and one of Australia’s leading food photography teams (Peter Johnson and Janice Baker) worked on the food shots. They are simple and elegant…’

In America the book collected an Award for Illustrated Photography from the International Association of Culinary Professionals in 1992.

Subsequent books also featured Italian food but also the traditional cuisines of other countries on the Mediterranean, of France and Asia, and eventually Australia.

I have been voted Australian Food Photographer of the Year and won numerous awards, including the coveted James Beard Award for the best cookbook photography, and the highly prestigious Julia Childs Award, for which I was nominated three times and won twice.

One of the highlights of my food-focused career was working with Richard Olney, an American food writer, painter, cook, author, and editor, who lived in France for fifty years and was highly lauded by French food and wine societies. Describing his experience of working with me, he wrote:

‘I was impressed… by the layout, the quality of the photos, and the presentation of the food, which always looked right.’ Kind words from a rigorous perfectionist.’

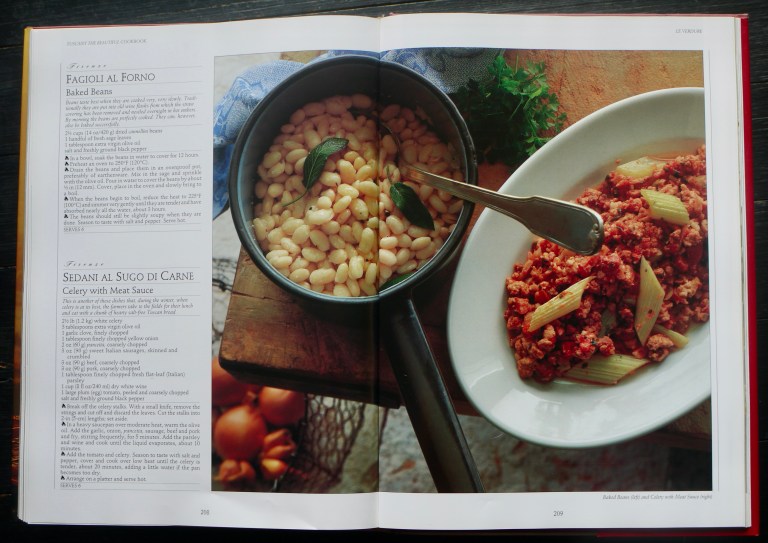

The work behind culinary photographing is not always appreciated and sometimes not well received, as in Rita Erlich’s discussion in The Age, 23 March 1993 of the cookbook Tuscany the Beautiful for which I teamed with Janice Baker, a food stylist whom I often called on:

‘It’s sometimes hard to know who is responsible for these books. The best cookbooks are clearly a cooperative venture between writer, photographer, and designer. There’s a food stylist and an editor in that team, too, but their efforts are usually not so immediately obvious. (And if you look at the acknowledgements, you find a list of people that makes each book sound as big as a Broadway production.) In ‘Tuscany the Beautiful’, I felt that the members of the team were sometimes working independently of the others. The text and recipes are Lorenza de’ Medici’s, the food photography is by Peter Johnson, the food styling by Janice Baker…Some of the dishes are shown in extreme close-up, from above, so they are life-size (and seem larger than life). It’s disconcerting because we don’t see food ilke that: our own field of vision takes in more than a plate or two with the inevitable cloth or napkin and some vegetables. But at least you know how it’s meant to look. Or do you? There’s a recipe for fagioli al forno, the Tuscan version of baked beans. It’s a simple dish, very Tuscan, and the recipe calls for an ovenproof pot “preferably earthenware” and ends with the note that “the beans should still be slightly soupy when they are done.” What we are shown on the same page is a saucepan (apparently enamelled) filled with beans that look well-drained and not at all long-cooked – certainly not soupy. On the other hand, slightly soupy beans in an earthenware pot do not photograph appetisingly. And since the aim is to make the food attractive, I suppose there must be some licence.’

Erlich goes on to more fulsome praise for The de’ Medici Kitchen;

‘Photography by Peter Johnson and styling by Janice Baker are also on show in The de’ Medici Kitchen, the book of the television series. It’s a smaller format book, which means the chances are higher that someone will actually take it into the kitchen. The pages are glossy, and the paper is marbled, which makes it all seem very luxurious.’

Leo Schofield had no such qualms about the Tuscany book in his SMH column Short Black of 27 April 1993 when he announced;

‘As a glance at any issue of Gourmet Traveller or Vogue Entertaining Guide will confirm, Australian food photography is the finest in the world. And an Australian, Peter Johnson, is rated tops in this field. For his work on France: The Culinary Journey, Johnson has just taken out the prestigious International Association of Culinary Professionals Award in New Orleans. He’s also up for the James Beard Best Food Photography award on May 3 in New York. Of the three finalists, two are his, the aforementioned book and Tuscany the Beautiful, so he’s odds-on favourite. Johnson is also in charge of the pictures for a new glossy work on Australian food with text by Cherry (Goodbye Culinary Cringe) Ripe and recipes from Elise Pascoe, due out in August next year.’

In a subsequent issue confirming Johnson’s success in the James Beard, Schofield tried to dodge accusations of sexism when he belatedly acknowledged that behind Peter was “Janice Baker, without whom those seductive images would not have been possible. She has been Peter’s partner and stylist on most of his assignments.”

1992 was a great year of both of them; they jointly won the 1992 Julia Child Award for Best Illustrated/Photographed Cookbook, and again he was shortlisted for that prize in 1994 with his photography for Richard Olney’s Provence the Beautiful Cookbook.

Susan Parsons of The Canberra Times, in her 23 November 1994 review of Ian Parmenter’s Consuming Passions – The Complete Collection, described me as ‘Australia’s most celebrated food photographer’ and earlier, when reviewing Italy a Culinary Journey in the same newspaper on 22 October 1991 praised the ‘mouth-watering colour photographs taken in Australia by Peter Johnson.’

Reviewing the new edition of the Australia the Beautiful Cookbook, Erlich reiterates her preference for food shot in situ, but with new appreciation of the ‘food photography by the marvellous Peter Johnson’;

‘The food photography is softly lit and attractive. It tends to make most sense when placed in a setting – steamed chilli mussels are [sic] chilli fish stir-fry are more obviously Australian when photographed at Cremorne Point.’ [Rita Erlich, ‘Australia, she’s a beautiful meal. The Age 24 Oct. 1995, p. 37.]

That book continued to draw attention. Roslyn Grundy in her ‘Epicure’ column in The Age noted that at the Australian Food Writers’ Awards of 1997 Janice and I had won best food stylist/best food photographer with our pavlova photograph in the Australia the Beautiful Cookbook.

In 1997, to coincide with Melbourne Food Week, I joined seventeen other acclaimed food photographers in Melbourne See Food, a joint exhibition at the RMIT Gallery. The curator of that exhibition, Linda Williams, admired ‘the sparse yet very effective compositions’ of my work, and went on to say that my;

‘…photo of white asparagus has an inchoate connection to the simplicity of seventeenth-century Spanish bodegóns, but the references to older cultural traditions are suggestive because they are oblique.’

I loved working with natural light and devised several home-made cutters and shadow-makers to take with me every location shoot to modulate available light, and I could replicate the same in my studio. A client had only to tell me where, what time of day, and the season and I could recreate it.

When judging my own work, I had one yardstick: ‘If you wanted to lick the page, then I had succeeded in sharing the sensuality of food.’

Peter was always a leader in the food photography field, greatly respected and always ready to lend a hand to “a struggling assistant with high aspirations”. Peter was the first photographer I met when I returned to Australia after being a freelance photographic assistant in Europe for 3 years. His advice was greatly appreciated when starting my career. I will always thank him for that – he has remained a friend since.

Peter’s affinity with food shines through in his work in a career that spanned many decades.

LikeLike